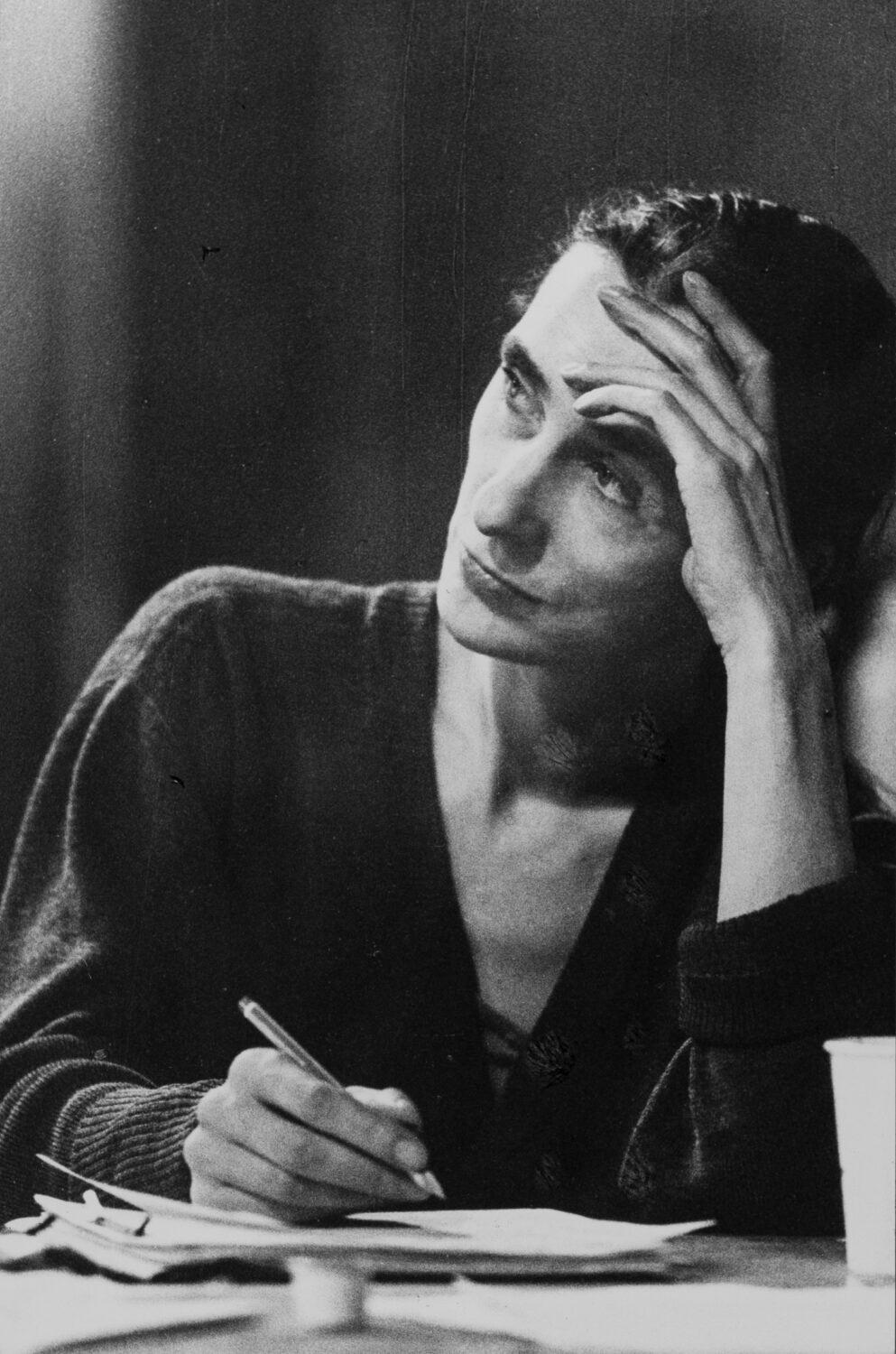

What moves me

In 2007, Pina Bausch was awarded the Kyoto Prize. The Kyoto Prize is awarded annually by the Inamori Foundation. Internationally, it is recognized as the most important prize within the cultural field.

Pina Bausch rarely spoke about her work. However, at the award ceremony in Kyoto, Pina Bausch had to give a speech. She spoke about her work and her experiences as a dancer and choreographer in her own words. That is what makes this speech very special.

Published with the kind permission of the Inamori Foundation.

When I look back on my childhood, my youth, my period as a student and my time as a dancer and choreographer – then I see pictures. They are full of sounds, full of aroma. And of course full of people who have been and are part of my life. These picture memories from the past keep coming back and searching for a place. Much of what I experienced as a child takes place again much later on the stage.

Let me begin then with my childhood.

