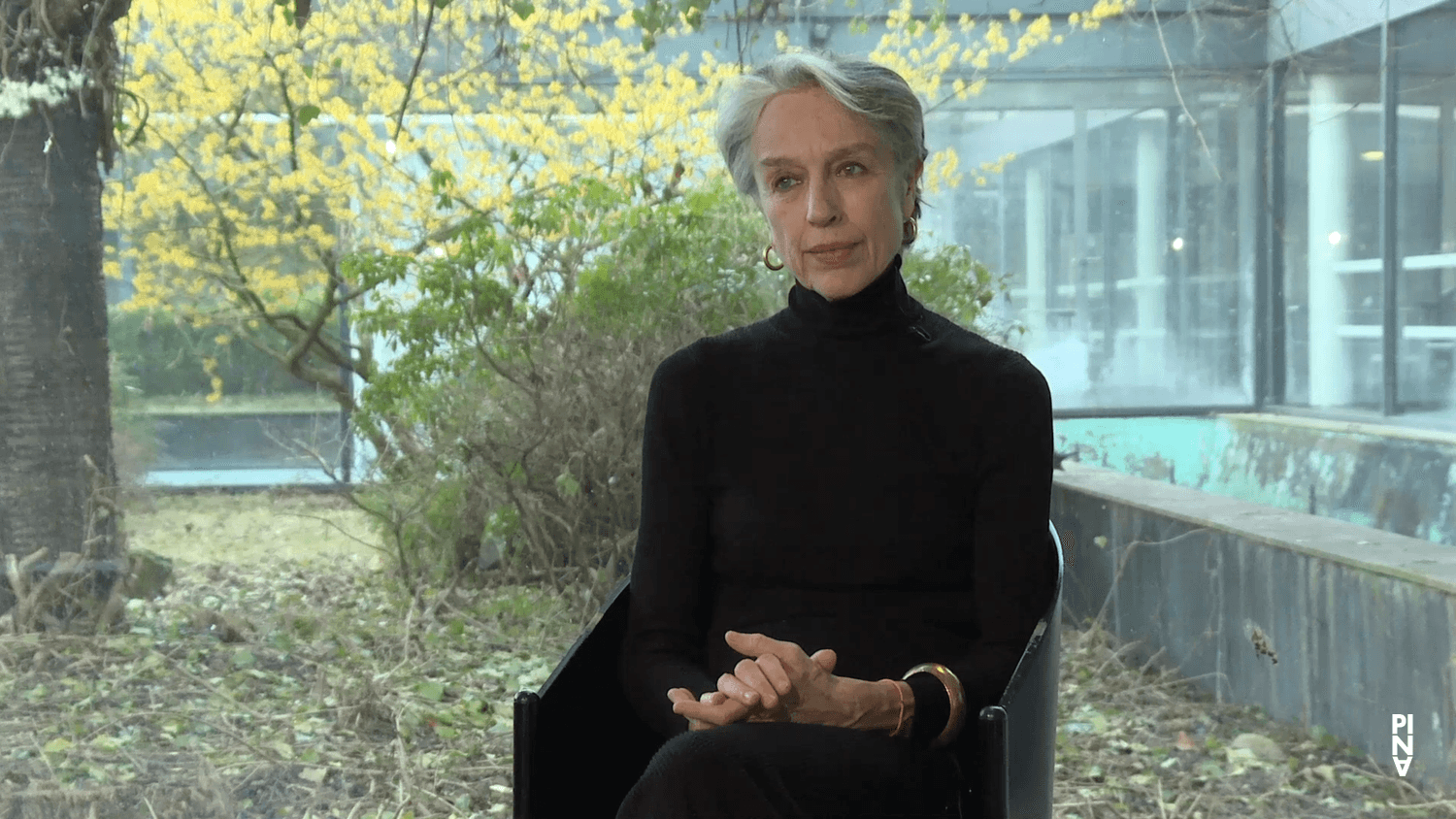

Interview with Finola Cronin, 17/8/2018 (1/2)

In her biographical interview, Finola Cronin talks about her dance studies, and how the political upheavals in Ireland permeated many decisions, notably if she’d study Ballet or Traditional Irish Dance. Moving to London, she deepened her knowledge of modern dance, and started her professional career, eventually working as a dancer with Vivienne Newport’s company in Frankfurt, subsequently for the Tanztheater Wuppertal. Today she is a theater scholar. Her memories are combined with reflections about basic principles that underlie Pina Bausch’s work.

Interview conducted in English

| Interviewee | Finola Cronin |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Camera operator | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20180817_83_0001

Table of contents

Chapter 1.1

Dance in IrelandRicardo Viviani:

If you would tell us something about your dance background.

