Consoling Carnations – Peter Pabst in a conversation with Wim Wenders

Peter Pabst published the book Peter for Pina in 2010. In addition to many photos of his set designs, it includes a conversation with director and photographer Wim Wenders.

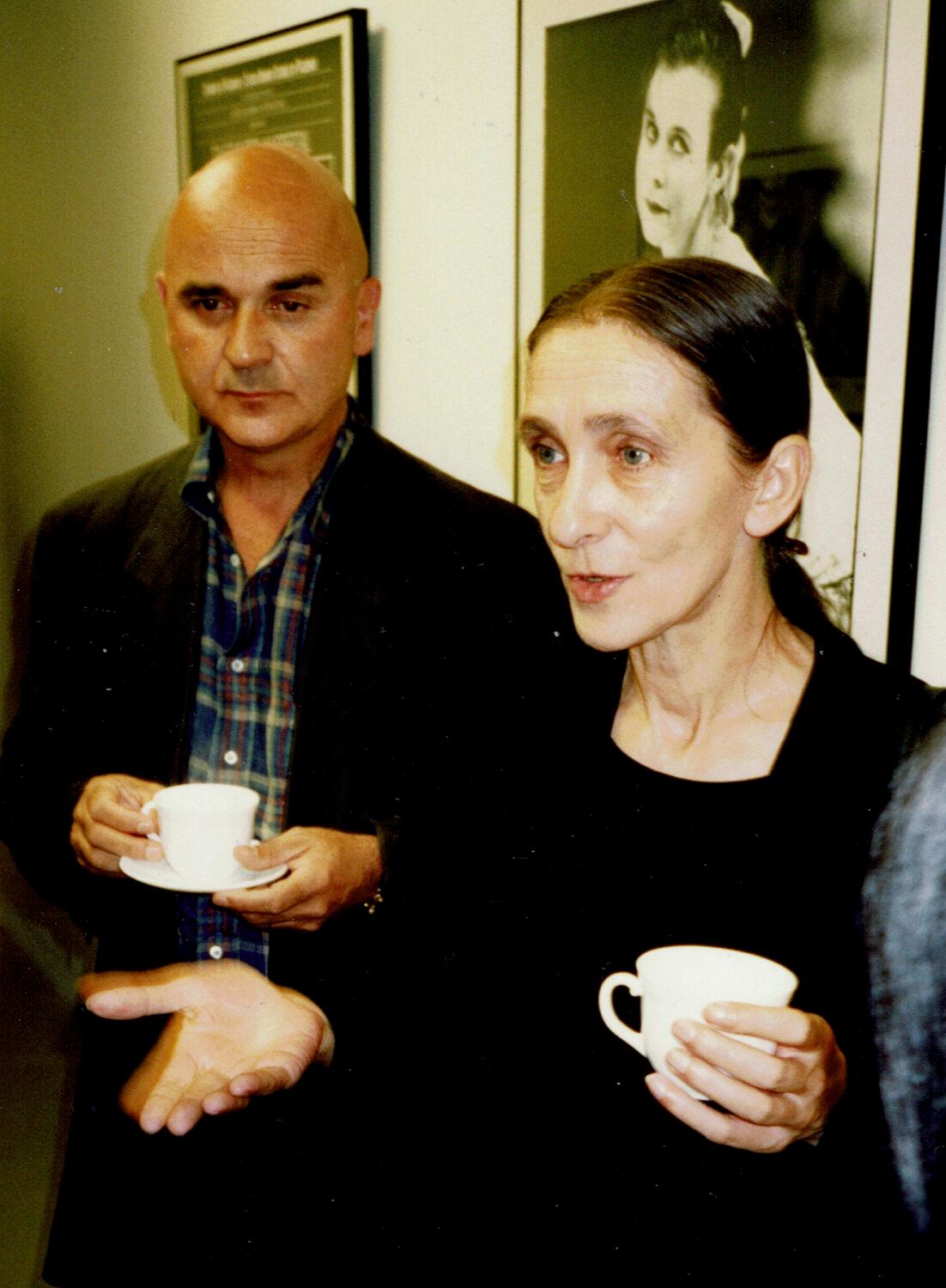

Wim Wenders and Peter Pabst in discussion

Wim Wenders: The Schwebebahn (suspended monorail) just outside your window! That would take some getting used to for me.

Peter Pabst: That’s actually why I’m here. There’s a story behind this room. I was always at the Tanztheater on a freelance basis, so I never had a set place to work. And then, at some point, I was granted asylum on this floor and took over two rooms. It’s just around the corner from the Lichtburg where Pina rehearsed. Eventually, I realized that Pina enjoyed coming here. Pina was always a bit hard to get a hold of, even when it came to looking at my models. I even started to record the models on video and then I would bring the tapes along to the rehearsal just so Pina could at least see them. But here, she always came here! That was nice. And later, when it became clear that we had to settle someplace else with the company, I said, “Why don’t we go where I’m already at?” And then we moved here and…

Wim Wenders: ...and then you immediately went for the best view...

Peter Pabst: we immediately took over the Schwebebahn (suspended monorail) side of the building, right away and it’s something that I’m happy about, still, to this day. From here you can see the Schwebebahn go by and below, in the Wupper, there’s an egret who is always perched on the same stone there. That was our bird; we loved him.

Wim Wenders: Well, that’s a very important thing, finding the right space, that is. Actually, that ties in nicely with what I wanted to talk about. Dancers need space to dance. They need room to move about; maybe you could even call it a “playing field” of sorts. How does the stage designer contribute to this space? Would you consider yourself a landscape architect in some ways?

Peter Pabst: (laughs)

Wim Wenders: (laughs) See, I did my homework.

Peter Pabst: (laughs) I was curious to see what you’d come up with.

Wim Wenders: Well, we have to start somewhere… So even if it just provokes further discussion: landscape architect, what do you say to that?

Peter Pabst: I’m not intentionally acting as such, but in a certain sense, of course there is some similarity between a landscape architect and myself. If I try and think back on my overall process, all of my thoughts begin with the floor, I think.

Wim Wenders: You must know an awful lot about floors, right? How many types of dance floors are you familiar with? What all do you know about them?

Peter Pabst: By now, yes, I know quite a few things about dance floors. About their appearance, their flexibility, how soft they are or the kind of resistance they offer, the sounds they make or their muteness. I’m constantly creating new surfaces to be used as dance floors. But one of the first things I always think about - and this was especially important for the piece that you just filmed, Vollmond (Full Moon) - is that it’s hell for dancers if the dance carpet gets wet. They fall on their backsides almost immediately.

Wim Wenders: But this isn’t the first time that water was used in one of Pina’s pieces, right?

Peter Pabst: …yes, that’s true, but it’s never been used on the dance carpet! These mats never served as dance floors before. If there was water, there was always something under it. With Arien (Arias), for example, where Pina had water fill the stage for the first time - I was completely jealous, I would have loved for that to have been my stage design - there was an old sisal carpet underneath. That was also a phase during which not much dancing took place.

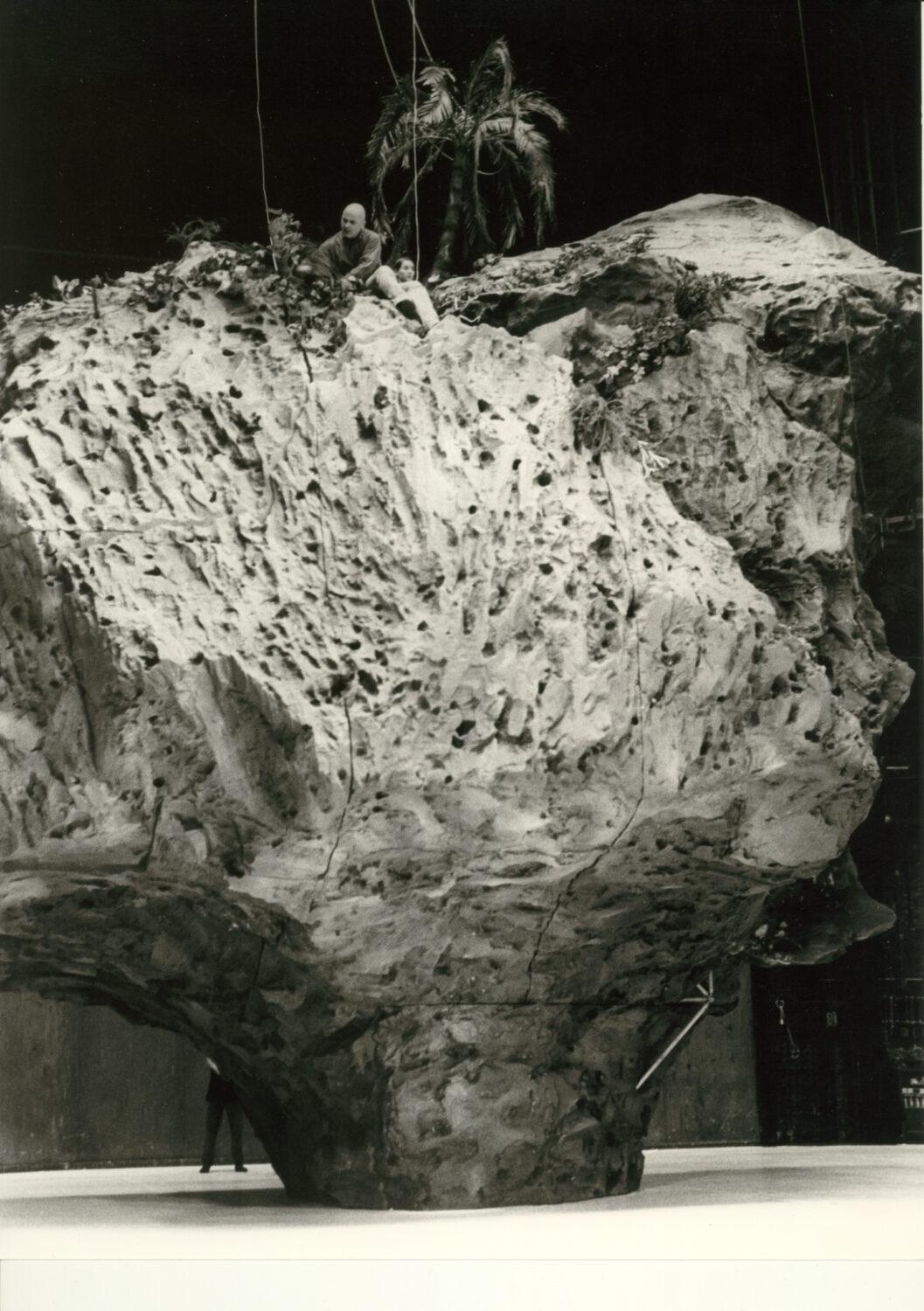

I also built her an island once, which moved, because I thought that a moving floor could actually be quite nice for dancers to work with. So I made a large island, at least 100 square meters in size, that was floating in water and that moved, or more precisely, that was moved by the dancers’ movements.

