Interview avec Elisabeth Clarke, 4.6.2023

Dans cette interview, Elisabeth Clarke décrit son parcours dans la danse, depuis son enfance à Philadelphie, en passant par ses expériences avec Maurice Béjart et son travail avec le célèbre compositeur Karlheinz Stockhausen. La première rencontre d'Elisabeth avec le travail de Pina Bausch a été transformative; elle a été profondément émue par les performances brutes, viscérales et chargées d'émotion. Ses souvenirs mettent en lumière la nature internationale et multiculturelle de la compagnie, et comment cette diversité a influencé leur travail, en particulier dans des pièces comme "Le Sacre du printemps", où son héritage africain a apporté une perspective unique sur les qualités rythmiques et physiques de la chorégraphie. Elle décrit son temps au Tanztheater Wuppertal comme une manière d'apprendre à voir la beauté et les luttes des gens ordinaires, et d'aborder le monde avec un "regard aimant".

| Interviewé/interviewée | Elisabeth Clarke |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Caméra | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20230604_83_0001

Table des matières

Ricardo Viviani:

What do you remember of this space? How different is it now? Do you remember the first time you set foot here?

Elisabeth Clarke:

I remember the first time I set foot in here. I was very shocked because it was so dark and so dim and so dingy. And I thought, how are we going to be able to create in this space when we can hardly see each other? And somehow we got used to it and it was wonderful to have a space that was almost as big as as the stage to create on. We got used to it and how it is now? It's like it's exactly the same as it was then. It's really it's exactly the same. It's like going back in time.

Ricardo Viviani:

So let's go back in time to your interest in dance. How'd you come to dance? In what kind of context was that?

Chapitre 1.1

PhiladelphiaElisabeth Clarke:

When I started to dance, I was in Philadelphia. Just a very lively little girl. And whenever I heard music, I would start to dance. My mother liked to listen to classical music. So I would jump around and spin and dance and knock things over. At some point she asked me: "Would you like to take dance lessons?" And I said, "Oh, yeah". Then I started to take children's dance lessons. It was very creative,I had a wonderful teacher. I think she was responsible for me continuing to dance because she worked a lot with imagination and using our senses, translating them into movement. This was when I was four or five years old. So that was kind of a paradise, and I continued. Later I started to take real ballet lessons. I'd like to tell you about that because as a little girl in Philadelphia, and especially a little black girl, ballet was so far away from the experience that we had. My mother looked for somebody teaching ballet, and she found an old Russian woman who was teaching ballet in a little studio up a flight of stairs.

Elisabeth Clarke:

And I remember going in there and, putting on my ballet clothes and standing at the barre. This woman was like no one I had ever seen or met before. I mean, she was someone totally new in my experience. An old Russian woman just was not part of my experience until then, so I was really fascinated and a little bit afraid. There we started doing real ballet lessons, she was very strict: there was a right and a wrong way. You did not speak and you didn't interrupt, and so on. I was really fascinated because that was something completely different from all the experiences I'd had until that. So when I went to ballet class, I was in an environment, and in a world that was mine. Unlike anything that I had at home or in my neighborhood. It was mine. It was my special thing. That's why I loved it so much. And I loved the fact that it was clear and strict. So I became really fascinated with ballet and I just just kept going. I just kept going with that. I remember always walking up these little stairs and entering the studio, and it was a different world, one that I preferred.

Ricardo Viviani:

Were there performance opportunities, would she do end of the year recitals?

Elisabeth Clarke:

No, she didn't. The teacher I had before, did end of the year recitals. But this woman, she did not do that.

Ricardo Viviani:

So, how did that progress? What did come after that

Chapitre 1.2

École du ballet de PennsylvanieElisabeth Clarke:

When I was about eight or nine years old, my mother took me to a performance of the Pennsylvania Ballet. It was the first ballet performance that I had seen and they were doing Carmina Burana. Carmina Burana is not music that would appeal to a young child, but I was fascinated. I was totally fascinated. I watched them do it and, I thought: that's it! That's what I'm going to do. That was my decision, I am going to do that. I'm going to be a dancer. Go on stage and do stuff like that. So, I enrolled in the School of the Pennsylvania Ballet. So things just went their way from there. I was awarded a scholarship from the Ford Foundation and I was able to attend as many ballet classes as I wanted. After that, I went to North Carolina, to the North Carolina School of the Arts when I was 13 and came back to Philadelphia. When I was 15 and went to New York to the School of American Ballet. And then at 17, I was finished with high school. That was the year that Maurice Béjart came to New York for his first tour in the United States. My mother told me that he was going to have an audition for his school. She said: "maybe you want to go to this audition, because they're doing acting and dance and so on."

Chapitre 1.3

Maurice BéjartElisabeth Clarke:

On the day of the audition, I was going to go to the to the movies with my friend Jodie, and I called her and she wasn't home. And I thought: "Oh, what am I going to do? Oh, yeah, there's that audition. Well, I guess I might as well go." So, I went. It was supposed to be in a studio, but there were far too many people, so they changed it to the theater where they were performing. So, all of these people got on the subway and went to Brooklyn. It was at the Brooklyn Academy and there were like 500 people at this audition. When I walked in, I thought: "okay, New York, 500 people, at least 300 people are much better dancers than I am, for sure. So actually, I have no chance." So I was really relaxed. It turned out that we first did a classical barre, and then we were supposed to do some contemporary, some modern dance.

Elisabeth Clarke:

The woman that came out to teach the modern part, was someone who had been at the school where I was when I was very little, so I knew what she was going to do. I knew the technique. It was it was Horton technique, and I knew what she was going to do. I went through that very easily, and then we came back and did some more classic, then some more modern. Hours and hours had passed. People from the company were sitting around watching this. Maurice Béjart said to us: "Now, I want each of you to do a one minute solo improvisation, to show us who you are." That was very difficult for a lot of the ballet people because they don't improvise, but I grew up going to this school where we did improvisation. So I thought: "Oh, I can do that!" So, yeah, I did it. Actually, I have no idea what I did; I know I did a lot of jumps and I used a lot of space. That's all I know. Afterwards, people were very impressed, and Mr. Béjart was also very impressed. So, I was accepted into the school of Mudra. Instead of going to university, I went to Mudra. That was the beginning of my being in Europe, with 17.