Finola Cronin:

OK, my dance background. We could go very far back, because my mother had this idea that she wanted me to be able to take ballet classes. Now there is an interesting background to that in Ireland because ballet was considered something that was quite foreign, and traditional Irish dance was something that was often, let’s say, pushed on the children in school, but ballet was something that you really needed money to learn, because they were private teachers. And in some ways also, maybe it might indicate in a very casual, informal way, your ideas as to whether or not you might be quite republican, in terms of nationalism in Ireland, or whether you might have this eye towards the outside, towards imperial ideas of ballet. These are things that obviously later in Ireland, with the troubles in Northern Ireland, became very contentious, between republicanism – nationalism – and those who are unionist and so on, and that’s a legacy in Ireland that we continue to have, in this day and age. Anyway…

Rolling back a little bit: I would began maybe in the mid-60s to dance with a local teacher and learned the syllabus of the Royal Academy of Dancing, and I loved… It seemed to me the only thing I could do well. Really, because I was a good enough student at school, but I wasn’t a great student. So, I loved dancing, I loved putting on music and I would dance endlessly. We had a kind of conservatory at the back of the house, and I would dance there endlessly, put on music, put on records and just dance and dance and dance. So I studied, I suppose the basic rudiments of classical ballet for… maybe until I was about 14. A strange thing was then in Ireland, because we didn’t have any further education available to study dance professionally, so normally the route might have been… And what happened for example in the United Kingdom, which of course is right next door to Ireland, is that the students would audition for the Royal Ballet School, and then go at the age of 12, leave their parents and go in and become boarders in the various schools for young students to become ballerinas and to join the Royal Ballet Company and so on. So I felt really at the age of 14 or 15 that I’d missed my chance to be a dancer. So there was already a sense of loss about wanting to dance, but yet not having the ability in Ireland to study professionally.

I continued to dance however, continued to learn classical ballet, and then by chance I met a teacher who came to Ireland who had studied with Martha Graham. Her name was Thérèse Nelson. So this opened up a whole new door for, not only me but for many dancers of that period in Ireland, because of course it was possible to study contemporary dance at a later age. One didn’t need to have this extraordinary technique already polished by the age of 18. That opened this door for my ambition. I worked then in Dublin with Thérèse Nelson briefly and then with a woman called Joan Davis who was really instrumental in developing contemporary dance as an art form in Ireland. And she continues to work today, a little adjacent, in the area of body-mind-centering and so on. And she was someone who was hugely instrumental because she brought me – she sponsored me to go – to London, to the London School of Contemporary Dance for weekend courses, first of all. So that was my first connection with professional contemporary dance. The school and then of course the London Contemporary Dance Company.

So in 1978 I went to London Contemporary Dance School, and that’s what really opened the door for me to contemporary dance. But this was American led, if you like. This was the school that Martha Graham had established through Robert Cohen. My teachers were extraordinary. I had Jane Dudley, who was of course an original member of Martha Graham’s company – she was my basic teacher in first year – Noemi Lapzeson, also a company member, Juliet Fisher, Bill Louther, extraordinary dancers… Nina Fonaroff was there with a teacher of choreography. And these were extraordinary classes, we would always have live accompaniment music. It was so exciting! It was hugely exciting! And working with Jane Dudley was just phenomenal. She was really an extraordinary teacher.

Subsequent to that, I didn’t stay very long in the school. I felt I was old enough that I needed to move on, and I then worked intensively with a woman called Maria Fay, who was a Hungarian ballet mistress, and whose classes, a highly technical classic ballet… If you like, I sort of went back to classical ballet, and decided that I probably wouldn’t get a job sitting on my arse, on my bottom all day as you do in Martha Graham’s work, and felt I really needed to get up and start using my legs and arms much more, so hence Maria Fay’s work was really interesting and her classes were like performances. She herself performed her classes and had the most extraordinary technique, Russian technique. Very exciting people would come to these classes, and this was all in London then, in the open class system, so you never knew who you were going to meet in class, or see; the stars of the Royal Ballet would come to her classes and so on, so this was inspirational. So that was the beginning of my training.

Chapter 1.2

Entering professional lifeRicardo Viviani:

But this is already 1978, so there should follow your first engagements…

Finola Cronin:

That’s right. So what did I do first? I met somebody, as you do in London because it’s such a huge melting pot, who said… I didn’t have a job. I’d been in London for 2 years, must have been 1980. I thought what am I going to do? I need to get some money. Where were the jobs? The jobs were in Germany. But in order to get into the German system, you needed an introduction somehow. So I happened to meet somebody – I think I was always very lucky – who had been working in Mannheim, I forget her name. And she said I’ll introduce you to Biko von Lasky(?), because he was the agent in Frankfurt. So I met him and he said ‘Oh, I have a number of places you could go to,’ and he mentioned Coburg. I had never heard of Coburg. I didn’t know where it was. In the interim I discovered that Coburg is where Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort came from, from Saxe-Coburg. And this was this extraordinary baroque village that was surrounded, at that time on three sides by the DDR [GDR], so even to get to Coburg was an experience because you had to change trains three times from Frankfurt, because the gauge got narrower and narrower and there was no investment, because that was the end of the line. You couldn’t cross the border. I did an audition there, I thought it was absolutely terrible, that I didn’t want to go there and I came back to Biko von Lasky (?) and said ‘I’ve done that audition and they’d given me an engagement, but I really don’t want to go there; I’d rather go to Trier’ – which was the next possibility. And he said, ‘Oh, no. You’ll take that job in Coburg.’ So that was it. I wouldn’t get another chance. So I went to Coburg and as soon as I got there I resigned. You had to resign, because otherwise your contract would go on automatically.