Wim Wenders: Which piece was that?

Peter Pabst: It was called Trauerspiel.

Wim Wenders: Yes, of course.

Peter Pabst: So they danced on an island that was floating in water. The island was covered with blast furnace slag - granulated blast furnace slag - and that kind of material is a real nuisance for dancers to work with.

Wim Wenders: That is one of my first questions actually, what was all over the floor in there?

Peter Pabst: Ah, yes, just awful…

Wim Wenders: ...was it blast furnace slag?

Peter Pabst: ...you know, it was so nice because it sparkled and because it was black. But it was like ground glass. I wanted to have a black floor. Everything was supposed to be black: black water and a black floor, and I tried and eventually I came with the idea of…what is the name of that small island near Tenerife…?

Wim Wenders: …Lanzarote...

Peter Pabst: ...I thought of Lanzarote with its black lava sand, but for some reason or another I just couldn’t get a hold of any. And then I found out that they ground blast furnace slag - a byproduct of steel manufacturing - around here. The granulate they make is used to sandblast large steel structures like bridges, for instance. That’s what its intended use is anyway.

Wim Wenders: A local material then, for the Ruhr anyway.

Peter Pabst: Exactly, and I prefer that. I don’t like to look through catalogs in search of theater materials. I like looking around here to find local products.

Wim Wenders: What did you use to ensure that the floor in Vollmond was nonslip?

Peter Pabst: That, well, that was the most difficult task because Pina said to me, “The dancers have been playing around with water a lot.” Those are often the first indications - if I haven’t been at rehearsals - and then she tells me something like that, then I know, well, it would probably be a good thing if the set design allowed for the usage of water. (laughs)

I really wanted to create a river. A dark, silent, calm stream… But I also knew that the dancers were going to be dancing a lot and using the entire stage to do so. Pina also said to me that things would become quite wild and reckless toward the end of the piece. If there was a lot of water on the stage, then the whole thing was going to get very wet once this happened. So I knew that I had to find a dance carpet that would allow the dancers to dance without inhibition or limitation whether the floor was wet or whether it was dry. As the stage designer, the last thing I ever want to be is a hindrance to the performers. And that became one of the most complicated…

Wim Wenders: Did a material exist?

Peter Pabst: No. At the beginning at least there was no material that I knew of, so I asked myself what sort of public places have to address similar problems. There were, I figured, almost undoubtedly strict regulations with regard to safety in such instances, and they must have found a way to solve such a problem. Public swimming pools for example, I thought, are just such a place.

At this time, the Olympic Winter Games were taking place in Turin. An Italian friend had designed a place for the Games that was used in the evenings to host presentation ceremonies. We had spoken earlier about his design for this place. So, I called up this friend and I asked, “What did you use for the floor?” I figured it was similar to what I was looking for in that there were many spectators who walked around on it even though it was wet and often subject to snow.

Anyway, I was always just poking around in these practical corners. That’s how I found a man in Hamburg who works with surfaces that are covered with water; more specifically, he designs surfaces so that they can be walked upon when wet—perfect for my river.

I also found a company that produces nonslip synthetic floors. They were, however, not perfect for the theater…they were very expensive, very heavy, and very rough—but it was something. Only then, unfortunately, it turned out that when the dance floor was dry that it was too nonslip. It was hurting the dancers’ feet.

So I experimented over and over again with the dancers rehearsing on small pieces of test material. But all of those materials were never really all that good and they needed to be very good. The end of the story then sounds almost like a joke: I took the flooring that was not slippery enough and sprayed it with a somewhat “less efficient” nonslip paint and that seemed to do the trick.

Wim Wenders: Apart from that, have you always limited yourself to black and/or white floors? What other type of dance floors have you designed?

Peter Pabst: I have never used colored dance floors while here in Wuppertal. I’ve used dance carpets in other colors elsewhere in the theater, but never for dance purposes.

Wim Wenders: So, with Pina, only black-and-white?

Peter Pabst: Here it’s black-and-white and nothing else.

Wim Wenders: It does seem as if it’s the best option if one hopes to emphasize the dancers.

Peter Pabst: Yes, and while I was here I was never all that interested in colored floors. There are a number of different materials to work with; I even toyed around with a transparent dance floor once. That one went up in France at some point.

Wim Wenders: What was beneath it then?

Peter Pabst: I played around with the model nonstop, using light and colors and then I laid photographs underneath of it. It was crazy.

Wim Wenders: I did something similar in my office once.

Peter Pabst: Oh?

Wim Wenders: I had a large office space, something like 80 square meters and I laid out an aerial photograph of Venice. It was a beautiful shot of Venice, you could see every canal and every house. We fused it together with some plexi-glass, laid it down, and you could walk over Venice. It was beautiful.

Peter Pabst: It’s beautiful because it’s crazy.

I remember that being a really joyful time for me; I actually amused myself quite a bit. The dance carpet that I found was actually similar to milk glass. You couldn’t actually see through it at all—something that we could have used when filming the door in Café Müller now that I think about—but when you laid it down and put something beneath it, you could see it as if you were looking through clear glass except, of course, the clear glass was a dance floor.

Wim Wenders: But that floor was never danced on?

Peter Pabst: No, we ended up not using that one because I came up with a different design. It was going to be for Nefés originally, but we ended up using it later in Água…there’s a short, comical scene where two dancers creep around beneath it. It looked as if they were just immersed in cloudy water.

Wim Wenders: Tell me about how you came to work with Pina? You did your first piece with her in 1980, so did you begin your longstanding partnership then?

Peter Pabst: Not right then, but soon thereafter, yes.

Wim Wenders: It must have been difficult to take over stage design in Wuppertal following Rolf’s death.

Peter Pabst: Yes, it was difficult for a number of reasons.

Wim Wenders: Talk to me about your piece 1980. In it, there is a deer standing in a meadow.

Peter Pabst: Well, before the deer could stand in the meadow, there had to first be a meadow…

Wim Wenders: …talk about a “playing field”…

Peter Pabst: In the most literal sense…and, once again, we begin with the floor.

The first thing that comes to mind when I think about working on 1980 is a groping sort of sensation, which was born out of my own shyness and cautiousness. That was really difficult. I knew of the sorrow and the loss. I knew of the close relationship that Pina and Rolf shared and the meaning Rolf Borzik held for Pina. And it was difficult at first to make a decision and say: “Okay, I’m doing this.” “I’ll give it a try.”

You can’t say, “I’ll do that,” you have to say, “I’ll try that.”

Wim Wenders: That shyness then was brought to life in the deer?

Peter Pabst: Probably. (laughs) That’s why in the many years since, the shy deer has been plucked clean. (laughs) Whatever the reason, he has managed to stick around and, in the meantime, has become one of the oldest members of our company.

Yes, it went something like this… Naturally, you are under enormous pressure and you think to yourself, I have to create something wonderful. I just have to. And I tried and tried, created every possible stage design and every imaginable model I could think of. And we kept trying - I think you could say it like that - we tried to converse, to talk to one another, something that one, surprisingly enough, always has to learn and relearn so that you can speak with each other. And then, possibly, at some point you no longer have to speak.

Wim Wenders: Pina wasn’t the most talkative person either.

Peter Pabst: No, not at all really, but that wasn’t much of a problem for us actually.

Not terribly long ago we had our first guest performance in China, in Peking, and the Director of the Chinese National Ballet, Zhao Ruhend, asked that Pina and I arrive two or three days early in order to attend a press conference and meet the people there. She also wanted to organize a meeting for us with some local Chinese artists. In this meeting, someone asked, “How do you two work together? How do you debate? How do you talk to each other?” And I said, “Well, by now, we’ve been working together for such a long time” - because it had been some 25 years by then - “After 25 years, we don’t have to talk that much.” Our minds played host to so many of the same images, more than we ever actually realized, we thought thousands of thoughts and had thousands of visions, which we never even realized.

Anyway, Pina interrupted me then and said, “My dear, we’ve never had to talk to each other all that much.” And I thought that was just wonderful because that’s probably one of the secrets as to why we were able to work with each other for so long, so fruitfully, and with such joy.

Wim Wenders: And the two of you did that for the very first time with the making of 1980… the meadow… how did all of that come about? The deer and the spotlight and the first stage design that you created with Pina?