The war experiences are unforgettable. Solingen suffered a tremendous amount of destruction. When the air raid sirens went off, we had to go into the small shelter in our garden. Once a bomb fell on part of the house as well. However, we all remained unharmed. For a time, my parents sent me to my aunt’s in Wuppertal because there was a larger shelter there. She thought I would be safer there. I had a small black rucksack with white polka dots, with a doll peering out of it. It was always there packed ready so that I could take it with me when the air raid siren sounded.

I remember too our courtyard behind the house. There was a water pump there, the only one in our area. People were always lining up there to fetch water.

This was because people had nothing to eat; they had to go bartering for food. They would swap goods for something to eat. My father, for example, swapped two quilts, a radio, and a pair of boots for a sheep so we would have milk. This sheep was then covered – and my parents called the baby lamb “Pina.” Sweet little Pina. One day it must have been Easter “Pina” lay on the table as a roast. The little lamb had been slaughtered. It was a shock for me. Since then I haven’t eaten any lamb.

My parents had a small hotel with a restaurant in Solingen. Just like my brothers and sisters, I had to help out there. I used to spend hours peeling potatoes, cleaning the stairs, tidying rooms – all the jobs that you have to do in a hotel. But, above all, as a small child I used to be hopping and dancing around in these rooms. The guests would see that too. Members of the chorus from the nearby theatre regularly came to eat in our restaurant. They always used to say: “Pina really must go to children’s ballet group.” And then one day they took me along to the children’s ballet in the theatre. I was five at the time.

Right at the very beginning, I had an experience I shall never forget: all the children had to lie on their stomachs and lift up their feet and legs, bending them forwards and placing them to the right and left of their heads. Not all the children were able to do this, but for me it was no problem at all. And the teacher said at the time: “You’re a real contortionist.” Of course I didn’t know what that meant. Yet I knew from the intonation, how she had said the sentence, that it must be something special. From then on, that was where I always wanted to go.

There was a garden behind our house, not very large. That’s where the family shelter was and a long building – the skittle alley. Behind it was what used to be a gardening centre. My parents had bought this plot of land in order to open up a garden restaurant. They started off with a round dance floor made of concrete. Unfortunately nothing came of the rest. But for me and all the children in the neighbourhood it was a paradise. Everything grew wild there, between grasses and weeds there were suddenly beautiful flowers. In summer we were able to sit on the hot?tarred roof of the skittle alley and eat the dark sour cherries that hung over the roof. Old couches on which we were able to jump up and down as if on a trampoline. There was a rusty old greenhouse; perhaps that’s where my first productions began. We played zoo. Some children had to be animals, the others visitors. Of course, we made use of the dance floor. We used to play as if we would be famous actors. I was usually Marika Röck. My mother didn’t like all this at all. Whenever she came, someone would make a sign and everybody would hide.

Because there was a factory nearby that made chocolate and sweets, we children would always stand on the drains from which the warm and sweet vapours were coming. We didn’t have any money, but we could smell.

Even the restaurant in our hotel was highly interesting for me. My parents had to work a great deal and weren’t able to look after me. In the evenings, when I was actually supposed to go to bed, I would hide under the tables and simply stay there. I found what I saw and heard very exciting: friendship, love, and quarrels – simply everything that you can experience in a local restaurant like this. I think this stimulated my imagination a great deal. I have always been a spectator. Talkative, I certainly wasn’t. I was more silent.

My first time on the stage, I was five or six. It was in a ballet evening – the sultan’s harem and his favourite wives. The sultan lay on a divan with many exotic fruits. I was made up and dressed as a Moor and had to spend the whole performance wafting air towards him with a great fan. Another time in “Mask in Blue,” an operetta, I had to play a newspaper boy. Crying the whole time: “Gazzetta San Remo, Gazzetta San Remo, Armando Cellini wins prize.” I took great pleasure in doing everything very precisely. I took the daily newspaper “Solinger Tageblatt,” pasted over the title and wrote “Gazzetta San Remo” very carefully on each individual newspaper. Admittedly, nobody could see it, but for me it was very important. I was allowed to play in many operas, operettas, dance evenings, and ultimately even in the dance evenings as part of the group. One thing was always clear for me; I didn’t want to do anything other than be involved in the theatre. Nothing else but dance.

In the children’s ballet group there was once a situation when we were supposed to do something that I didn’t understand at all. I was desperate and embarrassed and I refused to try it. I simply said: “I can’t do it.” After that, the teacher sent me straight home. I suffered for weeks; I didn’t know what I should do to get back there. Weeks later, the teacher came to our home and asked why I had stopped coming. From then on I started going again of course. But that sentence, “I can’t do it,” is something I’ve never said again.