So I got there, and then resigned, and then spent time thinking about where I would go next. And I did the audition tour, as people did in those days; they moved on. And as it happened I came to Wuppertal – so that was already in 1981. I auditioned for Pina. And the bizarre thing is that, in all the years I was here I completely forgot about that connection with Pina, and I never brought it up again. But actually what she had said to me that time was, she said, ‘You’re lovely but you’re very young. Come back to me later.’ So, that was an extraordinary idea, that 1981 Pina was still auditioning in the Ballettsaal; there was maybe 20 people there, you know? Five years later it was New York and there was maybe 120 people wanting to join the company. I do remember Anne Martin – we took class with the company. That was the audition and then we did a bit of work. So this was 1981.

What happened then, subsequently, was I went back to London, after that year in Coburg. I had got also a contract. I can’t remember the name of the place. It will come back to me later. Schindowski was the choreographer. I had the contract at home, and I wouldn’t sign it because I didn’t really want to go and work with him.

So I went back to London, and in the toilets in the Urdang Academy somebody introduced me to Vivienne Newport. Vivienne Newport was starting her company in Frankfurt and she had an audition. As soon as I did the audition with Vivienne… She asked us to do something really simple. She said ‘I want you just to walk across the room.’ She gave some sort of very simple warmup, and then she started to ask us to do things very simply: gestures, or walking, or so on. One particular moment she said ‘I want you to walk across the room and I want you to imagine such and such;’ I can’t remember what she said to us. Some part of me said, ‘I’ve come home. This makes so much sense to me,’ – to use your dance training, but to apply other ideas on top of that, somehow use that training to become, sort of, like a normal person. So it was kind of like, I suppose, a little bit the way actors work. It was like just imbuing lots of layers of different emotional characterisation, and so on and so on. I suddenly thought, ‘I really like this.’ And whatever she gave us to do, maybe some small gestural sequences, it seemed to be great fun.

So this was 1981 and she had met Peter Hahn, in Israel I think, on tour with Pina. Peter had said to her… She was just about to leave Pina. She’d been with her for seven years. She had come from the original group in Essen. Pina had asked her to come with her to Wuppertal. She had done all of this initial work, this extraordinary foundation of what would become the repertoire. And she really wanted just to go and do her own work. And Peter Hahn said, ‘well, you’re leaving. I can offer you a place in Theater am Turm, in Frankfurt.’ That theatre was just opening up – I think. I don't think it had been open since the whole Fassbinder scandal. It was just re-opening. It is a beautiful space, really nice space, not unlike the space we are sitting in in terms of the colour scheme; it was very black and white, black floors, white pillars and so on, lovely theatre size, lovely auditorium, lovely stage, really nice people there. She was, quasi in the freie Szene in Germany, but also she was lucky to be attached to a theatre. She had lots of independence, and Peter Hahn the Intendant was hugely supportive of her.

With her we made 11 pieces in about four years. In 1984, thereabouts, we were on tour, in the Kampnagel. We performed the Eric Satie piece that Vivienne had created for 3 dancers and a pianist where we sang songs, sort of a cabaret piece. Pina was there with Arien I think, in Kampnagel, that particular year. The big deal was that Pina and some of the company were going to see us in this piece. I remember Vivienne was very nervous. We were all terrified, actually, for whatever reason; Vivienne was completely nervous. And so in a way, I felt I was lucky again because Pina had seen me actually perform. And subsequently, maybe in November, December I came to Wuppertal and auditioned again. I heard nothing, and then suddenly I got a contract in the post, to come and to start with Pina, and that must have been maybe January, February 1985. And could I come immediately and start learning the repertoire. So that I did.

My first performance was in La Fenice in Venice, in 1985, probably June. The company had a very long tour there, of maybe six weeks. I was there for possibly two weeks or so. That was the beginning (laughs) – from the lead up into working with Pina.

Chapter 1.3

The legacy of Folkwang and Vivienne NewportRicardo Viviani:

Vivienne Newport was also in Essen, she probably had a lot of the methodologies of working, but that you just absorbed during the work. Now looking back do you see a difference in how they worked?

