Remembering Pina - with Michael Morris and Alistair Spalding

Former co-director of Artangel Michael Morris and Artistic Director and Co-Chief Executive of Sadler’s Wells Alistair Spalding reminisced about their late friend.

Michael Morris and Alistair Spalding in front of the Sadler's Wells Theater in London in February 2005

Podcast

Transcript

Caroline Issa: To mark 15 years since the death of the German choreographer Pina Bausch, TANK has produced a special podcast in which Michael Morris, UK Producer of Tanztheater Wuppertal from 1992 to 2012, and Sir Alistair Spalding, Director of Sadler's Wells, the company's long-standing London home, reflect on their close relationship with the legendary choreographer.

Michael Morris: Today I'm joined by Sir Alistair Spalding, Artistic Director and CEO of Sadler's Wells. We're going to be talking about the choreographer Pina Bausch, with whom I worked for two decades prior to her sudden death in June 2009 at the age of 69. Alistair, thank you for joining me. I've lost count of the number of times we've visited Wuppertal together over the years and thanks to those trips, the exceptional international dancers of Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch have been regular visitors to Sadler's Wells Theatre since it was rebuilt in 1999. Should we go back a little bit further than that?

Alistair Spalding: Yes, well, you can because I wasn't there. You started much earlier with the company.

"My addiction with Pina started in 1982 at the old Sadler's Wells which, if you remember, the whole building was probably half the size of the stage now."

Michael Morris

Michael Morris: It became a sort of addiction, as I think it does to everyone who sees the company. My addiction with Pina started in 1982 at the old Sadler's Wells which, if you remember, the whole building was probably half the size of the stages now. It was tiny. Looking back on it, it was a miracle that Pina Bausch got her two shows. One was called 1980, which was a very significant year for her as we'll probably talk about, and the other was called Kontakthof which means in English ‘contact yard’. Channel Four were filming it. It was the early days of Channel Four, and Michael Kustow, who was the first Commissioning Editor of the Arts, decided to film it, which helped to fund the presentation. If you talk to people about 1982 now, they claim that half the audience walked out. I saw it three nights running, and that really wasn't the case. People were gripped. I had never seen anything like it. I didn't know that this existed, this work that combined so many elements of human experience. I was just completely thunderstruck. When did you first see Pina’s work?

Alistair Spalding: Well, I think it must have been 1996. Oh, no, actually, it was when the company finally came to London.

Michael Morris: Viktor, in 1999.

Alistair Spalding: Yeah. Going back to that moment in 1982, what happened was, as far as I understand it, lots of people from the theatre world came to those performances, and it made a huge impact on the theatre profession as well as the dance profession.

Michael Morris: Yes. I've never seen an audience that combined people from the visual arts, the theatre, music and across the board, really. But what you got after Pina Bausch had been to London was a load of shows at Riverside Studios and the ICA that featured chairs on stage. Now, there are companies that I see in different parts of the world who don't even know they're influenced by Pina Bausch.

Alistair Spalding: Just going back to 1982. There's another story I've heard was that there was an issue with the musicians union because there was music in the show, and at the time, you had to use musicians. They put a string quartet in the foyer or the tent or something.

Michael Morris: Pina always used tape for the soundtracks for her shows, not to cut corners, but she liked the kind of feeling of the past that a crackling recording evoked. That wasn't good enough for the musicians’ union. So the way it was solved was that a string quartet played in the lobby, so that the musicians were paid, even though they weren't paid to perform the soundtrack for the show.

Alistair Spalding: I often wonder what they played.

Michael Morris: I can't remember. We thought they were buskers at the time. We weren't sure what they were doing there. The show was about three hours long. It featured a real lawn with a stuffed deer. And I'd never seen a piece of theatre – it was theatre, really – that was drawing on the performers’ own emotional and family histories. The performers collaborated with Pina, she just used to ask them questions. And they answered sometimes in words, and sometimes by movement. And she edited all this footage together into these amazingly structured works.