Peter Pabst: It’s actually quite silly how it all happened because of the never-ending, roundabout process with which it began. Because we were running short on time, we discussed using a previous design. I even thought of planting a vegetable garden in the room used in Kontakthof. (laughs) As I said, this was the phase when there was not an excessive amount of dancing happening. But then, I remember, I had - in another context - leafed through a beautiful book about Fellini that Peter Zadek had just given to me as a gift - and in there, there was a photograph from the filming of La Dolce Vita, I think…a picture from a night shoot. And there was a field with all of the technical equipment from the film strewn about on it. The scene was immersed in such an unreal light, which is normal when one tries to light the nighttime as if it were daytime. I thought, “Wow, that’s beautiful!” If I just completely cleared the stage except for the walls and then covered it in real grass, then the theater is in a meadow…it would smell like grass and insects would move about freely in the light from the spotlights. I showed Pina the picture then and she was all for the idea, so I began. And that’s how it all came about.

Wim Wenders: So, grass that can be rolled out in strips?

Peter Pabst: Yes, the kind you can buy.

Wim Wenders: Do you have to water it?

Peter Pabst: Yes, you have to water it…and give it light, aerate it, sometimes even mow it. And at the beginning you have to clean it. That’s one of my favorite memories. Back in 1980, sod was still pulled directly from the ground. A special husking machine was used to skim about 5-6 cm below the surface of the field. There were three layers: the blades of grass, the roots, and the dirt. The pieces were then rolled in individual widths and delivered to the theater. Well, when we rolled out the first shipment on the stage it was obviously very dirty because the dirt from the underside was stuck to the blades of grass on the topside of the strip. In a normal garden, the rain takes cares of washing this away, but we weren’t expecting rain on the stage anytime soon. So, I went to the facilities manager here and asked him if he could send two cleaning ladies down to the stage with vacuum cleaners to vacuum the fresh grass. And he did. Well, I sat in the auditorium, not making a sound and watching these two women in their blue work uniforms. They were the very first “visitors” to this meadow that I had created and I heard what they had to say about what must have seemed like nothing more than a joke that some utterly absurd person had come up with. That’s just a memory now though because it’s been a long time since sod was taken directly from the ground like that, now it is grown using nylon nets and its free of dirt and germs.

Wim Wenders: Were the dancers able to move about properly on such a surface? Was that the first time that most of them had performed on such a surface?

Peter Pabst: No, the meadow was quite a new idea, but they had already gained some experience with similarly challenging surfaces…

Das Frühlingsopfer (The Rite of Spring), for example, had already been there, with peat moss. Then there was Arien, which featured water. Both of these remained quite unruly surfaces that were difficult to work with. I think the leaves that were used in Blaubart … (Bluebeard …) weren’t that influential, by which I mean that their effect on the elongation of the body and on the dancers’ movements was minimal. So the experience was not entirely new, only the grass and the technique used on it were new.

Wim Wenders: You made visible that which, thus far, had remained invisible…

Peter Pabst: …we took those things that one normally hides - the lighting techniques, the cameras, the monitors - and we simply put them on display in the field. And that’s something that I really like to do. I am a slovenly kind of man, not much of an aesthete, but rather someone who prefers things to be a bit sloppy. Anyway, this field was always more and more cramped. And then, at some point, I dragged a deer onstage. And that - getting that deer on that stage - that was far from easy.

Wim Wenders: Where did you find it?

Peter Pabst: Well, I called around a bit to a few natural history museums and to some taxidermists just to see what people had available.

Wim Wenders: It looks like Bambi…

Peter Pabst: I remember that both Pina and I briefly entertained the idea of calling the piece Bambi. (laughs)

Anyway, I just called around asking if anyone had a deer until I found one. I only discovered later that in many countries it can be quite difficult to travel with a stuffed deer.

There was also a sprinkler on the field. These things, these banalities, they suddenly worked, things that you otherwise could never design or do - in the meadow, they work.

Wim Wenders: I bet that interests you, piques your interest, when something doesn’t work or when someone says, “Impossible.” You’re the one always ready to give it a try, right?

Peter Pabst: Yes.

Wim Wenders: Then you want to be the one to do it…

Peter Pabst: Well, otherwise I think to myself, maybe I’m actually just kind of lame. But, if something doesn’t work, I just can’t have that…I’m not good at losing…I have to admit that. (laughs) I just don’t like it.

Wim Wenders: But when exactly are certain things introduced? I don’t fully understand that side of things yet. On the one hand you have Pina’s scenic ideas, her ideas with regard to dancing, but then there is this huge puzzle, if you can call it that, related to this topic, if you can even call it a “topic” per say… Where do the visual ideas come into play? At which point do you include yourself, or, do you just kind of slide in somewhere along the line? How did you productively interact with each other? I’d like to know more about that. When do ideas come to you from out of the rehearsal phase and you’re able to say, “Now I can get started.”

Peter Pabst: One always thinks that there must be some kind of point of departure, a concrete starting point. This, “Now we’re starting, now I’m ready to go!” that you mentioned, in my experience such a moment does exist when you’re working on a film or an opera, and even most times when you’re working in the theater, but that was never the case with Pina. Yes, with Pina there really wasn’t any assumption that there was a single point of departure: a single text, a singular idea about the piece, about the music, anything like that. Actually, it always became clear to me after the fact that I had actually already begun.

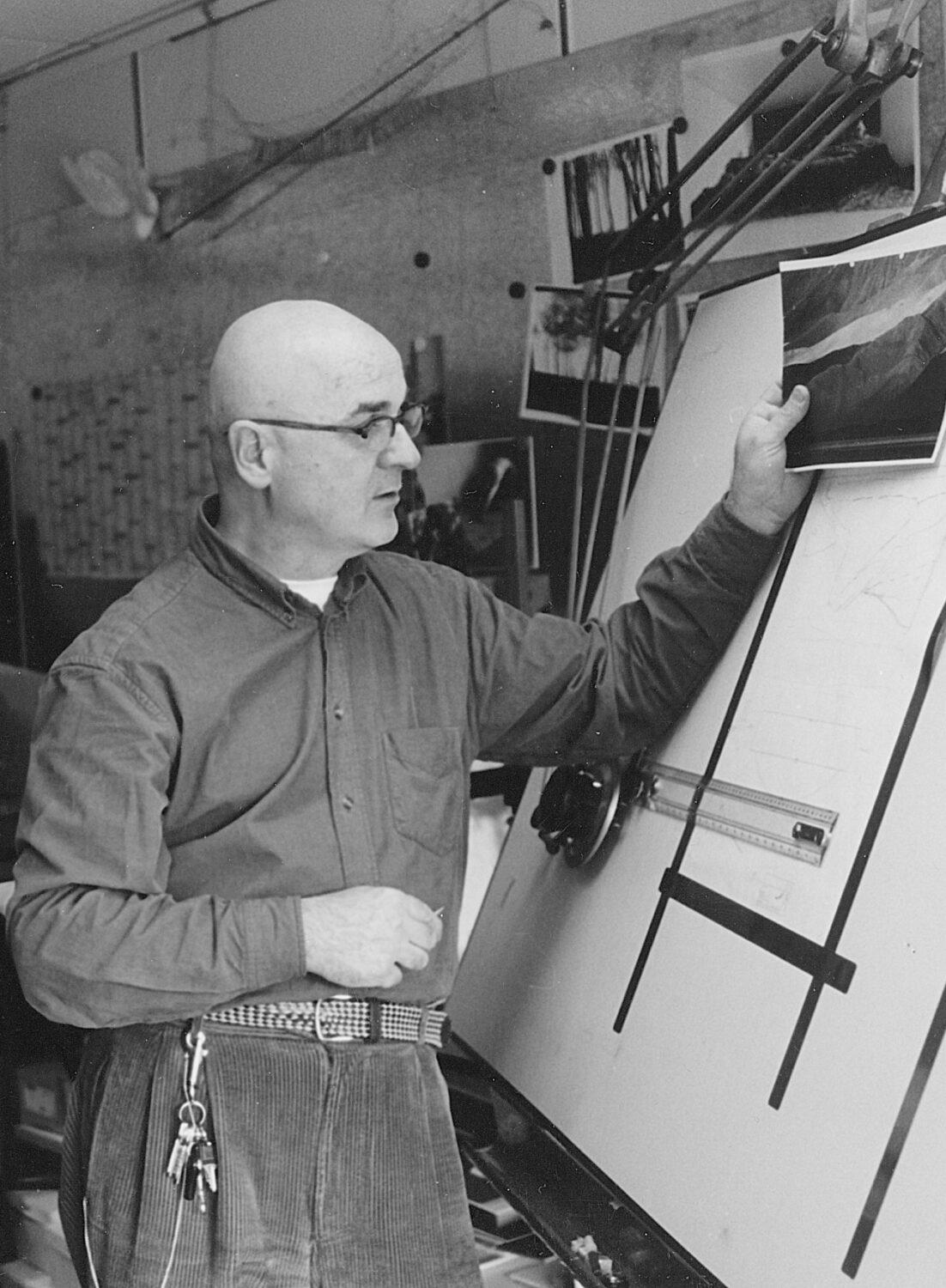

At the beginning I had this problem when designing my model boxes, they always seemed like these gaping black holes. And this wasn’t a problem that Pina could really help me with either; she didn’t have much of anything yet either. So I just began to play around so that there was at least something filling the emptiness that plagued my model boxes. Sometimes I put something in that I had already had.

We never talked about it beforehand, how something could come to be, probably because doing so early on would have limited Pina’s work. There should be, must be an entire adventure, a journey of discovery that takes place.

Wim Wenders: Nevertheless, it interests me, the way in which you both pushed each other along.

Peter Pabst: It sounds like a contradiction, I know. On the one hand, the process of approaching a new piece never really changed in the nearly thirty years that Pina and I worked together. On the other hand, we never really developed a strict recipe by which we worked that would allow me to clearly answer your question. We both began independent of one another. And in that stage I am certain that Pina had more concrete thoughts than I did. She just never talked about them, most likely because she couldn’t yet formulate them or didn’t yet want to. She was extremely cautious with her words.

Wim Wenders: Then it’s probably better if, rather than talking about things in a general sense, we take each piece individually and consider how things moved back and forth between you both within the context of each of them.