Finola Cronin:

My assessment of working with Vivienne: it was the first time that I had worked with this ‘task’, with Aufgaben, with so called improvisation, which they… That’s an interesting point to bring up, because Vivienne would set us a task. The first piece we worked we were five dancers: three women, two men. We worked for about two and a half months, and the piece was called Mist. It would have premiered in early 1982, I think. The way Vivienne’s process was working, clearly she was picking up ideas from Pina, in terms of asking questions. The difference I would suggest was that she allowed a lot of improvisation. The sense with Pina for me was that Pina asks for a task, but she expects that task to be formed, the shape of the task to be formed mentally and you take notes, before you perform the task in the process. This wasn't quite the same with Vivienne. With Vivienne I would say, you did your improvisation, and then came back and wrote what you did. So it isn’t a sort of composition in the same way.

The other thing as well was, clearly with Vivienne it was a smaller group and my sense was, when I came to Pina, that Pina edited. So you might get up and you might do a task, an Aufgabe, that lasted for five or six or ten minutes, and it would be very rare that Pina would allow you to do exactly that on stage. It would be chopped, edited, worked on, shaped, expanded or reduced, or whatever. With Vivienne that editing didn’t seem to take the same energy. Put it like that. That may have been because she had fewer people in the work. Or it might have been that she wanted more of a through-port, for some ideas more developmental of certain scenes and so on. I am not sure. I would nearly need to go back and look at her work now again, which I haven’t been able to do yet, to see exactly what it looks like. I only got a memory very much from the inside. With Pina’s work for example, many times we would sit out and watch what was happening, and also watch the repertoire. So in many ways one became familiar with a lot of Pina’s work, from looking as well as from being in it. Whereas with Vivienne it was always from the inside. So that would be one particular difference I would see with Vivienne’s work and Pina’s work.

Vivienne was also very conceptual. She was a very good reader. She was quite an intellect as a matter of fact, very well informed. She spoke excellent German. She was very well read in English and in German. She was approaching things much more intellectually. She didn’t work off – what I would suggest Pina did –, a lot off sensation and instinct. I think Vivienne was more deliberate, more conscious, more intellectual … more conceptually driven.

Chapter 2.1

The first seasonRicardo Viviani:

So in that first season there was Two Cigarettes in the dark, Gebirge, 1980, Arien, Kontakthof, Café Müller, Renate and Todsünden. Did you learn all of those pieces?

Finola Cronin:

(laughs) Apart from Two Cigarettes. I did learn all of that. I was asked to look at… certainly Sacre, which was torturous, because again I had never worked like this. I had never gotten my body into those positions, ever: lifting a shoulder, sitting in the hip, head back. It was just torturous, I think – I know – when I came – I think it might have been March in ’85, and I worked a lot with Beatrice Libonati, and would literally go from class, and after class I would work with Hans Pop, and then I would go home and lie in the bath for most of the afternoon and come back and work – solo work with Beatrice, two hours maybe doing the same movement, and go back and get into the bath and go to bed and get up and repeat the next day. My body was completely tortured. Absolutely tortured. It took me a long time to get used to those movements. They weren’t familiar at all. So of course for people coming from Folkwang that was their training. For me it was really very, very different. So it was a big deal. And at that time Jean Cébron was teaching, a little bit Hans Züllig. Dominique was still teaching a lot as well. So I had to learn the choruses for Sieben Todsünden, the Sacre. I was asked to look at Café Müller, because Nazareth was about to go. So I was looking at that. I was looking at Arien. Was Arien the following year? I was looking at Renate?

Renate – I performed Renate four times, only and I was jumping in for Nazareth. I do remember backstage, I had everything written down, because I still couldn't remember. It was such a complicated piece and I had so much to do. Great fun, but I really was running backstage to see what would happen next. Then I would run out and get the right costume, it was hilarious.

What else did I learn? Kontakthof of course, because then we were going on a big tour. In September 1985, we went to Canada, and then down to New York. For that we had to know Gebirge, and Kontakthof. Arien I wasn’t in. I was watching. Except I wasn’t there, because my father died, so I went back to Ireland, I didn’t see Arien at all. What else did we play? [1980] 1980 I wasn’t in but I was watching Anne Marie, which had actually originally been Vivienne Newport’s role. What else did we play?

[Gebirge] Yes, Gebirge was the chorus. So that was the beginning.

Chapter 2.2

How was the process of learning repertoire?Ricardo Viviani:

When we are talking about Jean Cébron and coming into this different trainings, did things somehow make sense, fall into place…

Finola Cronin:

Yes, gradually. For me it was a gradual process. It didn’t happen overnight. I personally found Jean Cébron to be a fascinating teacher, but I didn’t always understand what he was getting at. He was somebody that studied architecture perhaps, or was that Laban. I know Laban studied architecture. I think he was really into the space. That was quite fascinating. I really loved the classes of Hans Züllig. Later we became really good friends. On tour, we spent a lot of time in coffee shops and so on. I began at some point to really be able to embed those movements, because for me then I saw really a lot of what Hans Züllig was teaching was coming through Pina’s choreography. Very much so. So I felt I got stronger with that technique, that he espoused and taught.