Alistair Spalding: Yeah, it was absolutely a new way of working, this ‘Tanztheater’ they called it, starting it with the performers, not having a narrative at all, but a kind of narrative which comes from them. And then scenes, which are just sort of like little vignettes, really. There are many of them through the pieces, and sometimes they don't make sense until you get to the end of the piece

Michael Morris: They have a sort of logic of a dream, really.

Alistair Spalding: They do.

Michael Morris: You go into a dream state. She really drew on the unconscious memories of her performers. I remember when I kind of stalked her for about five years because I was determined to work with her. And it took about five years before I found somebody who would introduce me to her so I could pop the question: “Why haven't you been in London since 1982?” The first time I met her was through someone who mentored me, a guy called Harvey Lichtenstein from BAM, Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York, who presented Pina’s work in the way that Sadler's Wells now does every couple of years. And I met her. And as you remembered, she wasn't somebody who made it easy for you to talk to her.

Alistair Spalding: She never talked. Only once did she ever explain anything in her work.

Michael Morris: She just didn't explain to the dancers either. She never explained it to press or anyone. But I said to her, “Pina I realise that you were born in 1940 in North Rhine Westphalia, in Solingen, which was being bombed between 1940 and 1945. When you were five, do you remember the bombs?” And she said, “Well, I was in a shelter in my parents' café – they owned a café – and all the neighbours would come. When the bombs came, we’d go down to the cellar, and I'd hide under the table. And I’d peep out at the adults between the folds of the tablecloth, and I'd see them getting drunk, I’d see them behaving like children.” I said, “Well, that's where your work comes from.” And she said, “I don't think so. I don't think it's got anything to do with my childhood.” So I realised that I should have never really mention it again …,

Alistair Spalding: But it definitely did, didn’t it? The piece that came out of that particular scene is Café Müller, which is one of the earliest pieces I saw as well.

Michael Morris: That was the first piece that I was involved in presenting. We decided to go to Edinburgh to make the appetite in London even more intense. So we went to Edinburgh with Café Müller, which is a piece which takes place in a café, revolving doors, and Pina herself is in the show, and she plays a blind dancer, who is sleepwalking through the café and the rest of the company are trying to move chairs and tables frantically so that she doesn't trip up. And it's all played out to Purcell's Dido and Aeneas. It's very, very beautiful.

Alistair Spalding: It is. Going back to that thing about the subconscious, it's the one which is most dreamlike. It is a dream.

Michael Morris: It is a dream. It's a dream of a dancer who can't see. She never performed it on its own. It's usually, as you know, done in a double bill with The Rite of Spring, but we couldn't afford The Rite of Spring. So we just did Café Müller which was 50 minutes, ideal for a festival. And it was very successful. People came up from London to see it which the Edinburgh Festival loved because they're always wanting to do things that you can't see in London. And it was a great event. We went to cèilidhs in the evening, Pina very proudly went shopping down the Royal Mile and said she found the only black kilt on the Royal Mile. I've got some wonderful photographs of her dancing ‘The Dashing White Sergeant’ and ‘Strip the Willow’. It was just wonderful. And she loved being in Edinburgh. She was very funny as well.

Alistair Spalding: She was very funny. And very sociable as well.

Michael Morris: Very. Once you relaxed with her and realised that she didn't really want to talk about her work, she’d talk about anything. Yes. Yeah. That was really sort of crossing the line.

Alistair Spalding: So we've just seen Café Müller again. And the point is, you said people loved it, it is still quite hard work. I mean, it's not an easy experience. It's so amazing that even now, it looks so out-there as theatre. And yet, this is like 30 years on, 40 years on from the …

Michael Morris: Almost 50 years. It was the mid-seventies.

Alistair Spalding: So how it was received then, obviously it was difficult in those early days going back to when she started at Wuppertal, people really did walk out, you know,

Michael Morris: They walked out, they slammed the door, they shouted, they spat at her in the street. I mean, it was shocking. Now, the reverence! You can't get tickets. She stuck to what she wanted to say about humanity. And I think what she wanted to say was actually not very easy to accept. She was not an intellectual, she never read Carl Jung. She wanted to reflect the dark side of humanity as well as the joy, and the piece is a great combination between the delight in being human and the fact that we're all going to die.