Peter Pabst: I know that I snuck up on many of the things I attempted rather unexpectedly, sometimes using pictures, sometimes using things that were already in model form. Mine was a search for small worlds that could play host to the world of one of Pina’s future pieces and the world of her dancers. At the beginning though this search was always somewhat aimless, diffuse, a game played amidst the fog if you will.

Wim Wenders: But at some point you must have known what could reasonably be put into one of your boxes and that, whatever that was, it had work with Pina’s ideas as well.

Peter Pabst: Yes, of course. It would have been idiotic to push for a set design that was absent of Pina or that went against her. But the beginning stages were never heavily formulated for us, everything was much more playful than that, much more tentative. And at first, Pina didn’t usually have very concrete ideas either. In our first five years working together, I was constantly asking her if she had any idea as to where something was going or where it could possibly go. And for five years I got the same answer, “You know, I am always trying to listen to what’s inside of me, but there is something covering it up, it’s not yet coming to the surface.” And after five years, I stopped asking.

Wim Wenders: Then it’s probably the case that she was actually quite happy when you came up with something concrete because it gave her something she could take hold of.

Peter Pabst: Yes, but not at first. In the beginning, Pina didn’t want anything. I think she wanted nothing more than to not be disturbed. Now that we’re discussing it, I think she wanted to see what she was discovering with the dancers at the beginning of a production, or what she was trying to discover with them, in a pure manner, unbiased by a geography or an atmosphere that I had created. She was simply looking without distraction and checking to see if what she found was any good. On a neutral surface - black dance carpets. And I didn’t push back against that. Maybe once or twice I mentioned an idea or laid a picture on the table, a sketch. But if Pina did not immediately react, I packed it away by the end of the rehearsal. I thought to myself, the suggestion is either not good enough or she doesn’t want to see anything right now. I never tried to push anything through. My philosophy was that an idea must already be so good in its first moments that it just radiates…

Wim Wenders: Then countless ideas must have fallen by the wayside.

Peter Pabst: Many, an unbelievable number actually. It was similar to a lavishly filmed movie, a shooting ratio of at least 1 to 10 or something like that.

Wim Wenders: Then let’s go through everything starting from the beginning. We’ve already talked about 1980, what were things like with Nelken (Carnations)?

Peter Pabst: With Nelken…

Wim Wenders: ...a classic!

Peter Pabst: At some point, Pina and I talked about flowers, about Holland. In spring they play host to these countless fields of flowers.

Wim Wenders: But those are tulips!

Peter Pabst: Yes, you’re right, they’re fields of tulips. And they are breathtaking, it’s like something out of a fairy tale and when you see them...

Wim Wenders: A huge colored surface…

Peter Pabst: ...it’s just incredible! The way that it was sowed with this intensity and in which the color combinations were disseminated…it was as if the farmers were all painters. You think to yourself, I must be crazy, this frenzy of color. Pina had also talked about fields blossoming with carnations. She had seen them in Chile. And I found carnations fascinating because in the sixties they maintained a rather formal disposition; they conformed to a middle-class sensibility. For whatever reason, one always brought carnations along when visiting someone…normally, small bouquets of five or seven flowers. And later on, for this reason, carnations were seen as quite bourgeois despite the fact that they’re actually lovely flowers.

At the time, we hadn’t yet settled on this as our stage design, but it was at least a possibility that was out there. And then I took the idea and tinkered around with it until I came up with some crafty, off-the-wall piece of work, that much I know.

Wim Wenders: Using plastic flowers or what?

Peter Pabst: No, this was a model. It’s impossible to draw a field of carnations.

Wim Wenders: How did you do it then?

Peter Pabst: I tore sponges into the smallest bits possible, stuck each piece on a pin, and then dipped each pin into some pink paint. Then I just stuck them wherever I could to allow them to dry. I did that until I had about (laughs) 3000 of them. It was a really contemplative process; I didn’t see or speak to another person for an entire week. Me! But when I was done, I had created a field of pink carnations in my model box. But then I thought, that’s probably a bit too saccharin. Just around that time I made a film with Tankred Dorst. We filmed it on the border with the former East Germany. And there was always this border fence, staggered across the varying levels of the area, and between those areas—chained to running wires—ran these half-starving German shepherds who tried to catch anyone who dared to jump the border. Horrible!

So this crossed my mind and I thought, maybe I should have the field of carnations being patrolled by German shepherds, combat against that sugary sensation. Pina liked the idea of dogs barking…

Wim Wenders: Sure…

Peter Pabst: I wanted to stretch running wires to the right and left of the stage and thought, I’ll call the police and they’ll give me two German shepherds. They just have such beautiful, well-trained and behaved German shepherds. Unfortunately, an official with the Wuppertal Police Department explained to me that there was no way I would get the dogs from them. Why not? “Because when a riot breaks out, our dogs are trained to run in amongst it all. And if they were to be put on a stage with loud music and dancers moving all over the place, then for them it might as well be a riot and no one will be able to hold them back anymore.” He gave me some good advice though: I would be better off looking for privately owned dogs, preferably from families with children.

Wim Wenders: …and where they make a lot of music.

Peter Pabst: And where they make a lot of music! And where they have become accustomed to everything and (laughs) are ready for just about anything. So I found two German shepherds who met all of these requirements, but they didn’t work out that well either. The one discovered the chairs on the side of the stage that was being used for Nelken. It was soft and upholstered with velvet and he laid down on that chair—obviously the most comfortable he had yet to encounter in his entire dog life thus far—and absolutely refused to come down off of his seat…and he proved successful in his refusal.

Wim Wenders: He was the wrong dog for the job.

Peter Pabst: He was the wrong dog for the job and the second one wasn’t much better. He actually had a nervous breakdown the first time that the music was turned up. He planted himself and didn’t stop peeing after that. (laughs) Anyway, it didn’t really come together. They did whatever they wanted to do and were constantly barking, the thing that Pina was really looking forward to pairing with the pink carnations, at least in theory. But after a while, as background noise goes, it became very stressful and we both thought that there must also be moments in the piece during which no dogs were barking. And so, what we ended up with in the end was four dogs that were controlled by their owners the whole time.

Wim Wenders: That’s wonderful…how an idea like that develops over time.

Peter Pabst: Yes, it has a life of its own. That’s why it’s so difficult to answer the question: how does something originate, or how does something begin?

Wim Wenders: And then the dancers had to learn how to move amidst all of the carnations?

Peter Pabst: Then they had to learn how to dance in the carnations. Yet another thing that was far from easy! And again, first, the carnations had to be there.

I had a very small budget for the piece. You could buy plastic flowers in Germany, but they were only available at a high price. And no one had carnations. As I said before, they were seen as being bourgeois and no one wanted to buy carnations anymore, let alone plastic ones…so no one was manufacturing them anymore.

I calculated that for the Wuppertal Stage I would need about 8000 flowers. They didn’t have that many flowers at the market, I couldn’t afford to pay for that many flowers, and we were about four weeks away from the premiere. Now, there’s a reason or two to lose some sleep at night.

But, I woke up around five one morning; I was drenched in sweat and in a real panic about the whole situation, wondering where else in the world people make plastic flowers. And then - it just came to me - I saw hardworking yellow hands before me…making flowers. Of course, I thought, Asia! I was in a frenzy, found the number, waited until nine, and then called the business sections of every Asian embassy in Bonn. “Are plastic flowers made in your country?”

I got lucky with the Thai Embassy. They gave me the name of a contact in Hamburg and put me in touch with a manufacturer in Bangkok. Mr. Rumpf, the importer in Hamburg, called me back after a few hours and made an offer, 8000 carnations in three different colors to be delivered via airfreight to the Wuppertal Opera House within twenty days.

Out of that, a friendship was formed, because he has handled all of our flower needs for a long time now. He had an older Chinese man working in manufacturing - he made, I assume, jeans and t-shirts - who had manufactured plastic flowers at one point in time. And whenever I came to them with an order, then this man would switch jobs and take to producing pink carnations for us, and - later on - other types of flowers as well.

Wim Wenders: Always 8000 of them right off the bat?

Peter Pabst: No, it worked just as well with two thousand of them. In any case, I received the flowers and did so with enough time to spare, and I’d even managed to get them for a price I could afford. It was a small miracle.

But, the first time they were planted, now that was really miraculous…this glowing field of pink carnations on the stage of the Wuppertal Opera House… it wasn’t saccharin at all, it was like something from a dream.

And, of course, then came a very rude awakening: they break when the dancers dance in them!

Wim Wenders: Yeah...

Peter Pabst: …I never forgot that. I really loved Pina and one reason was that in this particular situation she showed how easy she made it for someone think and act in an entirely crazy manner, even when it comes to stage design.

What she said to me was, “We could create a scene where all of the carnations are consoled.” She referred to this as “consoling carnations” and what she meant was that the bent flowers would be straightened once again. (laughs) And I never forgot that gesture from her…Pina wanted to console my carnations. We didn’t end up doing that though because it turned out that their deterioration was equally beautiful. There was an unbelievable aesthetic effect created by the field of carnations…the way in which it glowed with warmth at the start of the piece. Then later on there is this moment when, in a deaf and dumb language, Lutz Förster tells, or dances The Man I Love and suddenly the lights come up…the entire stage just shone in this blazing shade of pink. So we realized at some point that it was actually very beautiful that the flowers would break throughout, beautiful that they were in some way ruined. Excuse me; I’m probably talking too much…

Wim Wenders: ...no, this is wonderful; I always wanted to know these things.

Peter Pabst: Let me say one more thing about the whole “consoling carnations” situation. That’s a small example of the free, complicated, and yet breezy fantasy that Pina displayed in her work. It was unique. And that’s how she handled difficulties: not burdened by or complaining about them, she approached them rather imaginatively. She disposed of difficulties in that she immediately made them into something else. Consoling carnations!