The presents from my mother were sometimes embarrassing. She went to a tremendous amount of effort to find special things for me. For example, at the age of 12 I received a large fur coat – I had the first pair of long, checked trousers that appeared in the shops – I was given green, square shoes. But I didn’t want to wear any of this. I wanted to be inconspicuous.

My father was a great figure of a man with a good sense of humour and lots of patience. He had a wonderfully loud whistle. As a child, I always loved sitting on his lap. He had unusually large feet – size 50. His shoes had to be made especially for him. And my feet were getting bigger and bigger too. When I was twelve, I had size 42. I became scared that they might grow even more so that I wouldn’t be able to dance any longer. I prayed: “Dear God, please don’t let my feet grow any more.”

Once my father became very ill and had to take a rest cure. I was 12 years old. Two neighbours looked after me, and I managed the pub all on my own. For two weeks I took care of the pub all alone, pulled the beers and looked after the guests. I learnt a great deal while doing it. I found this very important and also very pleasant. In any case, I wouldn’t have exchanged the experience for anything.

I used to love doing homework. It was a tremendous pleasure, maths exercises in particular. Not so much the exercises themselves, but writing them and then seeing what the page looked like.

When Easter came, we children had to look for Easter eggs. My mother came up with hiding places that took me days to find. I loved searching and finding. When I’d found them, I wanted her to hide the eggs again.

My mother loved walking barefoot in the snow. And also having snowball fights with me, or building igloos. She also liked climbing trees. And she was tremendously frightened during thunderstorms. She would hide in the wardrobe behind the coats.

My mother’s travel plans were always surprising. There was one occasion, for example, when she wanted to go to Scotland Yard. My father loved fulfilling all my mother’s wishes whatever they were – so then they actually did go to London.

There’s a photo with my father sitting on a camel. However, I can’t remember any more which country the two of them were in…

Although my mother knew nothing about technical matters, she always astonished me. There was one time when she took a broken radio completely apart, repaired it and then somehow put it together again.

Before my father bought the small hotel with the restaurant in Solingen, he was a long-distance truck driver. He came from a rather humble family in the Taunus Mountains and had a lot of sisters. In the beginning he had a horse and cart for transporting goods. Later he bought a lorry and he then drove all over Germany in it. He loved talking about his travels and then singing a special lorry driver’s song with its many, many verses at the top of his voice.

Not once in his whole life did my father tell me off. There was only one time, when it was very serious, then he didn’t call me Pina, but Philippine, my real name. My father was someone you could depend on absolutely.

My parents were very proud of me although they almost never saw me dance. They were never particularly interested in it either. But I felt myself greatly loved by them. I didn’t have to prove anything. They trusted me; they never blamed me for anything. I never had to feel guilty, not even later on. It is the most beautiful gift they could have given me.

At the age of 14, I went to Essen to study dance at the Folkwang School. The important thing for me there was meeting Kurt Jooss. He was a co-founder of this school and one of the very great choreographers.

The Folkwang School was a place where all the arts were gathered under one roof. It not only had the performing arts such as opera, drama, music and dance but also painting, sculpture, photography, graphics, design and so on. There were exceptional teachers in all departments. In the corridors and the classrooms there were notes and melodies and texts to be heard, it smelled of paint and other materials. Every corner was always full of students practising. And we visited each other in the different departments. Everybody was interested in everybody else’s work. In this way many joint projects came into being as well. It was a very important time for me.

Kurt Jooss had outstanding teachers in his department. He also brought in teachers and choreographers to Essen whom he regarded highly, especially those from America, and they would teach courses or stay in Essen for longer periods of time. I learnt a great deal from them.

In any case a very important part of the training was to have a foundation – a broad base – and then after working for a lengthy period of time, you had to find out for yourself, what have I to express. What have I got to say? In which direction do I need to develop further? Perhaps this is where the foundation stone for my later work was laid.

Jooss himself was something special for me. He had a lot of warmth and humour and an incredible knowledge in every possible field. It was through him, for example, that I first really came into contact with music at all, because I only knew the pop songs from our restaurant, which I had heard on the radio. He became like a second father. His humanity and his vision, those were the most important things for me. What a stroke of luck it was meeting him at such a crucial age.

During my studies there was a time when I had terrible back pain. I had to visit lots of doctors. The result was that I was supposed to stop dancing immediately, otherwise I would be put on crutches in six months. What was I to do? I decided to keep dancing even if it was only to be for half a year. I had to decide what was really important for me.