Ricardo Viviani:

I think this is the first time that somebody mentions the Mudra School. To put that in context, what was being done there? Maurice Béjart was a driving force as an innovator in ballet at that time.

Chapitre 1.4

École MudraElisabeth Clarke:

When Maurice Béjart was in New York, it was amazing. It was a controversy. There was controversy discussed in the newspapers. Is this ballet? Is this good? Can we accept it? Because, New York was used to the New York City Ballet and Mr. Balanchine. Then, came this person from Europe with such a wild, for New York taste, really wild way of choreography and dance. Giving men a position in the ballets that no one in New York was used to. For me as a 17 year old girl, seeing all of these incredibly beautiful, strong men dancing, I was fascinated, I was sold. The Mudra School was the same kind of thing. It was a wild idea, we had lessons in classical ballet and modern dance, singing, acting, yoga, flamenco and improvisation. It started mornings at 9:00 and we were usually there till about six in the evening: classes all day. It was tuition free because of some grants. One of our biggest supporters was the Gulbenkian Foundation. We got lots and lots of lessons. We could do experiments: we experimented with different ways of doing theater, using ballet and speaking while we were dancing, and so on. It was a place of extreme artistic freedom. There were people from everywhere: everywhere in Europe and the United States, from all different countries, lots of different languages. It was fantastic and it was such a privilege to go to that school.

Elisabeth Clarke:

So, people coming from Mudra were doing fantastic things. The first year of Mudra a company called Chandra was founded, which did not exist for very long, but they worked together, and then people started to peel off and do separate things. Maguy Marin formed her own company and became one of the premier choreographers in France. And Juliana Carneiro da Cunha went to the Théâtre du Soleil with Ariane Mnouchkine. There was Alain Louafi, who did a lot of things with the company, but also began to work with Karlheinz Stockhausen at the same time as I did. We worked together for Karlheinz Stockhausen. That was a really special. So, people from Mudra were doing groundbreaking work, wherever they went.

Chapitre 2.1

Karlheinz StockhausenRicardo Viviani:

Which year was that? And tell us about the next work that you did, was it with Karlheinz Stockhausen?

Elisabeth Clarke:

I entered Mudra in 1971. And it was a three year program, but in the third year, I injured my back really badly. So, I couldn't do classes and Mr. Béjart came to me and said: "What are you doing next month?" And I said: "Well, Maurice, I'm not really doing anything." And he said: "Could you go to Germany? Because Mr. Stockhausen has written a piece, and it's a piece with movement. He actually he wanted me to do it, but I can't. So, I asked him if I could send him a couple of my students." So he sent Alain Louafi and me. We went to Stockhausen's house, and met him. First of all, I have to say that Maurice Béjart was really my mentor and my Meister for all things connecting to a deep personal sense of self, and spirit, and art. Then I went to Mr. Stockhausen, who also had a way of connecting spirituality and art, but he was totally different from Maurice Béjart. I kept meeting people that were so unique, and Mr. Stockhausen was also quite unique. On the one hand, he was a composer with his mind in the spheres, and on the other hand, he was a very down to earth German guy. Sometimes it was a little bit confusing working with him. His thing was precision. So, this was in 1974, I came to Germany and started working with Stockhausen. From Maurice Béjart I learned to be open, completely open to all artistic ideas, and from Stockhausen, I learned that you need to be clear and precise about your expression of these ideas. So this was a further step in this university of artistic development.

Ricardo Viviani:

Here we are in 1974. How long did that work go on, and how did you get in contact with the work of Pina Bausch, and eventually come into the company?