And now, having spoken so much about the uncertainties, it’s striking for me to see that, yes, in fact, there was one great certainty: no matter what type of design I came up with or wanted to make, I could always be certain that Pina and the dancers would put it to absolutely beautiful use… they would make it a part of their world as best as they possibly could. And to think of the freedom that such a certainty brought to the set designs… Maybe that’s another part of the symbiotic relationship: I always designed the sets for them and they freed me from them by taking them over.

The field of carnations also had another side effect… take Amsterdam for example. We put Nelken up there and on the day following the premiere, sitting in front of the theater, there were these loud stagehands - the kind with missing teeth and broken nose bones and big tattoos… nothing was as normal as it is nowadays. Anyway, they were sitting there in the sun and straightening pink carnations. On the street, along a canal! It was a wonderfully absurd sight to see: these men, who most people would be scared to run into on the street, sitting there and making pink carnations.

Wim Wenders: Were there wires in the flowers?

Peter Pabst: Yes, there is wire in each of them.

Wim Wenders: Did that pose a danger to the dancers?

Peter Pabst: Sure, it could have, but that remained highly unlikely. I thought a great deal about the floor from the earliest stages… so I ended up with a floor that I could stick the carnations into without them flying back out as soon as someone came in contact with them. The greater the number of loose flowers scattered about on the floor, the greater the danger of injury. Thus, the floor itself became a relatively complex creation: wooden panels with holes in them, under those a fibrous insulating material that was used for thermal and/or acoustic insulation in homes at the time.

Wim Wenders: That’s a somewhat softer material?

Peter Pabst: That’s right, it is a soft material. Today it’s most often made of foam, but back then you still got fiber insulating board. It was similar to pressed coconut fibers or something along those lines…

Wim Wenders: ...so sound dampers like those on your ceiling here?

Peter Pabst: Exactly. They serve two functions: first, the fibers held the flower stems very tightly, and, second, they made the floor anechoic, meaning that the wooden surface no longer came in contact with the stage floor and, as such, no longer made such a terrible banging sound…

Wim Wenders: Let’s move on to Auf dem Gebirge hat man ein Geschrei gehört (On The Mountain A Cry Was Heard) – what kind of “field” did you play with and on for that piece?

Peter Pabst: That, like so many of my ideas, came from a photo. I have to think…it could have been one by Diane Arbus though I’m not certain. Either way, I found a photo…all that was depicted was the edge of a forest, a pine forest in the mist. Earth and fog…heavy earth, a field that was raked over everyday… But then I thought, that’s not what it is…I added a slightly warped slope to the field that was hardly noticeable when one looked at it, but that nevertheless lent a new tension to the picture. From front to back, the surface rises 20 cm on the left hand side and 30 cm on the right hand side. The sloping curves into itself, but only minimally…it’s not visible, but it’s palpable.

Wim Wenders: For the dancers it was probably quite an incline though.

Peter Pabst: No, they barely noticed it. It’s only about a 2% incline. The normal gradient of a stage upon which dancers are able to dance with no problem is between 3 and 5.5%. Of course, people looked at me strangely, not understanding why I would want to build such a surface - a slanted area of such a large-scale that cannot even be seen. And it was a massive construction effort. But, the one time that I omitted it from a rehearsal because we were running short on time, I allowed the dirt to be shoveled directly on to the stage surface and it was as if someone had unexpectedly covered your ears. That’s what it felt like…so boring, so unsatisfying. It just didn’t work without the slanted surface…that was now clear to everyone involved. Still, it remained, in every respect, a difficult floor.

Wim Wenders: Did the dirt stick to the dancers’ feet?

Peter Pabst: Sometimes. We were always walking a thin line between keeping it wet enough so that it didn’t raise up dust and dry enough so that no one lost their balance or had mud sticking to their feet. In any case, it was challenging for the dancers because it’s an irregular surface. The larger clumps of dirt had to be both coarse and secured. You notice those beneath your feet quite plainly. And then…

Wim Wenders: Then you...

Peter Pabst: ...then, at some point, I began to play around with fog.

Wim Wenders: Yes, the fog. Let’s talk about the fog.

Peter Pabst: I’ll get there, but I want to do it in a roundabout fashion. In the 1970s, I did set and costume design for Peter Zadek’s production of Hamlet in Bochum. The production was taking place in a renovated factory building. It featured an exceedingly poetic Hamlet, though that poeticism was very raw and brittle. Magdalena Montezuma was playing the ghost of Hamlet’s father. All I did for her was simply set up a crate that had a golden Baroque mirror frame set up before it. Magdalena would sit on the crate in the frame and was the picture of Hamlet’s father. And whenever the ghost would appear, she would stand up and step out of the frame…and then I would be there with my fog machine and I made her a cloud. (laughs) That was her ghostly guise. She always moved about in a cloud while I hissed and sputtered at her side.

So I came to the idea because I sensed that Pina and Peter Zadek - both of whom incidentally liked each other and held the other in great esteem - were quite similar. In a certain manner of speaking, both always thought quite simply. That always had something to do with their honesty on the stage… never cheating. What that translates to is: except when the fog is made of tulle, a fog machine makes fog. There is a person, he has a machine, he pushes a button, and when he does that a stream of hissing vapor pours out of a nozzle. This vapor then becomes a cloud, spreads itself out, and eventually envelopes the people onstage in fog. And when that is what is happening, Pina thought the same thing that Zadek did: you should be able to see it as such!

For Pina - at least during the time when we worked together - there was never any interest hiding or concealing anything with the help of large-scale, technical efforts. The reality of what was happening on the stage was the truth of the stage. In Das Frühlingsopfer, when the dancers exhaust themselves so thoroughly that they are panting and sweating and then throw themselves into the peat moss on the stage, then they are “dirty.” It’s just like in Zadek’s Othello where I painted Ulrich Wildgruber black and once the white-skinned Eva Matthes, playing Desdemona, threw herself into his arms out of love, then she too became black. Neither Pina nor Zadek were worried that this would come off as unrefined. Luckily, a crucial part of our cooperation was unquestionably that, from the very start, we shared this carefree nature. Neither of us had to be refined, neither wanted to exaggerate, and neither of us were that interested in technology. I can work with it, but I don’t need it.

Wim Wenders: Who operated the fog machine then? The dancers themselves?

Peter Pabst: No, I was the one holding on to the fog machine most of the time. It was like a paintbrush for me and I painted the air with it, sometimes quite expressively…I veiled dancers and I frightened them, broke up dance lines with fog, they would vanish and emerge once again. It was great fun and resulted in some beautiful images…not to mention a continually shifting mood that could go from the absolutely romantic to the totally frightening and threateningly chaotic from one moment to the next.

Later on then, as the fog found its form, a colleague of mine from the props departments took over.

Wim Wenders: Two Cigarettes In The Dark. In that piece you created a house that, proportionally speaking, was an impossibility and that seemed to falling apart in every way imaginable. It was a really off-the-wall piece. What was that? Where did it come from?

Peter Pabst: It originated out of desperation. I felt at the time as if I had already picked every possible field clean. (laughs) It was as if floors had become totally unfamiliar to me in some way. I just couldn’t do another floor at that moment.

So I took to looking for a room…spoke with Pina about rooms. She understood that I didn’t want to - or couldn’t even - think about floors anymore, and she seemed to be in need of a room as well. I don’t know anymore what the impetus was there. Perhaps it was a picture of a museum space, thus the large windows. They are like display windows. During the time in which I was sketching the room, it became a kind of loony Hotel New Hampshire for me. The doors are to small or too big and you don’t know where they lead to… and the people within it are all a bit crazy or at least behave as if they are.

Wim Wenders: It seems to call on German Expressionism a bit because of the disproportionality of everything…

Peter Pabst: Yes, completely...

Wim Wenders: ... you can see it in the behavior of the people as well.

Was that the first time you used a projection? Those Super 8 images projected on the naked breasts of…I think it was Helena…

Peter Pabst: Yes, that was Helena. They had tried that out in rehearsal and Pina ended up keeping it in the piece.

Wim Wenders: For me, as best as I can remember, that was the first time that something was projected in Pina’s work.

Peter Pabst: Well, prior to that, Pina had shown the film of a birth on a small screen in Walzer. Plus, there was the duck film from Kontakthof.

But, returning to the room. I just started to build and this room is what turned up. I wanted to set up various landscapes outside of each of the window so that they became stages unto themselves.

Wim Wenders: And such strange steps…

Peter Pabst: The steps… they are, architecturally-speaking completely senseless, they lead uselessly to floors above and below. And outside of each window there are further sets: a jungle behind one, a desert with a cactus growing in it behind another, and on the left...

Wim Wenders: That looks to be an aquarium of sorts…

Peter Pabst: Behind the other window, on the left-hand side there, that was indeed an aquarium. In fact, there were three aquariums, which I filled with goldfish. That was somewhat complicated. I always picked the fish up from a breeder, each in its own plastic bag filled with water. Then I would have to set the bag in the aquarium and allow the water within it to slowly even out with the temperature in the aquarium. Only then could I let the fish out of their bags and know that they would be fine. I also, incidentally, learned during this process that wild fish are not the least bit shy. I was able to pet them! They weren’t yet familiar with people.

Later, Dominique Mercy joined the goldfish in the water wearing nothing but white underwear and flippers.

Wim Wenders: Nice. I quite enjoy swimming with fish as well. I have a friend who filled his swimming pool with fresh running water and there were fish in it so you always knew that there was no chlorine or anything of that sort in the water. The fish felt completely at home and were like dogs wagging their tails through the water…and they were always happy to have someone swimming with them…

Peter Pabst: ...they had formed a society then, you know, its not only dolphins that are that curious.

Wim Wenders: Tell me about Viktor. In that piece, anything and everything is brought out onto the stage. You could have decorated multiple stages with all of the things that were on that single stage. Are you also responsible for all of the props and the things that are brought out on the stage?