In 1958 I was nominated for the Folkwang performance award. To do this, I had to make my own small programme. The day of the presentation came. I had to go on stage. I got into position, the light went on – and nothing at all happened. The pianist wasn’t there. Great excitement in the hall, and the pianist was nowhere to be seen. I stayed on the stage, still standing in my pose. I became calmer and calmer and simply kept standing. I can’t remember any more how long it went on for. But it was quite a long time till they had found the pianist. He was somewhere completely different, in another building. In the hall, people were astounded that I had remained standing there in that pose for so long with such conviction and tranquillity. I grew and grew. When the music started, I began my dance. By that time I had already realized that in extremely difficult situations a great calm overcame me, and I could draw power from the difficulties. An ability in which I have learnt to trust.

I was ravenous to learn and to dance. That is why I applied for a scholarship from the German academic exchange service for the USA. And I did in fact receive it. Only then did it become clear what that meant: travelling by ship to America, aged 18 years, all alone, without being able to speak a word of English. My parents took me to Cuxhaven. A brass band was playing as the ship was setting off and everybody was crying. Then I went onto the ship and waved. My parents were also waving and crying. And I was standing on the deck and crying too; it was terrible. I had the feeling we would never see each other again.

I then wrote another short letter to Lucas Hoving in New York and posted it in Le Havre. He had been one of the lecturers in Essen. I was hoping that he would pick me up in New York. Eight days later, when I arrived in New York, I didn’t have my health certificate in my bag but in my suitcase. I therefore had to spend many hours on the ship waiting until the 1,300 passengers had been dealt with. Then they took me to my suitcase. I no longer believed that Lucas Hoving would still be there, even if he had received my letter at all. Yet when I walked off the ship, he was actually standing there. And hanging over his arm were some flowers that had wilted because it was so hot. He had been waiting for me all that time.

In the beginning, life in New York wasn’t easy because I couldn’t speak any English. When I wanted to eat, I went into a cafeteria where I could simply point directly at what I wanted to have. Once, when I wanted to pay, I couldn’t find my purse. It was gone. What was I supposed to do, how was I going to pay? A terribly embarrassing situation. After some time, I then went to the cash desk and tried to explain that my purse had gone. Then I took my point shoes and my other shoes out of my bag, laid everything on the counter and explained that I would leave everything there and return. The man at the cash desk simply gave me five dollars so that I would be able to travel home. I found it incredible that he trusted me so much. I then kept going back to this cafeteria, just to smile at the man. I often experienced situations like this in New York; the people were so ready to help.

In New York I took on everything, which was offered to me. I wanted to learn everything and experience everything. It was the great period of dance in America: with Georg Balanchine, Martha Graham, José Limón, Merce Cunningham... In the Juilliard School of Music, where I studied, there were teachers like Antony Tudor, José Limón, dancers from the Graham Company, Alfredo Corvino, Margarete Craske – I also did an unbelievable amount of work with Paul Taylor, Paul Sanasardo and Donya Feuer.

Almost every day I watched performances. There were so many things, all of them important and unique; therefore I decided to stay two years on the money that was only intended for one. That meant saving! I walked everywhere. For a time I live almost exclusively on ice cream – nut flavoured ice cream. Accompanying this was a bottle of buttermilk, a lot of lemon that was lying around on the tables and a large amount of sugar. All mixed together, it tasted very good. It was a wonderful main meal.

However, I liked getting thinner. I paid more and more attention to the voice within me. To my movement. I had the feeling that something was becoming purer and purer, deeper and deeper. Perhaps it was all in the mind. But a transformation was taking place. Not only with my body.

During the second year in New York, I was lucky to be hired by Antony Tudor, who was Artistic Director at the Metropolitan Opera at the time. The Met was another important experience. It was the time when Callas had unfortunately just left. But you could still sense her. Apart from the fact that I was dancing a lot, I was also watching plenty of operas or would hear the singers in the changing room over the loudspeakers. What a joy it is to learn to distinguish between voices. To listen very exactly.

And then there was another very special experience. When I flew back from my stay in Europe to come to the Met, the plane was overbooked. I was one of the passengers who weren’t able to fly. In New York, I had an appointment with a lawyer who was intending to insert something into my passport so that I would be allowed to work at the Met. Consequently, I had to get to New York no matter what. And then, instead of waiting, I took a flight to New York via a roundabout route. I had to change flights five times or more. It was madness: one flight to Toronto, then one to Chicago, and so it went on to yet another place – and it was all highly complicated. But I managed it somehow. The flight took a very long time. Finally, I arrived in New York, but at a different airport. I have no idea how – but somehow I also managed with my broken English to arrange for someone to fly me by helicopter to the right airport. And they did actually do it. I had succeeded. After this flight, you could have sent me anywhere on earth. I had no more fear. Of course my luggage was no longer there. I received it 14 days later. And so I arrived with only my handbag.

All of these actions were unexpected. Nothing was planned. I had no idea that I could act in this way. That I was capable of doing that. Even less so, that I could appear on the stage like that. It just happened – without thinking. You do something without imagining or wishing. It is something different.