Chapitre 2.2

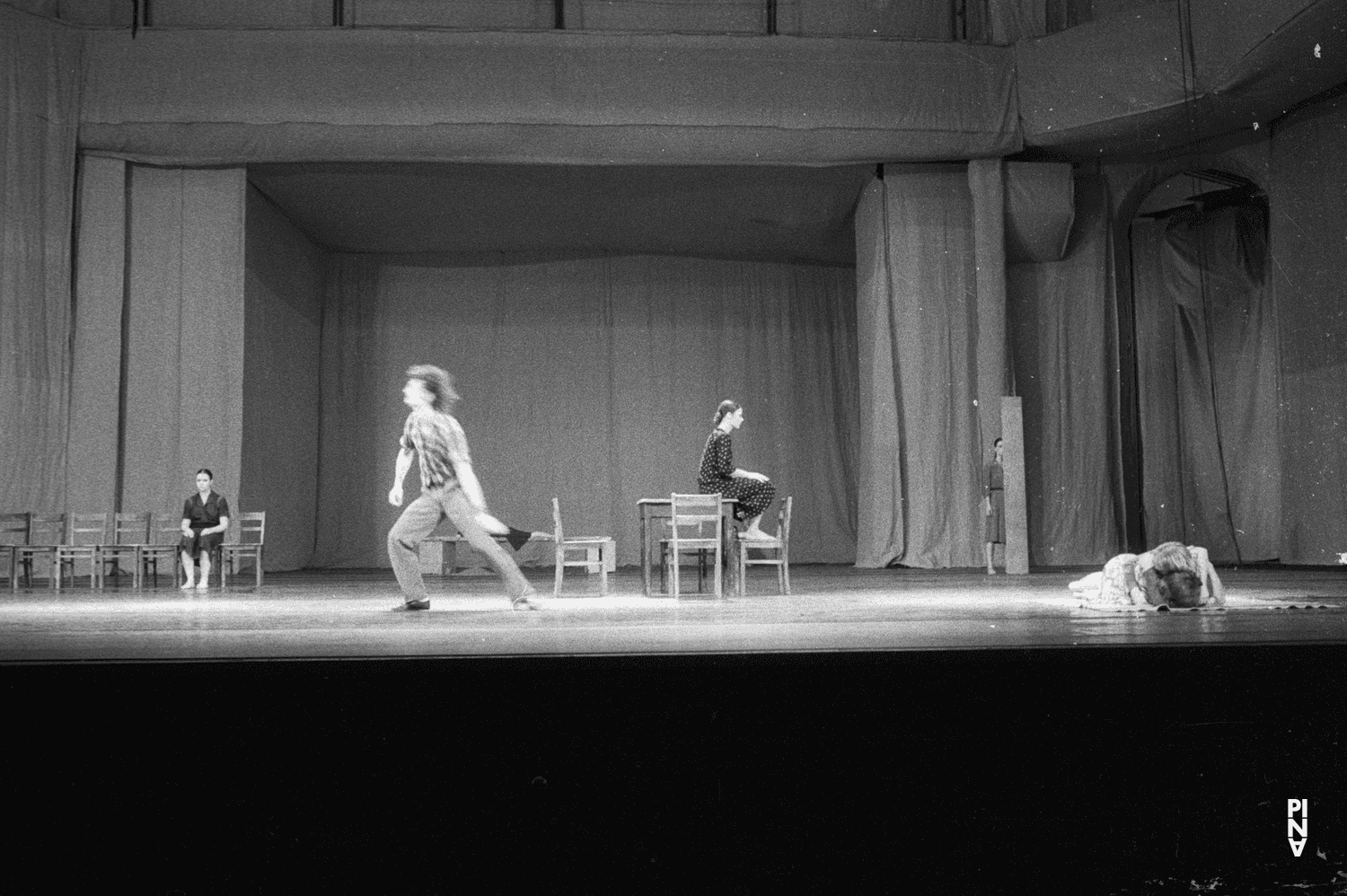

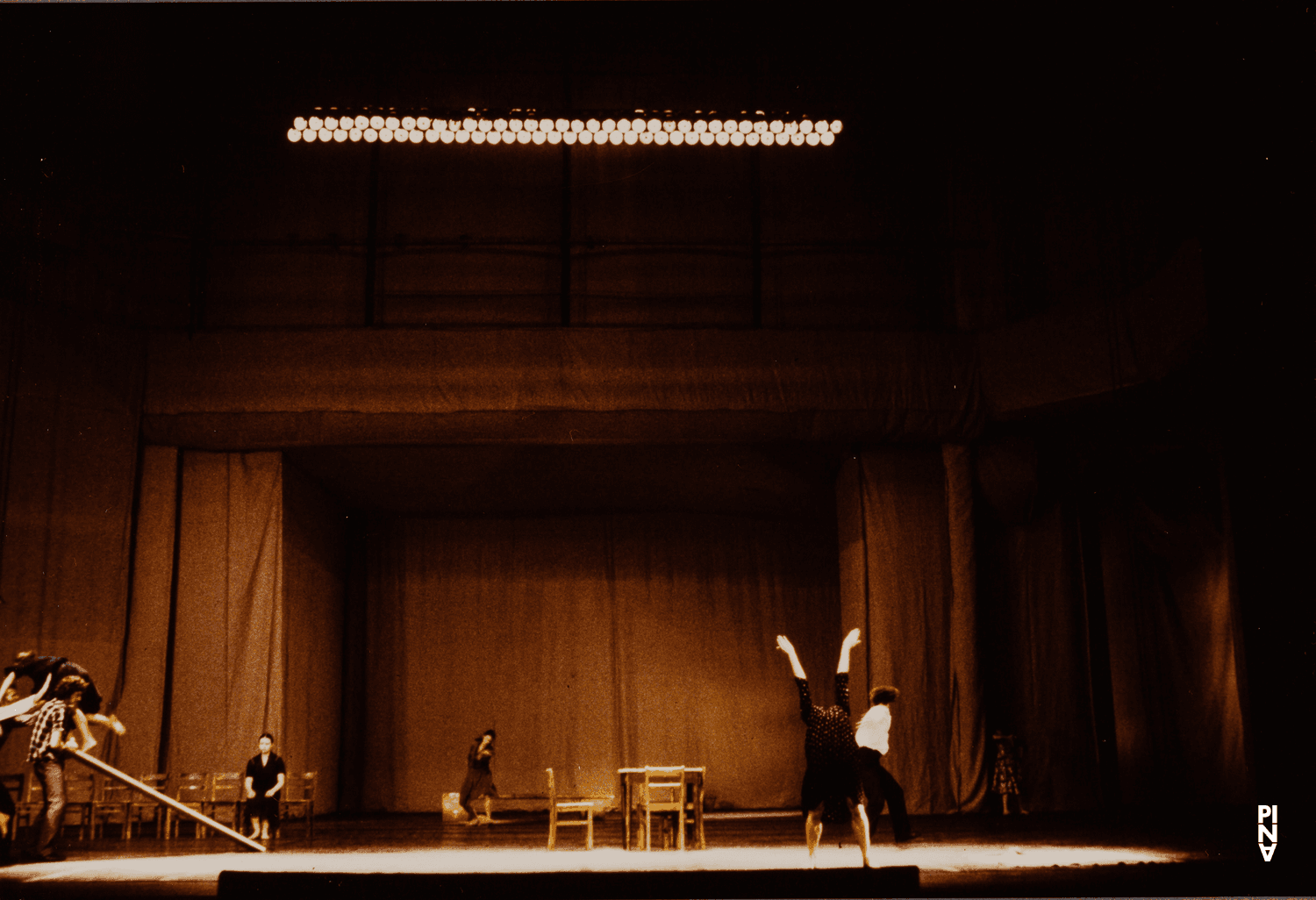

Pina BauschElisabeth Clarke:

We started in 1974 and I worked with Karlheinz Stockhausen for the next sixteen years, on and off. While I was there I met my, at that time, boyfriend. He lived in Cologne and he told me: "Around the corner from me and there's a pub, and the woman who runs it with her husband, she's a dancer, and maybe you would like to go to this pub and talk to them." When I went there, it was a dancer who had been at the Pennsylvania Ballet, and I knew from the time I was a child. We started talking and she said to me: "You know, there's this woman in Wuppertal. I think you should go there, because I think the two of you could maybe get along. So, I looked up when trains went from Cologne to Wuppertal. I just went. I mean, I didn't call, there was no audition, I just went and asked: "Can I train with the company today?" "Yes, you can." And Pina was not there in the morning, I took class and then people from the company started to talk to me, especially Vivienne Newport, Marlis Alt and Jo-Ann Endicott. Vivienne said: "Why don't you come to my house for lunch today." So, I went to her house for lunch. In the meantime, Jo-Ann had called Pina Bausch and said: "Look, there's this really interesting girl here. Maybe you should come over and see her." So, in the afternoon we went back to the theater. Pina sent everybody home and worked with me alone for 3 hours. That's how that happened.