Chapter 2.3

Learning a piece or createFinola Cronin:

There is a lot – and I am sure other people have contributed ideas to that – to be thought through with regard to the business of learning roles in Pina’s work. In so far as her direction, when her direction came, about your role, and the way in which you had to embody certain roles, one’s own confidence with that, how far to take certain ideas, and where to put limits on… Exactitudes: when did you need to be exactly doing what somebody had created previously and when did you have latitude? So there’s a huge amount of variance in the roles in which I learned, across all of those pieces of the repertoire that I learned.

But clearly, what I picked up from my colleagues in the Tanztheater at the time was: until you make a piece with Pina you really don’t know how she works. You won’t feel part of the company, until you make a piece with her. It was also a testing ground, you felt, for Pina’s relationship with you creatively and for your relationship with her creatively. So that was a kind of a rite of passage that needed to happen, that needed to take place. I had also heard from colleagues, ‘Pina is completely different in the creative process. She is extremely open to everything you do.’ That was my experience as well, that actually you could present anything in an Aufgabe to Pina. She would never reject it, ever. It may not end up in the performance. It might even continue to be part of ideas for her Reihenfolge [sequence] for the performance until the very last minute. And then it would be discarded, taken away. But her reception of your giving of your ideas, her reception was always open and generous and encouraging. That’s a fundamental way in which she worked, which was so appreciated, I would say by all of the dancers that therefore there was trust.

We watched other people’s work also with great respect. So the whole idea of respect, and communication around ideas… It’s very hard sometimes: you’re looking at work, Aufgaben from the other colleagues, and you’re really thinking, ‘What are they doing here? (laughs) I don’t get this, and how does what so-and-so is doing respond to Pina’s Aufgaben?’ And this was something that you might think privately, but you never would show that. And I am not saying that Pina thought that; I am saying quite the opposite. I am saying Pina’s whole demeanour was that she was receiving everything, in a very neutral way – but in a very encouraging, in a very positive way. The whole atmosphere in the Lichtburg, in the rehearsal room, during the creative process was really positive in terms of the emotional environment that was set up. I think she understood so very well, just so how difficult it is, and how challenging it was for everyone to stand up and to share some part of their personal history, which is what it usually was as well. Or the struggle that we had often, and I saw from some of my colleagues who’d been in the company for a long time – and I think that I found with myself the more that I worked with Pina – was that you really do, or did at times, feel that ‘I’ve actually got nothing more to say.’ You reach a point in the rehearsal after two months and there’s still a demand to create new ideas, and you feel completely dried up or have nothing left to say, or exhausted. I think Pina understood all of that, she really… You felt that she understood, as well, our own struggle. That’s what I felt – I shouldn’t say ‘we’ all the time –, that I felt she understood when it was becoming challenging. She tried to be sympathetic. That’s my assessment of it really.

Things then would begin to change a bit when she began to edit, when she began to throw things out. I think I said previously when we had the interview with Jan, Urs and myself and we discussed Viktor. I mean the biggest lesson I was told to adhere to from my colleagues was, ‘you make sure you know what it is you’re going to do before you do it, because you have to repeat it.’ For me the Aufgaben are composed, completely composed, and I sometimes get slightly irritated when I read people talking about the process, because I feel that’s something that’s not particularly understood in writing on Pina’s work – that I have read. That’s a very different kind of process.

Chapter 2.4

Pina’s QuestionsRicardo Viviani:

What actually don’t you find accurate when people describe the process of Pina’s Fragen [questions]?

Finola Cronin:

I’ll start with this idea, to what extent is the material for the work, even though it is shaped by Pina, to what extent is the… Where’s the Grundlage? Where is the actual foundation for these ideas? For me clearly – and I think Gabriela Klein has picked up on this – there’s an interest from Pina, that there is a sense of ‘this is the universe; it’s a microcosm of the world, there’s all sorts of different nationalities, and so on, that I’m interested in, different shapes of people.’ So clearly there is this connection through the Aufgaben und die Fragen, in terms of ‘what are you bringing to this material that will eventually be reduziert [reduced] or expanded, or whatever on the stage?’ But there must be this personal connection, from the Ursprung, from the very creation, a personal connection because you are asked directly, ‘what about the sun?’ for example. Or she would often ask ‘Christmas day’. Something like this. So she is interested in one’s experience of Christmas day. Now Pina, of course, is on record saying that the Aufgaben, and the information that is elicited from these questions, is actually not very important. She is on record saying that, as we know, where she says, actually, ‘Es bedeutet nicht so viel, die sind nur kleine Fragmente.’ [It doesn’t mean that much. They are just little fragments.] ‘I must bring everything together,’ she says. But clearly, it is not as simple as that. Even if she viewed it like that, I am not so sure I believe that is really what she thought, all the time. She might have thought that at some times. But that for me is the connection into different culture, into the so-called idea around a sort of a universalism, or inclusion, which is what I think is the human aspect of her work, is that it is linking through people of various nationalities, various different cultures, to sort of bringing this together to see, ‘where are the links, where are the divergences, and where is difference and where is similarities?’ And so on. I sometimes feel, in answer to your question, that because, in English at least, the term improvisation is that you start with the kern of an idea, and then you bring it somewhere else, and you allow your imagination to play with this. And of course in composition – I am stating the obvious here – you have thought this through, initially. Then you perform it – you enact it – but you know where the end point is. So that’s a very different process – in my view. And I think, that is not as clear for me, in some of the writing that I read. It seems to be glossed over. And particularly, if you think about somebody like Eugenio Barba, who has particularly worked with improvisation – in the world of theatre –, that idea of improvisation is something that is often lengthy, and developed and then people have a whole palette of material, let’s say Barba has a whole palette of material from his performance and then he edits subsequently out of one idea. You get that? I am being very pedantic now here with this. That is not the process that I experienced with Pina, at all. It was much more focused.