Alistair Spalding: Going back to those early pieces and you're saying this sense of the darkness as well, I think it did come out at that time in post-war Germany. Anselm Kiefer, Günter Grass, all these artists were dealing with this issue. And she dealt with it, I think, in her own way, not in a political way, but there were things going on there which probably came from a bit of trauma in that time.

Michael Morris: I’m sure that's right. It's something that hasn't been written about much in Germany, apart from by the great writer W.G. Sebald, who was a German writer who wrote in German in England, he was attached to the University of Norwich, not known so much in Germany. But he wrote about the aftermath of the war in North Rhine Westphalia when the place was flattened, unnecessarily, by the British and the Americans. That must have been terrible trauma.

Alistair Spalding: Yeah, yes. And also the guilt of what had happened the generation before and all those things. Not many people speak about that, but I think that was a big influence, I think. Pina would never, ever discuss that, of course.

Michael Morris: Everything was implicit. There was never any explicit criticism. The reason the works stand the test of time is there's nothing dated about them, because she never talked about contemporary politics.

Alistair Spalding: No no. That's right.

Michael Morris: It was always general observations about humanity that were true in the 1970s as they are now. There's something fundamental about the way humans behave, that doesn't change, and she understood that.

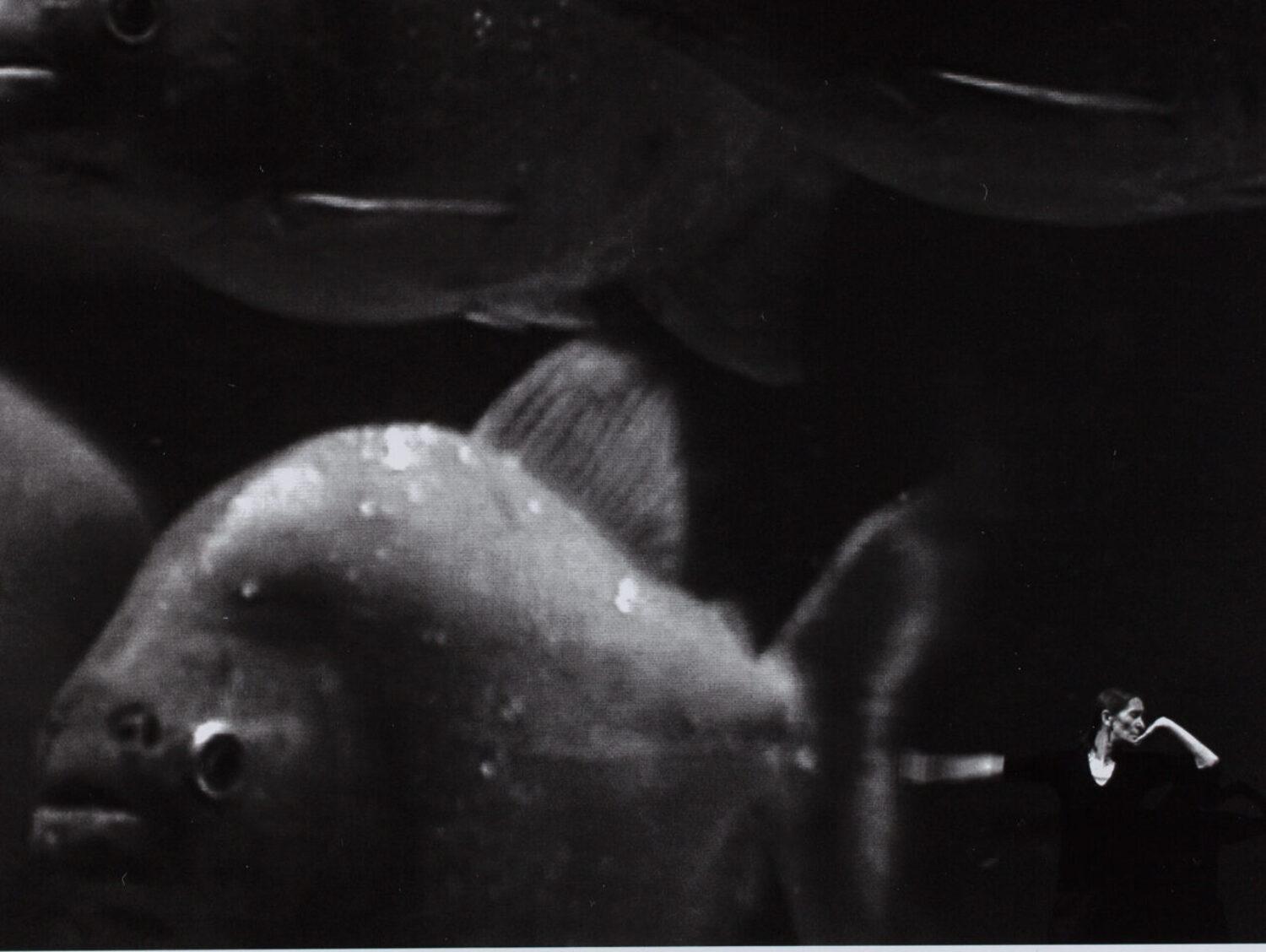

Pina Bausch and Michael Morris

Photo: Private

Alistair Spalding: So just going back to the chronology. So then, how many times did you present the company in Edinburgh after that?

Michael Morris: Three. We did Nelken, and then we did Iphigenie, which is a piece with an orchestra and singers, one of the pure choreographic pieces that she did. Café Müller and Nelken were just theatrical pieces. We wanted to show what a great choreographer she was. In fact, actually, in 1976, John Drummond, the director of the Edinburgh Festival then - I was far too young to have heard of Pina Bausch - but she came and presented The Rite of Spring. And credit should be given to that early understanding of her talent, because The Rite of Spring has been done over and over again. And it's still the greatest piece of choreography I've ever seen.