Ricardo Viviani:

So, at that point, you haven't seen the work?

Elisabeth Clarke:

No, at that point, I hadn't seen the work. Afterwards, when she said she would be very interested in having me join the company, I went to a performance. I think it was the next night, and it was the Stravinsky Evening. When I saw "Sacre", I was sitting in the balcony in the front row, and if this piece have lasted 2 minutes more, I would have fallen off the balcony. I was so drawn to it and so moved by it. There was also the piece "Cantata" [Wind von West], and I thought that was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. I thought, if I could do that, then I will have done everything I need to do as a dancer, because there is nothing more beautiful than that. So I was really touched and moved by the work from the first time I saw it.

Ricardo Viviani:

Did Pina Bausch talk to you about after those 3 hours, inviting you back again? And how did that happen?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Oh, well, that was kind of funny. She invited me back the next day and watched class and said: "Come to lunch with me." So, we went to lunch together and we talked. We talked and we talked and we talked. It was very funny, there's one thing that I remember from this conversation. We talked about everything, but very often, I laugh. And Pina asked me: "Why do you laugh so much? I think maybe you don't understand life." And she said: "If you understood life better, you wouldn't laugh so much." I remember telling her: "Oh, I understand Pina. I just understand different things than you understand." When I look back on the work that we were doing at that time, it was a time of understanding that behind making things seem like they were okay, behind conventions, going very deeply, there were things that we didn't really want to talk about – not we, in the company but we, as a society did not really want to talk about.

Elisabeth Clarke:

The kind of cruelty that we inflicted upon ourselves and out of this frustration on one another. Pina was able to shine such a strong light on that just by looking at what people actually do. It was it was wonderful working with with these things. I can see now, what she meant by saying if you understood, you wouldn't laugh so much. I really can. I can see what she meant, especially when we were creating "Bluebeard" [ Bluebeard. While Listening to a Tape Recording of Béla Bartók's Opera "Duke Bluebeard's Castle"]. There's nothing funny about that "Bluebeard". I mean, everything that's in that piece is true. This is how we deal with each other, or how we dealt with each other, especially in relations, in close relationships, in couples relationships. Well, I definitely didn't understand that at the time.

Chapitre 2.3

Tanztheater WuppertalRicardo Viviani:

In the season of 1975/76, there were created the pieces The Seven Deadly Sins and "Songs" [Don't Be Afraid], which are basically two pieces that deal with abuse. In the following season we have "Blaubart", as you mentioned, and Come Dance With Me which has plenty of abuse in there, as well. But let's start with "Todsünden" [The Seven Deadly Sins]. You came in the company for that production. How was that process?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Well, it was interesting because we were working with people from outside the company as well. The process was, at that point still, I'd say a normal process. Pina Bausch would show us the movement. She would work as a choreographer and we learned the things and there was a bit more freedom in certain parts, but not so much in The Seven Deadly Sins. But in the other piece

Chapitre 2.4

Les Sept Péchés capitauxElisabeth Clarke:

Fürchtet Euch nicht [Don't Be Afraid] there was more room for individuality. Like, for example, the scene with with the dolls: she sat up and she explained: "You are going to be dolls and she is going to manipulate you." But we were given the freedom to how we would be these dolls, what kind of dolls we would be, and what the movements were. For other parts of them, she showed the movement and we learned the movement. And we had to sing, not so much, because there were other people that were brought in to sing these these Bertold Brecht and Kurt Weill songs. Still, we had to sing a little bit and I thought: "Well, cool. You know, dancers can open their mouth and make noises." Yeah, that process was still something that, as a dancer, you would recognize.

Ricardo Viviani:

As far as the the sets and the customers, there was some some peculiarities about the sets. Do you remember about that? Can you talk a little?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Yes the set was a street. What happened is that there was a street in Wuppertal, I don't know which street it was, and they took a mold of that street to make the set. So, the set of The Seven Deadly Sins was actually a Wuppertal street. The costumes were suits, very narrow, restricting, etc.. Wonderful is the fact that the costumes were telling the same story.

Chapitre 2.5

"Je n'ai jamais regardé en arrière !"Ricardo Viviani:

So, now you are in Wuppertal, living in Germany. You've been away from Philadelphia for five, six years by this time. Did homesickness play a role there?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Never. I never looked back. I was happy to be away from the United States. I was especially happy to be meeting these amazing artistic personalities. I mean, you have to imagine going from Maurice Béjart, to Karlheinz Stockhausen, to Pina Bausch. I felt this could never, never happen to me in the United States. So, I was never homesick.

Chapitre 3.1

Wind von WestRicardo Viviani:

So, the next season you probably had to learn the piece "Cantata" [Wind From West] and also "Sacre" [The Rite of Spring]. As we talked about your background in dance, how was learning those movements? Was there something that was challenging or it was just the work of a dancer? How was that experience for you?

Elisabeth Clarke:

"Cantata" was something that was sort of familiar for my body, but "Sacre" was not something that I'd done before. For learning "Sacre" I have the advantage of having this African heritage. So at least, the rhythmic parts of it were easy for me, but the movements were really, really difficult. The movements themselves were really difficult because I don't have such a supple body, and for this you really need to be quite supple. So what I did not have in flexibility, I guess, I had in strength and rhythmic understanding. But "Sacre" was really hard, I remember the first time we went on stage to do "Sacre", there were a couple of people in the company which was their first time too: Mari Di Lena, me, and a couple of others, and I was sure I was not going to survive it. I was sure I was going to leave my life there on that stage. When it was over and I was still alive, I was surprised. I was really surprised. What I love about "Sacre" is that it is exactly what you see. You see people getting exhausted. You see people falling down and getting dirty and so on. We did not have to produce anything. All you have to do is actually do that movement, the way it's choreographed, and all of those things happen naturally. I think that the first piece that I ever saw where it was like 1 to 1. There was nothing produced about it.