After two years came a phone call from Kurt Jooss. He had the chance again to have another small ensemble at the school, the Folkwang Ballet. He needed me and asked me to come back. At the time I was wrestling with a great conflict between the desire to stay on in America, and the dream of being allowed to dance in Jooss’s choreographies. I wanted both of these things so much. I loved it so much being in New York; everything was going wonderfully well for me. However, I returned to Essen after all.

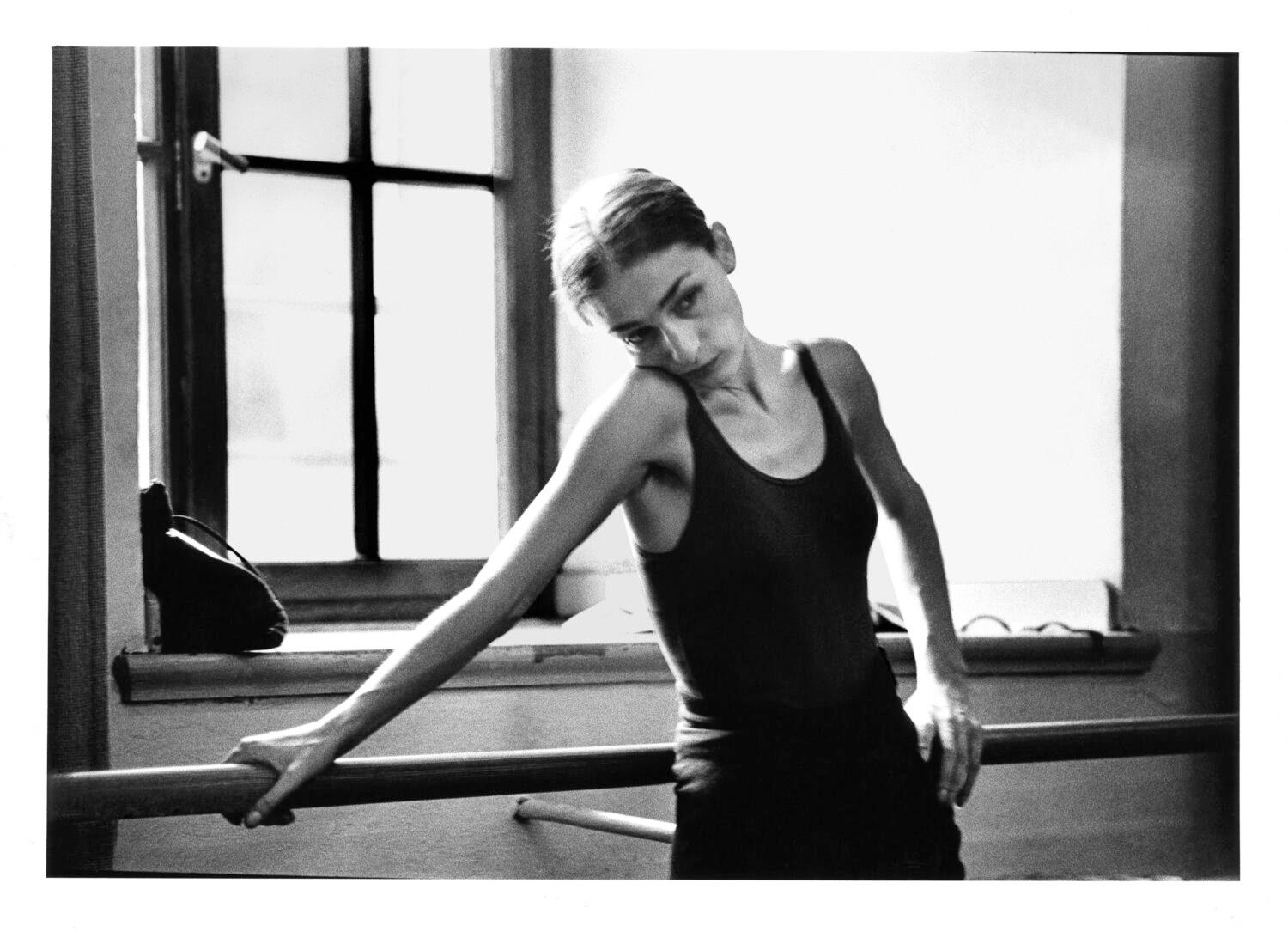

Jooss now had a company again – the Folkwang Ballet. I continued working with wonderful teachers and choreographers. Jooss placed so much trust and responsibility in me, not only by letting me dance in his old and new choreographies, but also by allowing me to help him. However, I didn’t feel fulfilled. I was hungry to dance a lot and had the urge to express myself… So I started to choreograph my own pieces.