Alistair Spalding: Yeah, no, it is, particularly to that score.

Michael Morris: The Stravinsky score, which in itself was ahead of its time and when it was presented in Paris, I think the Garnier people walked out.

Alistair Spalding: It caused a riot, famously.

Michael Morris: Yeah. But then it was time to come to London, and we were waiting for the Sadler's Wells Theatre to be rebuilt so the stage was big enough to fit the company. So in 1999, she came with a piece called Viktor.

Alistair Spalding: That's where I came in.

Michael Morris: Which was amazing. We did something during Viktor which we tried to do every time she came, which was to, in the daytime, introduce her to other artists. Somewhere there's a videotape of her in Sadler's Wells mezzanine, talking to young visual artists, young musicians, just interested and intrigued and curious to hear what it's like for them. I think Fiona Shaw, who lived down the road from Sadler's Wells hosted a party where there was people like Alan Rickman, Antony Gormley, Simon McBurney, lots of people who watched Pina’s work, but had never met her. Katie Mitchell I think was there. And it was a wonderful time. She loved the sort of socialising after the show.

Alistair Spalding: She certainly did.

Michael Morris: There was always a good glass of red wine.

Alistair Spalding: We were always exhausted by the end of the seasons, because we would be somewhere else at 4am each night. The most famous occasion I remember is when we were at the German ambassador's residence and she stayed and stayed and stayed. Everyone was gradually leaving and the ambassador actually came downstairs in his coat because he had to walk his dog. And she said, “I'm terribly sorry, I didn't realise we were here so late”. She had a great energy.

Michael Morris: She had incredible stamina, she was always the last one to leave the table. My memories of her will be those kinds of moments, where she was quite childlike, quite mischievous, which you see in the work as well.

"We were always exhausted by the end of the seasons, because we would be somewhere else at 4am each night."