Chapitre 3.2

Le Sacre du printempsRicardo Viviani:

One interesting thing that you mentioned was having this African heritage and "Sacre". We have a company doing The Rite of Spring with artists from the African continent. Can you elaborate a little about this relationship between having an African heritage and "Sacre"? Maybe we might shed a light on our new production.

Chapitre 3.3

Patrimoine africainElisabeth Clarke:

Okay. I'm going to go out on a limb here. Whenever I have been on the African continent, I feel coming up through the ground, through my feet and through my body, I feel a different energy. It's immediate. It's coming from the center. I can't say emotional, but it's in contact with an energy, which has to do with with the ground, the earth, the air, the plants, even in the desert, in the silence, in the space. I felt that every time I've gone to Africa. "Sacre" [The Rite of Spring] also does that. It's absolutely not in the head. European dance was and is still very much in the head. It's like you have an idea, then you have to find a way to put this idea in a form. It's like what I was saying about Mr. Stockhausen. African dance does not come from an idea. It comes from an experience. You experience the world around you and the dance comes from that. Now, I did not grow up in Africa. However, there are certain things that are passed on within the black community.

Elisabeth Clarke:

Through the time of being transported away from your home, and the suffering that was there. There was also always this unspoken and non theoretical way of passing things on. Being in contact, and I say really strongly, being in contact with the Earth is something that was always passed on, or the way you move: like this kind of movement (shows), this is passed on. So yes, there's something about a heritage and about an approach to artistic things that is African, and now it's diaspora. Because there's been so much communication, and there's been so much procreation between peoples, that this thing is now diasporan. And it's specific, when I am in Africa and I'm dancing with people from that continent, there are certain things that we have in common. But, because I also have a dance tradition which is European, there are certain elements, that I have mashed there are not elements of African dance. So, we sort of give and take, and this give and take comes to a diasporan expression of movement. So, that was my advantage. You know, the the strong rhythm and the earth and literally the earth is something that an European child will not necessarily experience.

Elisabeth Clarke:

There's one thing that's very special about The Rite of Spring, because of what I was speaking about – African Heritage, is how did Pina Bausch come to this? I found this really interesting, because her way of moving was really like the movement coming out of the African continent. I was fascinated because, in a certain way, she shouldn't have been able to do that, but she was. Which meant for me that she was in contact with something universal, and she allowed herself to do it. I saw some some videos of the company coming from École des Sables and to me it looked like: "Well, that's what The Rite of Spring should have been like the whole time." It's so close to a physical tradition for them. Yes, certain things are different. The way Stravinsky wrote it and the way that piece was done, it looked like – when I saw those those videos I thought – that's what it should have been from the beginning. Actually, it doesn't matter. If you can find this contact to the universal experience of the world through the earth, and through the sky, and through the sound of waves, and get away from the intellect – which happens when you dance it – it doesn't matter who does it, and that's beautiful.

Ricardo Viviani:

I would like to stress one thing within the Stravinsky program to segue into another issue. The Stravinsky evening is composed of three pieces with very different character each. I'd like to segue that into how the company was composed at that time as a multi-ethnic company. Do you remember your colleagues and how all of that would influence the work? Pieces like "Cantata" [Wind From West], a theatrical scene as in The Second Spring, such varied pieces composing this evening. In that light, would you have some thoughts on that?

Chapitre 3.4

Elizabeth de HongrieElisabeth Clarke:

We were dancers working with Pina Bausch. Pina is very German, so some of the influences are going to be very, very German. [Wind From West] / "Cantata" The story of Elizabeth from Hungary giving bread to the poor, which was not allowed, so she had her basket hidden under her dress. When she was asked, what are you carrying, she said, I'm carrying roses, and so they lifted the cover and the bread had turned to roses. This is the story of Saint Elizabeth. This kind of historical religious story was informing "Cantata". It's a legend. In the the beginning of the piece, the way that the hands move is like what you see in medieval paintings this kind of movement or position of hands (shows). So, a lot of it was like paintings from the Middle Ages. It was also something that was very legato and really flowing the whole time. It also left a small taste of melancholy. Still very beautiful piece. I'm really glad I got to do that.

Chapitre 3.5

Der zweite FrühlingElisabeth Clarke:

Then, for The Second Spring actually you had to be German from a certain time, and from a certain class to really understand The Second Spring. This thing with the the pillow (shows), a chop so that the pillow does that, Pina explained to us. She said this is the way people did that in their living rooms, if you had a proper way of living, your pillow always had that crease in the middle. So, we were multiethnic, but we were all living in Germany, in Wuppertal. Wuppertal at that time was real a kleinbürgerlich / petit bourgeois place. A lot of the population was very old, very narrow minded with a very narrow horizon. That's also where she came from, she distanced herself from that, but that's where she came from. So this crazy, multiethnic, multinational group of people was trying to sort of fit in to Wuppertal. There was no way we were going to fit in. If you wanted to get an apartment, you had to talk to these people, so there was kind of a tension there. I already explained what the soul of "Sacre" [The Rite of Spring] was. So, it had to do with Pina's experience, but it also had to do with our experience. That's why The Second Spring is so amusing: it's because this petit bourgeois was trying to make the world predictable, and by making the world predictable, you have to make it small. And we all had, in some way or another, experienced that feeling, but certain specific things were specifically German.

Ricardo Viviani:

So, as a performer, was there a challenging shifting of gears, to go from Wind From West, to The Second Spring and to The Rite of Spring?

Elisabeth Clarke:

No, because they were so different, that you just entered into a different universe for each of them. If they'd been a little bit more similar, it would have been a problem shifting gears, but that was like speaking French or English or German.

Chapitre 4.1

Un monde différentRicardo Viviani:

So the company, by now, in the late seventies started to become an international company: with the Festival in Nancy, having tours sponsored by the Goethe Institute. One that's special was the Asian Tour. Do you have recollections of that?