Chapter 3.1

Knowing the originsRicardo Viviani:

How important was learning one of those pieces that has very personal connections to a certain person? How important was it, at different stages, to go back to that person and ask, ‘Do you remember what the questions were there?’ Probably in one aspect or the other, in different pieces. What are your thoughts on that?

Finola Cronin:

For me that was really important, the Ursprung. It was important for me to know who had created this work. Because I was there – and I began really working in 1985 – there was still a lot of ensemble memory, if you like, corporate memory, from the original cast. I also came armed with a lot of Vivienne’s ideas of… She had spoken to me extensively about the work with Pina and about the personalities, so I came in with a lot of foreknowledge of – I am not saying it was authentic and true, but it was certainly some kind of knowledge – about the personalities and the colleagues, before I ever began to work with them. How important is it? I suppose it also depends on how you work as a dancer, as a performer and how you read the tapes for example, how you can look and learn. I mean, clearly when Pina is no longer with us that's a whole other discussion, because my experience as well is that Pina did split some of the roles, so they weren’t through-roles of the original cast, because she might say, ‘well you are very good at most of this, but there’s one or two scenes I’d like someone else to take over.’ So this happened. So the continuity of adhering to the original casts, roles, was already breaking down when I began in 1985. So already changes had been made, an example being the role of Vivienne Newport in 1980. Some of that was taken on by various people, depending on whether it suited the moment, or the scene, for example. Whereas the majority of her role might have been done by one person, it wasn’t carried through the whole production.

Chapter 4.1

Coaching and mouldingFinola Cronin:

I think also, my experience also was that sometimes I would have solo coaching sessions from Pina about certain roles, or certain scenes, for example in 1980. She would send everybody home and I would still have to stay here and rehearse a particular scene. (laughs) Rather scary, but I would have to do it. And that was my experience often that she would – not just me, but clearly for some of the major work, as in Sacre, for you know Opfer, and so on... We know that from the Probe DVD. You would have these one-on-one rehearsals with her where she would coach you. But my experience of working with [her], because I undertook Meryl’s role in 1980, and there’s a lot of speaking in that role. So Meryl had done it, then Silvia Kesselheim had done it, and I’d watch Silvia a lot. I don’t think I’ve ever got to see Meryl do it. Then I did that role for a very long time, actually. I nearly throughout… well maybe for at least five, six years while I was here, maybe longer. That’s what is extraordinary about Pina as well of course; all that speaking was in English, you know, and she had such an ear. We know she had a terrific eye for things, and watched very, very closely, but she also had a very terrific ear for pitch, for the tone of the voice, for pitch, for nuance, and so on. That was quite extraordinary. So clearly she wanted me to sound a little bit more like Meryl at times, and for me that would be very alien, because I am not Australian, and I think also Meryl was trying it on sometimes, pushing that sort of Australian… particular kind of Australian accent – I won’t say what I mean exactly by that, (humorous tone) but a particular kind of Australian accent. That would be something that wouldn’t have fit sometimes, in my view, with other moments in 1980 and some of the texts. There were some times I really felt she was trying to push me in one direction and I was really resisting that somehow. And she’d keep on and on and on. It was kind of extraordinary really. But it is also a testament to the way she did always revisit, revisit, revisit. So every cast change – I understood while I was still working here, and I think most of us do, who were working with her –, every cast change has a knock on effect on absolutely everything that is going on in the piece. And my sense was then, was that she would be readjusting: readjusting, getting the balance of the characters, the power play that happens onstage. That’s so important: ‘Where is the power? where is the audience‘s attention?’ And this was really what she was doing, during all the performances that she was present at, and our lengthy critique, you know? The critique went on for two, three hours, and she literally – looking back I would suggest – was organising the pace of the work, organising the pace. She would often say, you know… I remember her once saying to me, in the beginning of 1980 – In the first part of that lengthy work there is this scene where Meryl talks about… She has all the boxes, in Meryl’s role, and they drop down and she has the red coat on and she comes down to the front and she starts talking about, ‘I suppose you’re wondering where I got my earrings.’ So it’s a big sort of a Heiterkeit moment, slightly hysterical, and I remember once her coming to me and saying, ‘You did very well there, you brought the piece up. It had started very low; it started then you picked it up.’ I would say, I had no idea that I was picking the piece up. That wasn’t conscious on my part. But whatever happened, it was the right thing that she needed for the piece at that moment. And then that did make me realise that so many of the cues in her work are from people. They are not from music. It is like you enter the stage and the music comes up. Or you call for the music and it happens. So there are so many moments in her work that are really dependent on the performers inner pace. Which will depend on how you left the stage, how you entered the stage, what was going on before, and so on. Then you get an idea how delicate this whole thing is. It is like a cobweb, just hugely interconnected, and yet it is very fragile, and it is pliable. You can manipulate it, consciously or unconsciously. Looking back now I see her role was always to try and keep this coherence and cohesion around the work, to keep it particularly framed in a particular way.