Alistair Spalting

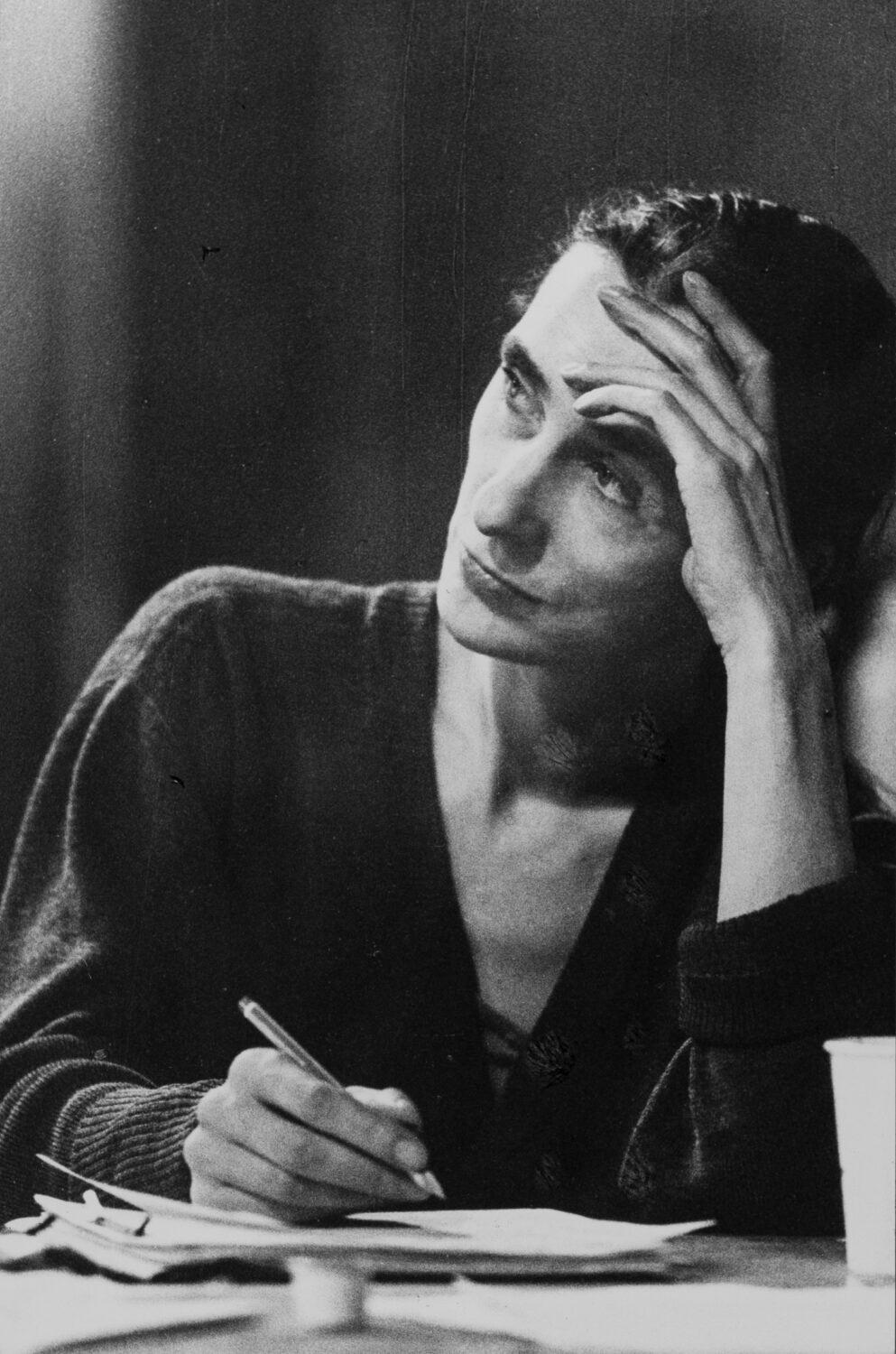

Pina Bausch and Alistair Spalding

Alistair Spalding: Just keeping to the chronology though. We did present every year around the springtime, but we then talked to Pina because we were coming up to the Olympics in London 2012. We approached Pina with a couple of ideas.

Michael Morris: In Paris, at that café that she used to like.

Alistair Spalding: Awful café with terrible food.

Michael Morris: Awful café but she loved it. We talked to her about the Olympics, in relation to international co-productions that she'd made with different world cities. I think the first one was probably Palermo. What the company used to do is they’d go to a city for three weeks at the invitation of the hosts who were co-producing. They would soak in the atmosphere of the city, they’d go back to Wuppertal, and make a piece that was sort of inspired by the experience. But these were very far from travelogues. Unless you knew that it was Palermo, and the title, Palermo Palermo - it was to do with the Palermo that existed in her mind, the eternal Palermo.