Once Jooss came into the rehearsal and watched and said: “Pina, what are you doing, crawling around on the ground all the time?” To express what really lay in my heart, it was impossible for me to use other people’s material and forms of movement. Simply out of respect. What I had seen and learnt was taboo for me. I put myself in the difficult situation: why and how can I express something?

When Jooss left Essen, I took over the responsibility for what had become known as the Folkwang Tanzstudio. The work and the responsibility were very fulfilling for me. I was trying to organize guest performances abroad. Choreographing small pieces. Twice I was also invited to do something in Wuppertal.

And then Arno Wüstenhöfer, general director of the Wuppertal Bühnen, asked me to take over the Wuppertal Ballet as director. I never actually wanted to work in a theatre. I didn’t have the confidence to do it. I was very frightened. I loved working freely. But he wouldn’t give up and kept asking me until I finally said: “I can give it a try.”

Then, at the beginning – I did in fact have a large group and in the rehearsals I was afraid to say, “I don’t know,” or “let me see.” I wanted to say, “OK, we’ll do this and this.” I planned everything very meticulously but soon realized that, apart from this planned work; I was also interested by completely different things that had nothing to do with my plans. Little by little I knew… that I had to decide: do I follow a plan or do I get involved with something which I don’t know where it will take me. In Fritz, my first piece, I was still following a plan. Then I gave up planning. Since that time, I have been getting involved in things without knowing where they will lead.

Actually, the whole time I only wanted to dance. I had to dance, simply had to dance. That was the language with which I was able to express myself. Even in my first choreographed pieces in Wuppertal, I was thinking of course that I would be dancing the role of the victim in Sacre and in Iphigenie the part of Iphigenie, for example. These roles were all written with my body. But the responsibility as choreographer had always held back the urge to dance. And this is how it came that I actually have passed on to others this love, which I have inside me, this great desire to dance.

For the audience our new start was a big change. My predecessor in Wuppertal had done classical ballet and was very much loved by the public. A certain type of aesthetic was expected; there was no disputing that there were other forms of beauty apart from this.

The first years were very difficult. Again and again spectators would leave the auditorium slamming doors, while others whistled or booed. Sometimes we had telephone calls in the rehearsal room with bad wishes. During one piece I went into the auditorium with four people to protect me. I was scared. One newspaper wrote in its review: “The music is very beautiful. You can simply shut your eyes.” The orchestra and chorus also made things very difficult for me. I wanted so much to develop something with the chorus. They turned down every idea. In the end I managed to have the chorus singing from the boxes – from amongst the audience – that was then very nice.

When we did a Brecht-Weill evening, some of the musicians from the orchestra said, “But that’s not music.” They simply thought that I was young, inexperienced – that you could do anything with me. That hurt a lot. But all of this couldn’t stop me trying something, which was important to me, to express as well as possible. I never wanted to provoke. Actually, I only tried to speak about us.

The dancers were full of pride as they accompanied me on this difficult path. But sometimes there were enormous difficulties as well. Sometimes I succeeded in creating scenes where I was happy that there were images like this. But some dancers were shocked. The shouted and moaned at me. Saying what I was doing was impossible.

When we did Sacre – it calls for a large orchestra – the musicians couldn’t fit into our orchestra pit. We therefore did Sacre with a tape recording. With a wonderful version by Pierre Boulez.

In Bluebeard I was unable to put my idea into practice at all because they provided me with a singer who, although I liked him very much in all other respects, was not a Bluebeard at all. In my desperation I thought up a completely different idea with Rolf Borzik. We designed a sort of carriage with a tape recorder that was fastened to the ceiling of the room with a long cable. Bluebeard could now push this carriage and run along with it wherever he wanted. He was able to rewind the music and repeat individual sentences. In this way he was able to wind forwards and backwards to examine his life.

To avoid the problems with chorus and orchestra, in the next piece, Come Dance With Me, I exclusively used beautiful old folk songs, which each dancer sang them – accompanied only by a lute.

In the next piece, Renate Emigrates, there was only music from tape, and only one scene in which our old pianist played in the background. In this way a completely different new world of music opened up.

Since then, the entire wealth of different types of music from so many different countries and cultures has become a fixed component of our work. But also now the collaboration with orchestra and choir – such as in revivals – arouses a great curiosity in everyone and a desire for new opportunities.

New was also the way of working with ‘questions.’ Even in Bluebeard I had started to pose questions for some roles. Later in the Macbeth piece He Takes Her by the Hand and Leads Her into the Castle, the Others Follow, in Bochum; I then developed this way of working further. There were four dancers, four actors, one singer…and a confectioner. Here of course I couldn’t come up with a movement phrase but had to start somewhere else. So I asked them the questions, which I had asked myself. That way, a way of working originated from a necessity. The “questions” are there for approaching a topic quite carefully. It’s a very open way of working but again a very precise one. It leads me to many things, which alone, I wouldn’t have thought about.