Chapter 4.2

Helping the performerRicardo Viviani:

For a performer: you’re onstage, Pina is watching from outside – I’ll use my words – fine-tuning, or trying to get the pace. The importance to have these corrections being told, this process of corrections, as a performer to hear this feed-back of fine-tuning, does that help in your view for the performer to be more in tune with what’s going on onstage and picking up… you’re in the wings and you know you have to come into a certain temperature – now my words, ‘temperature’ –, is that what is happening?

Finola Cronin:

I think this is a fundamental issue in theatre, I would say, if I am looking at theatre in Ireland or in the UK, or whatever. It’s often a sense that you have the feeling that an actor has just joined the company when he comes on the stage; they’re not somehow in the same place, those who’re on the stage. This happens all the time in theatre, theatre that’s often brilliantly written but not well executed. I think that with Pina was that you carry everything with you when you come on stage. I don’t exactly, at the moment, have a memory of her saying that, but I think she did say that quite a lot: how you enter the stage is crucially important. And there were a whole load, a lot of backstage rituals also; people stood in the same place, or you sort of had a sense of where people were. But when you say, ‘did we know what was going on on stage?’ I mean, to be honest there were so many people, she had this ability to create extraordinary complex scenes, some of the scenes were even entitled ‘chaos’ (laughs) scenes, so there is a deliberate complexity involved in all of that, so I’m not sure I really knew – for example, in Viktor for the ‘Chaos Szene’ – what people were doing, until I saw a video of the work, because I was always in it. I knew what I was doing, but I was at the back doing something mad and crazy, and exactly what was going on elsewhere I couldn’t tell you. But then it’s about really embodying what it is you’re doing, and trying as much as possible to sort of do the same thing every time, you know, to be accurate. It is not always possible either, of course, because you’re always different.

I can still see her standing here in Schauspielhaus, going through the work, and saying, ‘and what comes next, and what comes next, oh yes, and when you did such-and-such, and you did such-and-such.’ And she would then maybe go off and talk to two or three people about a particular scene, about the timing, about – whatever: voice, where they are – really if you like, the staging, really the technical staging was, what I would say, were really the key issues around the critique. Not always, but mostly.

Of course if it was Sacre, or if it was Orpheus, or Iphigenia or something, it might require that we would go up and do an ensemble moment, dance an ensemble moment, because we were out of time with each other. That’s a different thing entirely. Because the music is there to set the frame and the tempo. The comings and goings, which she so magnificently choreographed, they’re very fragile. They are very open to being delayed, in which case it all drags, and sometimes we would feel that ourselves, I think, if things were too slow. We definitely would.

And there was a lot of watching. We did watch each other on stage. We did watch each other a lot. I have that memory of feeling very supported at times, that people are there watching. And maybe Dominique would say, ‘Oh, you know, what about such and such?’ and maybe have a word with Pina. I remember those kinds of little prompts from some of the more experienced, established colleagues as well, which were really helpful – because there’s so much, because these roles, and in fact all of the work in those pieces that I was probably most involved with, they are very complicated. They are complicated; they are very sensitive.

Chapter 5.1

Scenes in KlageRicardo Viviani:

If we talk about something like Klage, the film, what is the relation then? How was Klage – as a piece being formed by Pina in front of the camera with the material –, what was this experience like?

Finola Cronin:

It was long. It was very long. I suppose looking back I’d say that, in a way, it was exciting that liberation, not to be in Lichtburg, and not to be only onstage, but to be out in the nature, to go on site, to go on location; all that was exciting. There was a lot of hanging around. And then of course what I remember is that subsequently Pina had these hours of work that she then edited. So when we went to see it – I remember the opening night, which was up in Barmen, or maybe it was not in Barmen, I am not sure – there was a sense of really not knowing what was going to appear. We didn’t know what’d been chosen, and what had been discarded. That was rather odd. Then I suppose the one thing about the slow rehearsal process that is for the stage is that you get to know the material so well and you get to know the Reihenfolge so that even if, as Pina often did, change things quite late in the process or even after the premiere, there was still an anchor of lots of material that did hang together that made sense. For me personally I knew that I could deal with changes, it wasn’t a big deal. With the Klage I really couldn’t say that I remember the Reihenfolge. I couldn’t say that I really know the piece very well even now. I know lots of scenes. I’ve seen it many times of course. Very different.