Elisabeth Clarke:

I have such recollections of that. I mean, I never thought I was going to be able to go to these countries. It was amazing for me, for all of us. We started off in... did we start off in New Delhi? Yes, I think so. Even on the bus, between the airport and the hotel, it was like we're not in another country or on another continent, we are in a different world. We're really in a different world. I remember this being the first experience for a lot of people, not all, but for a lot of people in the company, the first time they experienced seeing extreme poverty. That shook all of us, even those of us who'd had something like that before, but never to that extent. So, this is what we started this tour with. We started the tour with the shock of being in a completely different environment, and that was only the first day, and we were there for six weeks. I have pictures in my mind. I remember we were in Sri Lanka, and we are on a bus going, from the airport or something, and I remember seeing someone where I thought: that is the most perfect picture of a human that I've ever seen. It was someone who was just standing in a yard and had a big vessel and poured water over his head. Just this position (shows), I didn't even see this guy's face. I thought: "This is perfect, this is what humans are." That's one recollection.

Chapitre 4.2

Choc culturelElisabeth Clarke:

Or I remember being in Hong Kong, walking down the street with Arthur Rosenfeld, and he said to me: "you know, here it's sort of like New York, except everybody's Chinese." I remember going to a snake farm and seeing a snake shed its skin for the first time, someone explained to us what it meant when a snake sheds its skin. I remember being on a stage in Bangkok, which was a stage used for traditional Thai dance, and this stage had two levels, and we had to be really careful, because suddenly in the middle of the stage you would have a step down. I remember so many things about this tour, and how close it made us all. The last or the next to last performance was in Calcutta, and it was "Sacre" [The Rite of Spring]. As we were doing "Sacre", the audience started to get really excited, very agitated, they started to leave their seats. People were leaving their seats and coming down to the front of the stage, shouting, it felt very threatening. There were people at the front of the stage shouting, and you thought they were going to climb up onto the stage and stop us from torturing this young girl. So what happened is, at some point they just cut the lights, which was maybe not the smartest thing to do, but we ran to the back of the stage. They took us away, some people had to have tranquilizers because they were just so upset. This performance was, as I said, 1 to 1. I only ever experience that in this company, working with Pina: there was no barrier between art and life.

Elisabeth Clarke:

That tour was with the Stravinsky evening and the Brecht/Weill evening [The Seven Deadly Sins], and we stopped doing the Brecht/Weill evening. Then we only did the Stravinsky evening, because the reactions were too negative. Also the Goethe Institute said: no, we don't think you should do this. Yes, cultural differences again. So then, we just only did Stravinsky evening after that, and the actors and singers just came along for the ride. They were there, they did the whole tour, but the didn't have ever to perform it anymore. I think they did one performance and then no more.

Chapitre 4.3

Mis en placeRicardo Viviani:

One more technical question about that tour: was it for Pina, or for the company challenging setting up for different stages?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Totally. It was a total challenge setting up different stages because the stages were so different when we were in the Philippines. We had a stage that was enormous. It was huge. The tarp for "Sacre" just looked like a small rug on it because the stage was so huge. We had, as I said, this stage in Bangkok with the two levels. Then we were somewhere where there was no technique, they improvised putting up some lights, they really improvised. I remember we were told, don't tell anyone what we did here, because it was absolutely not safe. Then we had a stage that was so small. I think that was that same stage and was so small that we had to do "Sacre" in shifts. So, part of the company would do one part and they would then leave the stage and the others would come on, and do another part because we couldn't be on stage at the same time. It was so tiny.

Chapitre 5.1

KontakthofRicardo Viviani:

So after the season of 1977/78 a new piece was was created called Kontakthof. Do you remember that process? Was it different from before and how was it different?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Yes, it was very, very different from before. There were moments where there was choreography. There were movements which we had to do, but the process of Kontakthof was one where we began working through tasks: Pina Bausch would ask a question and then we would sort of improvise scenically the answers – sometimes with speech, sometimes without. They were little short things, and Marion Cito was sitting there, writing down all of the questions and all of the scenes. Nothing was connected to anything else, and we didn't really know what we were doing. Which was cool because we focused simply on the question and finding an answer. That was also a process where it became clear, that what Pina wanted was our subjective truth. She didn't want an idea of something, she wanted the thing itself. For example she asked: "If you were in a cafe and you wanted to get attention, what would you do?" She wanted real stuff, what would you do? So, somebody dropped their bag and everything spilled out, or someone had an attack of sneezes. So these are the kinds of things that she would have Marion write them all down. Then at a certain point, she started putting things together.

Elisabeth Clarke:

I mean, this process had already begun with Bluebeard, but it became actually THE process when we were doing Kontakthof. She would say: "Um, let's see the Café. Only the girls do it, and the men just sort of stand around." And we would do that, then she'd say: "Okay, let's see the same thing, the Café, and only the men do it, and the girls are all in a corner with each other." We would do that, and we would do lots of different variations of things that we had done before, which sometimes we didn't remember, but it was really great because Marion had her notes. And we would do all of these variations of things, and repeat them over and over until Pina Bausch saw what she wanted. She didn't know what it was that she wanted, but when she saw it, she said: "Yes, that's it. We will do that way." So, we had to remember what we did. I remember I had some notes somewhere in my closets at home. I have some notebooks with my notes from this piece, and it's like as if I didn't know what I was writing, there is no way I can make sense of this. That was the process, and we had a lot of freedom, but when it was decided, it became precise. Now, that was kind of fun, and at the end, we still didn't really know what we were doing, because there was no story. We started at A and proceed and get to Z, but each of us sort of made a story for ourselves to be able to get through.

Ricardo Viviani:

Interesting, I like to hang on that point. To get through that evening, you had a path for yourself, a story. What was yours? Or maybe it's not so concrete that you can say, but how did you deal with it?

Elisabeth Clarke:

I remember dealing with it by remembering some of my experiences in romantic relationships that were not working. For example, wanting to be seen. Going through this, wanting to be seen, and sometimes thinking that I'm seen, and then realizing that I'm not. That was my story, but it came from my experience.

Ricardo Viviani:

And this ballroom environment, where people come to meet, did that resonate in any way, like a prom or anything like that?

Elisabeth Clarke:

This room? There was, at the time, here in Wuppertal a Puff [a brothel], and it was called the Kontakthof. I remember my colleague, John Giffin saying: "Let's go there and see what it's like." So we went. We went in, and it looked pretty much like what the set was. We were only there for a few minutes, because they came and told us that I could not be there. We explained to them we wanted just to see what it was, because we were working on a piece. We didn't say more than that, but they still told us to go. It was like long enough to see and to feel this atmosphere. Awful place, it felt like a parking garage with bad neon lights, and I thought: "Wow. That's pretty strange." What I thought of was a lonely hearts club, all of those people that were there were all very lonely.