The first years were very difficult for me. That hurt too. But I’m not a person who simply gives up. I don’t run away when a situation is difficult. I have always kept on working. I couldn’t do it differently. I continued trying to say and do something, which I thought I had to do.

One person particularly helped me in this: Rolf Borzik. Orpheus and Eurydice was our first joint work in Wuppertal. Rolf Borzik and I not only worked together but also lived together. We got to know each other during our studies at the Folkwang School in Essen. He studied graphic arts. He was an ingenious draughtsman, but also a photographer and painter. And even during his time as a student, he came up with every possible invention. For instance, he developed a bicycle with which you could ride on water and which always ended up collapsing. He was interested in all sorts of technical things, the development of aircraft or ships. He was an incredibly creative person. He never thought that he would become a set designer. Just like I never thought I would become a choreographer. I only wanted to dance. It simply happened that way for both of us.

The collaboration was very intense. We were a source of mutual inspiration for each other. We had thousands of ideas for each piece, came up with many drafts. We could rely on each other in all questions, attempts, uncertainties, even doubts during the process of creating a new piece. Rolf Borzik was always there during all the rehearsals. He was always there. He always supported and protected me. And his imagination was boundless.

For The Seven Deadly Sins he went with some stage technicians out of the theatre and into the city, where they made a casting of one of the streets, to bring the street in real on stage. He was the first set designer to bring nature onto the stage – soil covered the floor of the stage in The Rite of Spring; leaves for Bluebeard, undergrowth and brushwood for Come Dance With Me and finally water for Arien – all pieces from the seventies. They were bold and beautiful designs. Also the animals that appeared on the stage were his inventions – the hippopotamus, the crocodiles. And the first thing you could always hear in the theatre workshops was: “There’s no way you can do that.” But Rolf Borzik always knew how to do it. He made everything possible. He once called his stage “free action rooms,” and he said, “Which make us into happy and cruel children.” He worshipped and loved all the dancers very much. His photos of rehearsals and performances are very close, very tender. Nobody was able to see like that.

He did his last set for the piece Legend of Chastity. By then we had known for some time that he didn’t have much longer to live. Yet this Legend of Chastity is not a tragic, sad piece. Rolf Borzik wanted it like it was: with a feeling of wanting to live and to love. In January 1980 Rolf Borzik died after a long illness. He was 35 years old.

I knew at once that I mustn’t let myself be overcome by grief. This awareness gave me strength. It was also with Rolf in mind that I should continue working. I had the feeling that if I didn’t do anything then, I would never have done anything again. I knew that I could give my grief, my respect a form by doing a new piece.

The piece was called 1980. As always, we asked a lot of questions in the rehearsals – also questions going back into childhood. I had asked the set designer Peter Pabst, who had worked with many directors – both for theatre and film – to do this work with me. It was a great stroke of luck for me when he agreed to do the set for the piece 1980.

For more than 27 years now, Peter Pabst and I have been involved with great pleasure in the adventure of doing a piece that doesn’t exist yet. But that is not all. For me Peter Pabst is not only important as a set designer, but through his advice and actions, for us all and for the many concerns of the dance theatre, he has become indispensable. Many, many stages have come about.

For example:

- The curtain rises – a wall – the wall tumbles – a crash – dust; how do dancers react to this?

Or you come into the auditorium: meadow – smell of grass – mosquitoes; everything that happens is very quiet.

- Water: it reflects; it splashes; it makes noises. Clothes become wet and stick to the body.

- Or: Snow is falling – it might also be blossoms…

Each new piece is a new world.

He and my dancers have accompanied myself on such a long and difficult path and continue to go with me in great trust, for that I am very grateful. They are all pearls. Each in his own way, each in a different form. I love my dancers. They are beautiful. And I am trying to show how beautiful their insides are.

I love my dancers, each in another way. It is close to my heart that you can really get to know these people on stage. I find it beautiful, when at the end of a performance you feel a little bit closer to them, because they have showed something of themselves. That is something very real. When I am engaging somebody, surely I hope that I have found a good dancer, but besides that it is something unknown. There is only the feeling of something, which I madly want to know more about. I try to support each of them in finding out things for themselves. For a few, it goes very quickly; for others it takes years, until they suddenly flourish. For some, who have already danced for a long time, it is almost like a second spring, so that I am really amazed, what all appears. Instead of becoming less, it becomes more and more.