Peter Pabst: Basically, yes. But, that’s not to say that I invent or design every piece of furniture or every prop that is used. Marion Cito takes care of that in addition to wonderfully costuming our dancers.

Many of these things are already present in the early rehearsals. The dancers will often take care of getting props that they need for their various dance concepts from Jan Szito or Alf Eichholz, our two prop masters. That we have two prop masters in our relatively small company should tell you something about how important the procurement of materials for our pieces is to us. If the dancers want to try something out and need some sort of item to help in that process, then it has to be readily available, otherwise the moment is over before it can be had.

Oftentimes the props remain as they were during rehearsals. Sometimes though, I realize, that from an aesthetic or practical standpoint - or even in some instances for safety reasons - they could or should look different. If so, then I change them, begin to create… but normally time limitations play a role in this process. During the dress rehearsals for Viktor, Pina wanted to have a scene that looked like an auction… and something like that then has to take form in just a few minutes. So you really don’t have much time to think, well, how should this look?

I value that process highly, for me it is educational because it often leads to completely unpretentious solutions. As a designer, normally I wouldn’t think myself a person who would trust such solutions, but sometimes they are exactly what are needed in a given moment. Stepping in without a design idea in mind is very often more refreshing and livelier than the most beautiful design could ever be. In “Viktor”, that took the form of a rather crazed blending of antiques, banalities, and a number of other things…

Wim Wenders: ...an unbelievable amount of furniture.

Peter Pabst: Yes, a ton of furniture. Almost all of those pieces where taken from Die sieben Todsünden (The Seven Deadly Sins) because that was what was most readily accessible… and those also happened to be the only “good” pieces of furniture we had.

Wim Wenders: Used twice, right?

Peter Pabst: Our only options were always to either buy things new or make use of the materials we already had. Renting or borrowing didn’t work for us because we would essentially be kidnapping someone else’s pieces if we were to go on tour.

Wim Wenders: What was in the background there? As far as I remember they looked like pyramids, Incan constructions of sorts on the left and right. What were those things?

Peter Pabst: Where?

Wim Wenders: In Viktor, on both the left and right-hand sides there were these things that rose up from the floor… yes, what were those?

Peter Pabst: Oh, I never thought of them as buildings. They are walls of earth. I just never decided on what they actually were… Perhaps the whole stage was actually a giant pit. Maybe a world remains up above or perhaps reality is just down below. I never reached a definitive conclusion on that.

Wim Wenders: Oh, okay!

Peter Pabst: That was the first time that we did that sort of coproduction.

Wim Wenders: You introduced the concept of coproduction with that piece then?

Peter Pabst: Yes.

Wim Wenders: With the Romans!

Peter Pabst: I think some people in the audience were disappointed with the stage design because they expected broken columns or something like that. But that’s not what we had. It was just earth and overhead Jan Minarik was constantly going back and forth with a shovel. Before every performance, I had tons of dirt brought overhead so that he could be shoveling it onto the stage below for the next three and a half hours.

Wim Wenders: He must have really been slaving away.

Peter Pabst: Yes, that was an extremely labor intensive set design.

On the evening of the first day of technical setup everything looked terrible… the parts were all covered in scratches from being transported, it was noticeable that they were individual parts, white spots and crumbs all over the place. Terrible! It was enough to make you want to cry. I was horrified and indescribably disappointed. Realizing how disappointed I was, Pina modestly suggested I clear away some of it, cordon it off with red-and-white plastic tape and effectively convert it into a construction site. It was actually a rather brilliant idea. I responded quite virulently against it though because I wanted to finish the design properly first. And if she had continued to prefer it, then I would have happily organized her construction site.

The next day we took to improving the design with painstaking care and, in the end, I sprayed the entire thing with glue and threw fresh dirt against it. The result was stunning. The earth shimmered like brown velvet in the light. This extremely dark space was like a warm blanket enveloping the dancers. It protected them. Every time we assembled it thereafter, we would spray the whole construction down with glue again and throw fresh dirt against it. Just as you said: slaving away. It was madness! It was so much effort and so much earth that after 17 years the pieces could no longer be lifted because they were too heavy and we had to build the set anew. But, I think, the design deserved such meticulousness…and Pina’s piece deserved it even more. For me, Viktor remains one of the most multifaceted and richest pieces from Pina’s oeuvre. And this stage space that was created was not only filled with life, but the space itself lived at some point. A large space that is entirely clean at the beginning slowly but surely becomes overgrown… thanks especially to Jan who unrelentingly shoveled a vast amount of dirt from above onto the stage surface below.

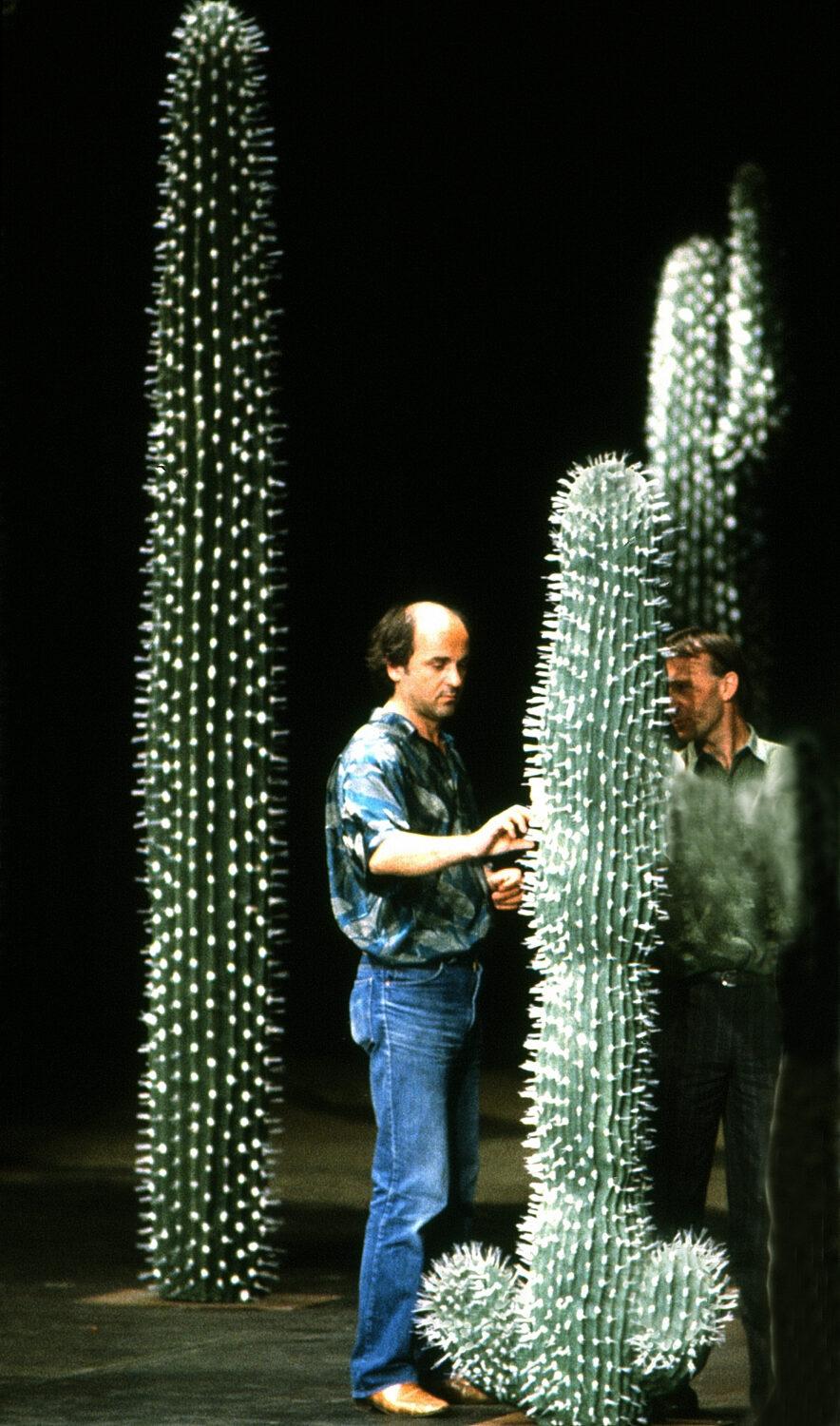

Wim Wenders: Thereafter, things were a bit off-the-wall, like with Ahnen and the cactuses that were on the stage. How did you make those?

Peter Pabst: I think I found a photo of some cactus-covered landscape, something that wasn’t especially nice, even a bit boring actually. Still, I really love large cactuses. I have always dreamed of one day having a house in the desert of Arizona, a simple house made of wood… but there would have to be at least three large cactuses standing in front of it. Anyhow, Pina liked the idea of cactuses onstage as well, but it was all a bit off kilter at first, at least when I began to make the models. I wondered how could I make miniature cactuses? Somehow, they needed to look as if they were alive. Sure, you can sit down and whittle them… carve them out, but then they always end up looking stiff. There is no possibility for irregularity. That’s one of the basic problems you face with such forms when working with small-scale models. I can’t properly imitate the properties of materials - flexibility, elasticity, mobility, exact weight, and surface structure - on a 1:25 scale. These pieces are almost always too thick, too heavy, too brittle, or too rigid. These pitfalls of working with model forms work against creating a model that is true to life. But still, I wanted “living” cactuses! I always thought of cactuses as figures, as people of sorts…

Wim Wenders: ... especially those with what look like bending arms.

Peter Pabst: ... they’re such representative things, aren’t they? In any case, Pina had just picked up some pastries from her favorite café. Café Best, just down on the corner, was a traditional café with its own bakery… and then it came to me. I went over and asked if I couldn’t have a pastry bag. Bakeries have these plastic piping bags, you know, that have metal tips on the end…

Wim Wenders: Sure...