Ricardo Viviani:

We talked about Kontakthof in the sense of a Lonely Hearts Club or failed love, if we put it in contrast with how we talked about The Rite Of Spring, how much the structure of the piece carries, and how much that relies on the performance, from the dancer with personal memories?

Elisabeth Clarke:

The pieces of this time with Pina Bausch relied very much on each of us being engaged with who we are on stage. We were not playing characters, there were no characters. It was all: what you see is what it is. We were all there with our own experiences and personalities. This is what made the pieces what they were. It was like the company was that's what the pieces were. The vision was Pina's vision. But the material was who we were.

Ricardo Viviani:

As a performer there's also a learning curve. How to learn to be yourself on stage. How was that brought about? How was this process of learning what truthfulness of being yourself is?

Elisabeth Clarke:

It was an organic process getting there, because when I came, there was a choreographer showing us the movement. Then, when we started having a bit more freedom and being asked these questions – it didn't all happen at once – we moved in that direction. The other thing was that when Pina Bausch had the feeling that somebody was not being honest, she didn't put that in the piece. When we were gathering material and she had the feeling that it is not true, she would not put that in the piece. So, through processes like that we learned to just answer the question. People think that it takes a lot of courage to show yourself like that on stage, but actually, for me anyway, it didn't take courage, it just was okay. That's what we're doing now, and it seemed to be a very natural thing to do.

Chapitre 5.2

ArienRicardo Viviani:

After after Kontakthof comes another piece called Arien. Your recollections about that one piece?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Arien. I don't think I have ever done anything that has been as intensely personal as Arien. It was an intense time for us, a very intense time for us. The story is one of our colleagues became very ill. He thought at first: "Well, I've got the flu and I'm going to stay at home." But he just didn't get better and didn't get better, and he went into the hospital. All this time we were doing rehearsals and finding material. We had one day here in this room that we just went crazy. The question was: "You're at a party and then you find out all the doors are locked. What do you do?" And she let this go on for almost an hour, it only stopped when one of the dancers took a roll of toilet paper and was wrapping people up, then took a match and was going to light the toilet paper, then it stopped. But that was just one rehearsal, we had lots of rehearsals. The thing was, during this time our colleague was just not getting well and we were all really involved, making calls to the Institute for Tropical Medicine, driving his family back and forth.

Elisabeth Clarke:

We couldn't reach him. He was going farther and farther and farther away from us. He was in fever. He was in delirium. They packed him in ice to bring the fever down, but nothing could bring this fever down. The despair that we felt was in the piece. It was there. There's a scene in Arien where it's raining, and the stage is covered in water. Someone runs onto the stage and begins to dance furiously, really dance and the waters are splashing all around. Someone else runs out onto the stage and calls their name, frantically trying to get them to stop, and they won't stop and they run away. And then comes the next couple and the next couple and so on. Yeah. It was so intense. Each time I did that scene – I don't know what the others were thinking, but I can imagine that it was like that – it was like our sick colleague was moving and dancing, and someone else was calling frantically, trying to get him to come back. That all was in Arien. Oh, yeah, very intense. Also at that time, after Luis P. Layag passed, Rolf Borzik was also very sick. He got better, then he got sick again. And he got better and then he got sick again. We had this specter of death in there, and the helplessness that you feel. Parts of Arien were very light, but when it was not light, it was so intense. I remember, several times really weeping on stage while I was dancing. Yeah. That was Arien.

Ricardo Viviani:

We talked about the sets in The Seven Deadly Sins and in Arien there are sets, props and costumes as well. Everything is very unusual, do you have recollections of that?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Yeah, I do. One of the things was that for each performance of Arien I have a cheese sandwich and a chocolate pudding from the prop department. They have to make this or buy this every time because I had a scene where I was eating chocolate pudding. That was fun. The other thing was this hippopotamus in Arien. They made a sort of latex cast of a hippopotamus, and they had two people who were getting into this hippopotamus, and they really couldn't see anything. So, they had a walkie talkie, and Hans Pop was standing at the side of the stage with a walkie talkie and telling them: "Okay. Straight ahead. Stop. Okay. Turn to your right. Go. Stop." He was directing the hippopotamus. The problem was that the latex fumes made them feel very dizzy. There was a time where the hippopotamus would go off to the side, and they could take a little breath. But actually, it was kind of an awful job to do, because you were in this latex thing, it was really hot and so on. But they did it. From the outside, of course, you couldn't see any of that. At the premiere of the hippopotamus was not finished, it still had to dry. So we had Hans Dieter Knebel from the theater in Bochum come and play the hippopotamus. It was wonderful, it was really wonderful. He didn't say anything, he just walked around. Sometimes he would sit down, stand up and walk around, and look a bit sad the whole time. It was it was fantastic, and I'm not sure which version I prefer.

Chapitre 6.1

Rolf BorzikRicardo Viviani:

In Arien all the sets and costumes were created by one person: Rolf Borzik. Do you remember, or have recollections of working with him? How was the relationship in the work? How things were created? In this room, how things would appear and disappear?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Rolf Borzik was brilliant, just brilliant. He understood Pina Bausch and I mean, he understood what she needed. If she had an idea, she would talk to Rolf about it, he would then come up with an idea and talk to her. I mean, like this one picture in Bluebeard where the women are on the wall. This was just an image that Pina had, and he made it possible to do it, he figured out how to do that. Or the costumes: he would not go to the costume department and look through old stuff, these things were designed and made for us. My costume for Arien, this beautiful silk gown, was made for me, and I wept when we had to get it wet in the water. Rolf Borzik took each of us, individually very seriously, and said: "Oh, for you, I can do this, and for you I can do this." Rolf was so amazing, just really amazing. He knew what was needed, and knew how to produce that. Say, for example, the idea that we're going to have the stage covered in water, to figure out how to do that. Or how do you make a hippopotamus? To figure these things out and never to say no. He never said no. He always found a way to do stuff.