One of the most beautiful aspects of our work is that we have been able to work in such a variety of countries for so many years. The idea from the Teatro Argentina in Rome of working with us on a piece that was to come about through experiences gained in Rome was of decisive, I could even say fateful, significance for my development and way of working. Since then almost all of our pieces have come about from encounters with other cultures in co-productions. Be it Hong Kong, Brazil, Budapest, Palermo, Istanbul…and also your own wonderful country. Getting to know completely foreign customs, types of music, habits has led to things that are unknown to us, but which still belong to us, all being translated into dance. This getting to know the unknown, sharing it and experiencing it without fear started in Rome. It all began then with Viktor. Now the co-productions are simply part of the dance theatre. Our network is getting bigger and bigger.

I once purchased a buffalo’s rib-bone from Native Americans at a powwow in North America. This bone is inscribed with a large number of tiny symbols. I then found out that all the people who had acquired a part – just like I had – had written their address in a book. So this buffalo had spread everywhere. Together we all form a network in this way – like this buffalo that had spread throughout the whole world. And so everything that influences us in our co-productions and flows into the pieces also belongs to the dance theatre forever. We take it with us everywhere. It’s a little bit like marrying and then becoming related to one another.

As a company, too, we are very international. So many different personalities from such a variety of cultures…how we influence each other, inspire each other, and learn from one another. We don’t only travel – we ourselves are already a world of our own. And this world is constantly being enriched anew by encounters and new experiences.

In 1980 I met Ronald Kay, my partner, during a visit to Santiago de Chile. A poet and professor of aesthetics and literature at the Universidad de Chile. Since 1981, the year in which our son Rolf Salomon was born, we have been living together in Wuppertal. After having to experience how a person dies, I have now been allowed to experience how a person is born. And how one’s view of the world changes as a result. How a child experiences things. How free of prejudice it looks at everything. What natural trust is given to someone? In general to understand: a human being is born. Experiencing independently of this how and what is going on in your own body, how it is changing. Everything happens without me doing anything. And all of this then keeps flowing into my pieces and my work.

It is a special and beautiful coincidence that I have been living and working in Wuppertal for over thirty years. In a town that I have known since my childhood. I like being in this town, because it is an everyday town, not a Sunday town. Our rehearsal room is the ‘Lichtburg,’ a former cinema from the fifties. When I go into the ‘Lichtburg,’ past a bus stop, then I see almost daily many people who are very tired and sad. And these feelings too are captured in our pieces.

I once said, “I’m not interested in how people move but what moves them.” This sentence has been quoted many times – it is still true up to the present day.

For many years we have been invited to give guest performances all over the world. The journeys and invitations to foreign cultures have enriched us tremendously. Wonderful friendships have grown from many encounters. And so many experiences are unforgettable. Once we played The Window Washer in Istanbul. At one point in the piece, the dancers show photos from the past: pictures from childhood, of parents… They say, “That’s my mother,” or “That’s me when I was two years old.” Later they all show each other their private photos and go into the audience to show them to the public. Suddenly in this performance, the spectators took their own photos out as well – that was indescribable: how everybody was showing their photos with wonderful music playing in the background. Many people were crying.

Through these and many, many, experiences we have been richly blessed. And each time I try to give a little back through the pieces. But each time I have the feeling it is not enough. What can you give back? How can you give something back? Sometimes I have the feeling it is not possible at all. I sense so much and what I can give back is so very little…

And so my fears before each new premiere have remained to this day. How should it be different? There is no plan, no script, no music, and no set. But there is a date for the premiere and little time. Then I think: it is no pleasure to do a piece at all. I never want to do one again. Each time it is a torture. Why am I doing it? After so many years I still haven’t learnt. With every piece I have to start from the beginning again. That’s difficult. I always have the feeling that I never achieve what I want to achieve. But no sooner has a premiere passed that I am already making new plans. Where does this power come from? Yes, discipline is important. You simply have to keep working and suddenly something emerges – something very small. I don’t know where that will lead, but it is as if someone is switching on a light. You have renewed courage to keep on working and you are excited again. Or someone does something very beautiful. And that gives you the power to keep on working so hard – but with desire. It comes from inside.

I have travelled a long way. Together with my dancers, and with all the people I am working with. I have had so much luck in my life, above all through our journeys and friendships. This I wish for a lot of people: that they should get to know other cultures and ways of life. There would be much less fear of others, and one could see much clearer what joins us all. I think it is important to know the world one lives in.

The fantastic possibility we have on stage is that we might be able to do things that one is not allowed to do or cannot do in normal life. Sometimes, we can only clarify something by confronting ourselves, with what we don’t know. And sometimes the questions we have bring us back to experiences which are much older, which not only come from our culture and not only deal with the here and now. It is, as if a certain knowledge returns to us, which we indeed always had, but which is not conscious and present. It reminds us of something, which we all have in common. This gives us great strength.