Alistair Spalding: It did have some connection though. That particular piece, what happens is at the very beginning, there's a wall that covers the proscenium and everyone's sitting waiting for the show to happen, and gradually they see that the wall starts to fall down. There's this incredible explosion of concrete and stone. And then you get this layering on the stage of all this rubbish and the dancers continue to perform. That's what it's like in Palermo because everything's falling apart.

Michael Morris: Including when she premiered in Palermo, the wall falling down actually broke the stage. And also in Palermo, you quite often see people wheeling strange shopping trolleys. I once saw someone wheeling a shopping trolley full of alarm clocks. And there's quite a bit of that, this kind of incongruity and surrealism in the Palermo piece. I think that we chose ten pieces that would exist …

Alistair Spalding: No no, but you're losing the chronology here, so we made one suggestion …

Michael Morris: We did make one suggestion.

Alistair Spalding: About the co-production.

Michael Morris: Africa?

Alistair Spalding: Yeah. There’d been all these co-productions from mostly European countries but from Chile as well, later on. There’d never been an African co-production. So we said well we would fund it, so we would make sure that they would go to somewhere, and there's this place called École des Sables in Senegal, and Germaine Acogny runs it, and we said that they can be the host, so we were going to go to Senegal that Autumn.

Michael Morris: To Dakar, that's right.

Alistair Spalding: And Pina then started not feeling so well. I don't think it was connected to the eventual reason for her death but she wasn't so great. So she said she couldn't go. And then we met her again. And she said instead of that, you should bring all the co-productions …

Michael Morris: It was her idea, I'd forgotten that. Bring all the co-productions. And I think she'd never thought it would happen. But it was the last project before she died that we actually plotted together with her. And there was something very special about the success of it because it sort of shuttled between Sadler's Wells and the Barbican. When Sadler's Wells were setting up for the next co-production, the Barbican was presenting another one. So it was kind of mad.

Alistair Spalding: It was huge. There were 50 trucks of material crossing from us to Wuppertal. We would never be able to do that now with the climate change issues. But we did it at the time. And it was incredible. It was the most extraordinary thing, absolutely exhausting. But as you say it happened after Pina died. So it felt like a real strong legacy moment.

Michael Morris: It was three years after she died.

Alistair Spalding: When I heard about her death, actually, I was in Montpellier, at the dance festival there and, and Bill Forsyth, another great choreographer, rang me in my hotel room and said that Pina had just died. I didn't realise up until that point how much she meant to me actually, in those years, she became a friend. That's really a wonderful thing. Someone that you looked up to as some kind of God, then you start to get to know personally and build a relationship - we did, didn't we?

Michael Morris: We did. She died so quickly that there was no chance for us to say our goodbyes. The company were away in Poland. She said, I think at the weekend when they left, she said that she wouldn't come with them, she wasn't feeling great. And she was admitted to hospital the same day and she died two days later. So there wasn't a long illness. She hated getting the checkups. She smoked like a chimney. Famously in Los Angeles, they created some sort of spacesuit for her so she could smoke in the auditorium while she was doing the lighting session, she was like in a sort of bubble.

Alistair Spalding: She also had a little incident when she was at Sadler's Wells once, it turned out that she was anaemic. We had to take her to a private hospital and she spent a couple of days there. She luckily had a balcony and she wheeled her drip onto the balcony to smoke and she would say to us, “Just make sure the nurses aren't coming”. She just couldn't stop, she was a champion smoker.

Michael Morris: She was extraordinary, I've never know anyone who smoked as much as Pina. It was like a sixth digit on her hand.

Alistair Spalding: It was yes. It was literally chain smoking.

Michael Morris: It actually almost made me want to take up smoking...

The meals that you and I would have with Pina, some of the companies used to come along, some others used to come along. Those will be my memories, not so much what happened on stage, but what happened offstage, and thank you for all those years of travel.

Alistair Spalding: It's been a pleasure hasn't it?

Michael Morris: It's been a hugely important part of my life, actually.