Chapitre 6.2

ExpériencesRicardo Viviani:

So in 1980, in the summer of 1980, there was another extensive tour, sponsored by the Goethe Institute, of South America. There were two programs: for the first time since 1978, Café Müller was played again, some of the Stravinsky pieces and Kontakthof. Do you have recollections of places, and things that were special about this tour that you could tell us?

Elisabeth Clarke:

I remember having a really good time with this tour. Okay. I will tell you first, the most special thing that happened on that tour. We went to Santiago de Chile. A lot of us did not want to go to Santiago de Chile, because we did not want to perform for the ruling elites, Pinochet and his friends. And we had a real discussion about it, a real discussion about it. Pina Bausch said: "You have to go, and you have to do this performance." It was the only time I ever heard her say something categorically: you don't get to have an opinion about this. I never heard that. That was the only time I ever heard that. So we felt that, somehow, we had to show that we're not okay with this, I mean, there has to be something. So, we decided that we didn't want to take a bow, but we had to do that too.

Elisabeth Clarke:

The next day we had a workshop, because on these tours, we always had workshops. We were thinking what to do, and the decision was made to do the entire performance again, not on stage, but in the room where they set this workshop. There was no cost of admission. So, all of these students and young people, who couldn't afford a ticket, they all came. They were all sitting and standing on the perimeter around the walls, and we did the entire performance again. When we did The Rite of Spring the distance between the dancer and the first person who was looking was like that (shows), maybe. They were really close and this room had some windows, but the windows were high, like a gym. We did The Rite of Spring not in costume, we were in training clothes, these people got covered in our sweat, they could hardly breathe, and we could hardly breathe, but we were so together. At the end, we all fell into each other's arms, hugging, covered in sweat and tears. It was like a gift, it was so special. That was the most extraordinary thing that happened on this tour. To be able to give that made more sense than protesting and not going on stage. It made so much more sense. I think we dance better that day.

Elisabeth Clarke:

Other things on the tour. I really got to be a tourist as well. We saw a lot of touristy things. I also explained to Pina that everyone in Brazil can do that (shows) and make noise, everybody. We were having dinner in a restaurant, and she said: "Well, I don't believe that everybody can do." And I said: "Yeah, everybody can." So I just got up and walked to a table and I said: "Excuse me, can you do that?" And they said, sure, and then I walked to another table and they did it, so I said yes, I guess everybody can. Just a small thing that happened. Then, being in Rio de Janeiro and just thinking: "Wow. Where is this place?" I mean, to see this bay, Rio just looked amazing. I remember in Mexico City, they had oxygen tanks behind the stage, in case somebody needed oxygen. We had that in Mexico City and we had it in ... Bogotá, I think. I don't remember if it was in Lima or Bogotá, but I don't think anybody needed it. Which is actually surprising, but we were just so involved in what we were doing.

Ricardo Viviani:

Did you experience the Buenos Aires tango culture with the company?

Elisabeth Clarke:

Yes, we did. Someone from the Goethe Institute took us to a tango place, but not a tourist tango place, one that you only know if you live there. And yes, we experienced this really pure tango culture. The place was really dark. It was really interesting to see the sensuality of the tango, and it being just that what it was, not necessarily having any other consequence. It was just when you danced, when people were dancing, they were in an extremely intense and sensual connection. And when the dance was over, they would sit down and that was that. That was really fascinating. There was a guy playing bandoneon: a very short, small man, and when he played, he would get really red in the face, where you thought he was going to explode. Then, when he stopped, it was like, now I can breathe again. Then, he would play again, and it was this again.

Chapitre 6.3

IntensitéElisabeth Clarke:

I've spoken a lot about intensity. There seems to be what happens when you're around Pina Bausch. You get to have intense experiences, usually without words. That's the thing about having chosen that particular form of art, which goes through movement, and which goes through body and gives an intensity that you can't have in a discussion. The intensity of experiencing someone else, without it being sexual, without it being romantic. It's just being close to someone, to enter into their world and into their personality, and to leave it at that, to let that be enough. This is the essence of the experiences that I kept having in the time where I was working with Pina Bausch.

Ricardo Viviani:

We just talked about how all the experiences were so intense and we talked a bit about how in Arien, it was such an intense moment, an emotional moment for you and your colleagues. Was there a trigger for the time for you to move on, or how was that for you?

Elisabeth Clarke:

I can't say that it was a trigger because I did not feel triggered. Especially after the experiences of Arien, I felt like I've reached a point where I'm full, and this experience is complete. I remember Pina Bausch asked me: "Why do you want to go?" And I said: "Yeah. I have enough now." But not in the sense of "I have ENOUGH". I said: "You know, something can be good, and then there's a point where you have enough. It's like eating ice cream. Ice cream is wonderful. But there is a point where you have enough." And this is how I felt. I felt like there was something that was complete. It was round, it was complete, I have learned so much. I have been given so much and I gave so much and it was complete and so I could move to the next thing.

Chapitre 6.4

Qu’est-ce que le Tanztheater ?Ricardo Viviani:

I'd like to wrap it up. The experiences that you told us, and talked about, all of these people from Philadelphia to Maurice Béjart to Karlheinz Stockhausen and to Pina Bausch, linking from one into the other, getting this experience in 1980, about 40 years ago, I like to, maybe summarize these experiences into the one question:

What is Tanztheater?

Elisabeth Clarke:

What is Tanztheater? I don't know what it is, I do know what it was for me. For me, it was learning to look upon simple, ordinary people and have my heart moved. To pity for their struggles and admiration, that they keep going in spite of their struggles. Learning to see that and learning to reproduce that for these people on stage. That's what Tanztheater that was for me. Also to notice that I am exactly like they are. And so, to learn to move through the world with a loving eye, and to put this loving eye onto what I'm doing now was what it was for me.

Voir aussi

Mentions légales

Tous les contenus de ce site web sont protégés par des droits d'auteur. Toute utilisation sans accord écrit préalable du détenteur des droits d'auteur n'est pas autorisée et peut faire l'objet de poursuites judiciaires. Veuillez utiliser notre formulaire de contact pour toute demande d'utilisation.

Si, malgré des recherches approfondies, le détenteur des droits d'auteur du matériel source utilisé ici n'a pas été identifié et que l'autorisation de publication n'a pas été demandée, veuillez nous en informer par écrit.