Peter Pabst: ... and they use them to put those dabs of butter cream on their pastries.

Wim Wenders: ... and shortbread cookies!

Peter Pabst: That sums it up nicely! I simply mixed plaster instead of butter cream - it has the same consistency - and I used the pastry bag to “pipe out” cactuses. Then I just had to wait for them to harden.

Wim Wenders: ... for your model?

Peter Pabst: … for my model. Utterly life-like forms… Remembering them pleases me even now because it was such a naïve idea. That’s yet another topic worth discussing. Naivety is so important! You will end up closing so many doors if you approach everything professionally. Pina once said something that gets right to the heart to this point. She said, “For everything that you learn, you also lose something.”

So that is how the cactuses came into being, in the model at least, and I think, in this particular instance, we didn’t really hesitate…we were decided rather quickly. It should be a strange world. And it worked well because the most off-the-wall thing about the evening of the premiere was the piece itself in its entirety. And the fact that we made our decisions so quickly was also a good thing because I wanted to have 50-60 pieces, each between 4 and 6 meters high. And to have that, well, it was already - as often was the case - too late. But the design had to be strong… just like in Arizona…

Wim Wenders: Was that a coproduction as well?

Peter Pabst: No, just Wuppertal…

So anyway, the technical director and the workshop bristled and balked because of how close we were cutting it - as I said, this back-and-forth had become a tradition of sorts - until finally the manager of the workshop - at the time, Leo Haase - said, “If the first sketches are left with the porter by seven in the morning tomorrow, then I’ll get started.” So, overnight I drew three cacti as I thought they should look and the workshop produced samples from them. That way we were able to get a feel for them and discuss how they could be improved. Luckily enough though, the samples were so good that we were able to take them as they were. In the meantime then, I sketched the rest of them and the workshop made those additional 50 pieces for us.

Wim Wenders: From what type of material?

Peter Pabst: Wood, steel, Styrofoam, and laminated surfaces… classic theater materials. I have a very precise sense of sculptural forms… most of my set designs for Pina’s pieces are large-scale sculptures, that was the case with Viktor, Ahnen, O Dido, Wiesenland, Rough Cut, Ten Chi, and Vollmond. In each of these pieces I remained very conservative with regard to my choice of materials and technique. That has something to do with my sense of form and the way I design my molds, but also something to do with Herbert Rettig, a dear friend and wonderful set sculptor who helped make each of these pieces a reality.

Wim Wenders: Did the cactuses have spines?

Peter Pabst: Now there’s a “prickly” subject! Up to that point, they didn’t have any spines, but I always thought that that was stupid…

Wim Wenders: That’s what I would think...

Peter Pabst: ... a cactus without spines isn’t really a cactus at all. But what do you make cactus spines out of? So the search began. And this search in particular was another one of those wonderful Wuppertal experiences…

Wim Wenders: (laughs)

Peter Pabst: So many ugly things have been said about Wuppertal…it’s boring, bland, there is nothing going on and so on - maybe it appears as such at first glance - but behind that surface you always find something surprising. So I drove around and kept an eye out for something that could be transformed into cactus spines. Most of the time, Leo Hasse joined me in this quest. He knew all of Wuppertal’s hidden corners and he and I were good friends. In any case, at some point in our searching we came to this place. I wouldn’t even be able to find it today… it must have been on the other side of Tal heading toward Varresbeck or something. But there, beneath the trees, there was an old manufacturing hall and an office building, both very small. There was a woman in her late sixties there, wearing a floral print blouse with gray woolen gloves on - funny that I still remember that now, woolen gloves with the fingers cut out of them. The whole scene looked like something out of a film set in the 1930s. Two men came out from the warehouse and they were wearing these long gray coats, woolen gloves, and flat caps. They produced brooms to sweep the streets with there...

Wim Wenders: Ah ha!

Peter Pabst: I was, of course, interested in the material they were using for the bristles. And I was able to buy it from them directly as a raw material, a bundle about 1.5 meters long made out of nylon rods that were about 1-1.5 millimeters thick.

Wim Wenders: Earlier something like that would have been made of brushwood, right?

Peter Pabst: They were nylon bristles by now...

Wim Wenders: ... and you stuck them into the cacti.

Peter Pabst: Yes, but not right away. At first, these nylon bristles were so tough that I couldn’t even break them. I had to cut them into short pieces for the spines. And then as soon as I entered the workshop and mentioned the word spines, they were ready to declare me insane…I just missed out on being committed. They knew right away that we were talking about thousands upon thousands of spines. And, as usual, we were running short on time.

It was clear to me that only setting a precedent would help get the job done properly and on time. So I hid away one evening and allowed myself to be locked in the theater overnight. Then, I worked through the night and outfitted a cactus with the bristles…bored holes and then glued the spines into them.

Wim Wenders: You actually bored holes?

Peter Pabst: Well, no. I would just poke holes in the cactus and then stuck a small bundle of spines into it. I thought to myself, if there is a cactus with spines standing there when they walk in tomorrow morning, then there’s no turning back. And they got the message first thing at seven the next morning when they arrived. I’ve rarely raised such a racket in the theater. But then, sure enough, one of the most wonderful theater miracles I have seen in my life took place.

Wim Wenders: That doesn’t surprise me...

Peter Pabst: Well, word of the problem spread quickly and soon everyone was coming by to help. Not just the workmen either. Not only were there metalworkers, carpenters, painters, stage technicians, lighting technicians there, but people from the management and the script departments as well, all of them. If someone had twenty minutes to spare, they came by to help put spines in these cactuses. The whole theater shared the responsibility and little by little the cactuses grew more and more spiny. It was truly magical.

Wim Wenders: You must have guarded them jealously thereafter, these cactuses…

Peter Pabst: Yes, that’s another topic. I really wish that they were handled in a manner that reflected just how precious they were… how costly they were in both the literal and figurative sense of the word.

But, that is not where the story ends because soon enough I realized that these new bushes of spines were too straight…

Wim Wenders: Oh no! What now?

Peter Pabst: … they really didn’t look authentic. They were all parallel to one another and completely uniform. I thought about what else I could do to these cactuses and then I thought, I wonder if they’re sensitive to heat. Well, I got a hold of a superheated air fan, which is often used to remove varnish, and as soon as the hot air hit the spines they shot out in every direction.

Wim Wenders: Great.

Peter Pabst: So then I spent hours blow - drying - a hairdresser for cactuses, that’s me!

Wim Wenders: Somehow that makes perfect sense when considering the obliqueness of the piece.

Peter Pabst: Yes.

Wim Wenders: After that then, if we can move on to the next piece, there was an even bigger bang if you will. (laughs) It was another of these…

Peter Pabst: Which piece came next?

Wim Wenders: …seemingly impossible sets, this time because of the wall that collapses in it. Palermo Palermo: that must have been the piece where you were, once and for all, deemed insane.

Peter Pabst: Yes, well, in that piece the challenges faces were much more serious in nature.

Wim Wenders: Did you consider what you were going to do with the wall from a structural engineering point of view at first? How did you go about the whole thing? You can’t just topple a wall like that…

Peter Pabst: I don’t know if I’ve shared this before… it was the autumn of 1989.

Wim Wenders: Oh, well, of course, there were a few walls coming down at that time

Peter Pabst: Which proved problematic in some ways because there was no longer any way for us to make clear to people that our wall coming down had nothing to do with the one that fell in Berlin.

Wim Wenders: Sure.

Peter Pabst: It was really in the autumn of ’89! (laughs) But, we brought down our wall 14 days earlier.

That was yet another period of desperation. We weren’t coming up with anything. Pina was exasperated and so was I. I had already tried a number of things out for the new piece, among them an orchard in bloom. Everything was very pretty, but nothing more than that… and you always know when that’s the case…you feel when something isn’t there or when something isn’t the way it should be. Well, during a break between two rehearsals, Pina and I sat there alone in the Lichtburg - you know the Lichtburg, the former movie theater from back in the 1950s?

Wim Wenders: Okay, yes.

Peter Pabst: And as was the case with movie theaters in the fifties, the walls of the Lichtburg were covered with this sort of corrugated plastic film called Acella. Over time though this wall covering in the Lichtburg had been torn in certain places and you could see the bare masonry behind it. And in the midst of our silent despair, Pina turned to me with a timid smile and said, “Look at that, it looks like a wall behind a curtain.” Silence…maybe ten minutes of nothing… and then I said, “We could build a wall.” And after another ten minutes Pina asked, “How so?” Me: “We could wall up the stage portal.” Finally she said, “And how do we get rid it of after that?” And I thought about it and then, “We could knock it over.” Pina thought about it for a minute and then said, “You know, I don’t think I like it. When I think about the noise that Styrofoam makes when it falls… I don’t think I like it…” And then I said, “I mean a real wall…” And then came another of those long silences. After four, maybe five minutes Pina looked at me and said, “You’re crazy!”

Wim Wenders: Like a Beckett piece.

Peter Pabst: It was totally a Beckett piece…that was the birth of the wall in Palermo Palermo.

Wim Wenders: You don’t respond well to that, do you… someone refusing you something?

Peter Pabst: No, I don’t.

For the wall then, I first took to looking for the proper material, for stones with which I could not only build a wall in a reasonable amount of time, but for stones that would also allow me to do so safely so that it could be trusted when other people were near it on the stage. It was already clear to me that the wall could not be built of bricks…

Wim Wenders: Is this where you used the hollow blocks?

Peter Pabst: Yes, I used those in a few of my early attempts. I don’t actually have any experience in the area. I know nothing about stones, about their strength or about structural engineering. I just had to approach the whole task rather empirically: I purchased an assortment of stone and whenever we had rehearsals onstage I would just build a small wall backstage about three meters high… as high as I could get using a ladder. And when I was finished, I would shield my head and (laughs) push it over using my hand. I was always scared doing that; I worried that one would fall forward and land on my head. But having such a fear is also useful because it forces you to be continually cognizant of potential problems and possible ways of dealing with them.

During these early experiments, I was always looking to see how the stones compared with one another, how they bounced or if they broke, what kind of noise they made on impact, and how many of them remained intact. Doing this, eventually, I was able to discover my material.

Wim Wenders: Was that this material made of pressed pellets?

Peter Pabst: No, no it wasn’t Ytong. I experimented with Ytong because of how light and stable it is, for my purposes it didn’t have enough elasticity to it… using it resulted in too much breakage. So, I ended up using a different material, a hollow block as well, but one made of wood shavings pressed together and then soaked in cement. These blocks actually have positive and negative profiles on the sides, something that was especially important for my wall. It allowed them to interlock with one another. That meant that the wall stood securely even before cement was used on it and, thus, we were able to dispense with the cementing process entirely on the stage.

Wim Wenders: Were they lighter?

Peter Pabst: No, unfortunately they were a bit heavier than the others. The manufacturer produced a special line of products for me that included a larger proportion of cement, which translated to greater overall strength.

Wim Wenders: And how did you knock the wall over then?

Peter Pabst: Above all else the wall could not, under any circumstances, fall forward; therefore, the wall was held on both sides by stabilization brackets that made it impossible for anyone to push over. It was too strong and stable for that anyway. In the end then we used a wince to pull the wall down from behind. Two engineers stationed below the stage were responsible for that. In order to have greater control over the falling wall, a sophisticated system for distributing the pulling force across the entire wall was developed. And the engineers below were given earplugs.

Wim Wenders: It made quite a lot of noise I imagine. And did a structural engineer check it out to make sure that nothing…

Peter Pabst: All of them said no; I’ll never forget that. The first time that we built up the wall, all of them were really standing right there: the theater’s engineering supervisors, the union representatives, the personnel committee, a representative from the municipal building department, and so on and so forth. It was unbelievable. They were all on the stage and said no. It was a very lonely day for me. I was somehow there, all alone saying “yes” while everyone else was saying “no.” In the end, we reached an agreement and I built the wall up until it reached its maximum - and somewhat menacing - height. During that evening’s rehearsal, I asked Pina if we should knock it over. And she said yes.

Wim Wenders: I bet that raised your blood pressure a bit?

Peter Pabst: I was on the brink of having a heart attack. (laughs) My God, did it ever raise my blood pressure! The problem in such situations is that I can always only hope that I have thought through everything precisely enough. I don’t have any experiential or empirical information to work from and no one could really help me be certain. But that’s also very satisfying.

I’ve often thought about why I have so much fun doing what I do… discrediting others’ reservations and discovering technical solutions for and by myself.

I think, in my mind, I draw a distinction between two aspects of my work as a stage designer. There is, first and foremost, the artistic aspect, the concept, which I most often draw from my own gut instinct. If I already began to think about the technical consequences in the midst of this early phase, then I would be utterly dismayed, so much so that I would no longer have the courage necessary to dream. To conceive of and design something, your fantasies must be allowed to run free. I enjoy that. Also, during this phase, I would often promise Pina anything and everything under the sun, without knowing if or how whatever I’ve promised was even possible. Pina and I were nearly identical in this regard. She always invented in an uninhibited fashion, without knowing how everything should or would eventually fit together. Somehow we both always managed to position ourselves with our backs up against the wall. That is what is required, I think, in order to generate the drive one needs to realize something that seems impossible. And for that I have to use my head. It wants to do something too, needs to do something.

I have absolutely no training in things technical, mechanical, or physical. When I was younger, I couldn’t even grasp such things. I didn’t even finish my Abitur (comprehensive examinations at the end of secondary school in Germany). I left school because I just couldn’t understand scientific subjects… not math, not physics, not chemistry. This mental block finally came to end much later. Today, I take great joy in this kind of logical thinking. I realized at some point that I actually didn’t need to know all that much. I just had to observe everything closely and think logically. If you do that, than you can precisely analyze any problem. And as soon as you understand what is situated at the heart of a problem, then you also end up discovering precisely how you can begin to resolve it.

Wim Wenders: I’m familiar with that from my film work. It basically comes down to you figuring out why something in particular doesn’t work…

Peter Pabst: So that you can do it anyway.

Wim Wenders: It’s the same in theater then?

Peter Pabst: Exactly the same.

Wim Wenders: Well in Palermo Palermo there is actually something that was unusual for Pina’s work, I believe: a curtain.

Peter Pabst: Yes, it’s the only piece that uses a curtain and only does so because of the wall.

Wim Wenders: Why did you want to have the curtain there?

Peter Pabst: Because we wanted to have a wall behind a curtain. (laughs) That way the audience wouldn’t see it right away. That was how we first envisioned it when the idea was born at the Lichtburg.

Wim Wenders: Ah, okay.

Peter Pabst: We afforded ourselves the luxury and the pathos of the rising curtain. That is always, in a certain way, a ritualistic sort of moment in the theater - the curtain is rising! It signals that a world is about to be unveiled and a story is about to begin. But, in Palermo Palermo, the curtain went up and nothing began. The stage was walled up!

Wim Wenders: Yet the curtain maintained that pathos nonetheless?

Peter Pabst: Yes.

Wim Wenders: And were there curtains present in any of Pina’s other pieces?

Peter Pabst: No, none as far as I can remember.

Wim Wenders: And the dog? There was a dog in the piece as well, wasn’t there? What kind was it?

Peter Pabst: Well, originally that was Jean’s dog, Jean Sasportes. He had a dog that he called Truia. Jean also had a motorcycle - a Honda 750 - and was from Morocco. And on the front of the motorcycle, on the tank, there was a pillow and a folded blanket fastened to it and…

Wim Wenders: ...that’s where the dog rode.

Peter Pabst: Exactly, Jean would sit on his motorcycle, whistle, and Truia would jump up and sit on this blanket. And that’s how they would ride together, even all the way to Morocco. That dog was unbelievable! It was completely insane and played that part in Palermo Palermo at first.

Wim Wenders: And he took direction well?

Peter Pabst: He took stage directions well, liked to eat and loved Jean!

Wim Wenders: In the next piece you returned to a field, but this time one covered in snow. What kind of field was that?

Peter Pabst: That was a dream of mine for some time. Now we’re returning to the topic of floors because, well, this is actually a story about the flooring.

Wim Wenders: Well, we left the topic for a while and now, I guess, it’s about time we turn back to it.

Peter Pabst: It belongs to a set of images that had been running through my head for years. I had wanted to create a winter landscape for quite some time, and I was always playing around and getting crafty with the idea, but somehow it never turned into anything, possibly due to the fact that I didn’t know what I should make such a wintery scene out of.

And then, at some point, I thought to myself: salt! I bought some salt at the grocery store, allowed it to “snow” all over my model box… and it turned out good. It was obvious, however, that I couldn’t very well use normal table salt. It’s an aggressive substance that would begin to rust all of the machinery on the stage almost immediately. If that were to happen, I would surely be banned from the building. But an even bigger problem still was the dancers. In so many of our pieces they dance barefoot and their feet are so often in bad shape. And I was going to pour salt on their wounds…that would just be mean. But, I found some neutral salt at the pharmacy that wasn’t corrosive: Epsom salt. You can buy it in these 100g packages and its meant to help with digestion…

Wim Wenders: Is it similar to Glauber salt? You can take it to clean yourself out as well. And it’s easy on the stomach.

Peter Pabst: It’s similar.

Wim Wenders: So, the floor was covered in Epsom salt. Is that something only available at the pharmacy?

Peter Pabst: No, I don’t think so. It’s just very expensive.

I ate some before using it in order to see what it would do to my stomach, if it would give me diarrhea. Because, well, the dancers were going to be rolling around in it, and they could very easily swallow some of it, and then all of them would have a problem on their hands. Nothing happened to me though. And from there I just had to trace the route back from the pharmacy to the saltworks so that I could find some at an affordable bulk price. According to my calculations, it was going to take about ten tons of salt to fill the area beneath the dancers’ feet. And thus, the snowy landscape came to be. It was beautiful because of the way in which the salt glistened like fresh snow does in the sunlight. And fresh snow crunches beneath your feet, something that the salt did as well. All of it came together perfectly.

Wim Wenders: And it fell directly on to the dance floor from above?

Peter Pabst: It was spread about on the dance floor, yes.

So, the wintery scene was there, but there were still so many other images that Pina liked as well. I had already given thought to the salt crystals and to the fact that many projection surfaces are crystalline. But Pina and projections, those two things just didn’t go together at the time.

Then, one time, she said to me very sadly, “It’s a shame that we can’t make use of more images, but we can’t very well reconstruct the stage each time we want to create a new picture.” And at that moment, (laughs) after making my apologies up front, I very carefully asked if she could ever envision projecting images. And she said that she could. That was the real beginning of projecting in Tanztheater.

The use of projections made the wintry scene colorful and sometimes made it feel completely like a fairy tale; and yet it also maintained a sense of absurdity to it. Salt was made into sand; a snowy patch into a desert… and sometimes flowers even bloomed there. And then it was winter once again. Dancers ran about in colorful summer dresses through a tropical forest and, just a few meters away, Dominique Mercy froze between snow-covered birch trees.

Wim Wenders: So, essentially they were acting upon a screen.

Peter Pabst: You’re totally right. I actually never thought about it like that, but that’s exactly what it was.

Wim Wenders: So that was the beginning of your extended period of working with projection.

Directly thereafter though you moved from a snow-covered landscape to a moonscape, only there was a regular ship stranded there rather than a spaceship.

Peter Pabst: Didn’t that come earlier?

Wim Wenders: Das Stück mit dem Schiff (The Piece With The Ship) immediately followed the last one we discussed, I think.