Chapter 5.2

Scenes in a different contextRicardo Viviani:

Did the scenes that you filmed in Klage – we know what we have in the film – resonate with other pieces, with material from other pieces in her repertoire? Was there a correlation between scenes that were done for the camera and material from pieces?

Finola Cronin:

Some scenes are from other pieces, clearly, and I suppose one of the interesting things was that there was also material that was being made, that we had no idea it was being made, because we knew she might be working with two people but we didn’t know what was the outcome of that. And they’d say, ‘We did such-and-such,’ but you didn’t have a clue – that’s not quite answering your question. So, is there a correlation? Directly, I suppose a little bit, perhaps; the bunny, you know is a figure that appears in 1980. So there are those moments, but beyond that in terms of a thematic I think possibly, others might know this better, it excited her to have this possibility of being in nature, I would say, as well, about moving out. But I think it was a really big job at the same time.

Chapter 5.3

Transition periodRicardo Viviani:

Now looking into it, how do you see that period of the early nineties when we have the Madrid piece, Tanzabend II, Schiff, and Trauerspiel, which are pieces that were performed during a very short time?

Finola Cronin:

I suppose it’s a little tricky for me because I didn’t do Trauerspiel. And Wiesenland, was it?

Oh Schiff, yes. I didn’t do the Schiff, and I didn’t do Trauerspiel, so I didn’t do either of those pieces, but I was still in the company. I took… Stück mit dem Schiff kam zuerst, oder? [Stück mit dem Schiff (The piece with the ship) came first, right?]

So I stayed out of Schiff, because I felt I needed a break, and then for the next piece I had already put in my resignation, so there was no point in me staying. That was it. So I am not that familiar with those pieces, but I think with Tanzabend II, maybe the sense was… I am not sure that I was happy that she was happy with it. That was my own sense. It sort of needed something more perhaps, or… I am not sure. It didn’t seem to quite hang together. It was a very interesting piece in certain ways, but I’m not sure that it pulled together the way she might have wanted it to pull together. Maybe it is not correct for me to say that because I am sort of taking on board the fact that it hasn’t been played (laughs), very much, for whatever reason. So I don’t know.

What I feel from looking at her later work, and I haven’t seen all of the work, because I had quite a few years where I didn’t see her productions, but from some of the later work that I saw, obviously it was sort of a transition time, sort of moving away from that more theatrical scene, to a place where there is a different balance between movement and dance and the scenes, and the more theatrical pieces. It is definitely moving away from the idea of dance as gestures, representation of gender or as signification, moving into dance as movement, where some of the dance work becomes so complex and so dense that there’s a terrific sense of energy and a lot of emotional information and psychological information, and everything you need about character or about the way in which dance moves outwards into ideas of signification in its own way, with its own vocabulary and language. So this was really something that in some of those later works that she really achieves extraordinarily.

And, that has to be said, also because she had magnificent dancers to work, who really – whatever was happening with their training, and their background –, who really had that phenomenal energy to deliver that, to deliver those works and those pieces.

Chapter 5.4

Revisiting OperasRicardo Viviani:

At that time she brought back the operas: Iphigenia, Orpheus… Do you remember doing Iphigenia and how it was in that moment of time performing again – not performing for you, but for the work, having that being shown again?

Finola Cronin:

It was something very different. It was probably a little unexpected, I think, in so far as when we went back into that work I remember Jo Ann Endicott saying ,‘Oh I really like this work. It’s so gentle.’ But there was something about the sort of grace – Hans Züllig would say elegance –, there is something about the elegance of the movement which is quite astonishing beautiful, and poignant and glorious really, that she achieved. In fact I was not particularly looking forward to doing those operas, at all, but I absolutely loved doing them, particularly Iphigenia. It was just the most delicate of pieces, just beautiful: fine and quite magnificent really. So it was a thrill really to do them. And particularly because – I suppose it is an interesting thing – they weren’t balletic. Although I would say there were some ballet dancers with us at that time, but you realised that they weren’t balletic, so it was not that kind of elegance. It was still this sort of angularity that Bausch uses, and the hips would jot out and still very modern, but it was very soft. So it was quite a thrill to do that.

Chapter 6.1

Personal legacyRicardo Viviani:

How did the work with Pina inform your further [development]?

Finola Cronin:

Before I left I spent some time in London, possibly during one of the times that I hadn’t been working here, and I thought about maybe joining an acting company. And I had a look at the Theatre de Complicité, Simon McBurney, you may know, London-based, very interesting work. I remember I went to his company, the way that you could those days, maybe the early 90s and I said ‘I’d like to see some of your work.’ And he said, ‘Sure. Here, take some videos.’ (laughs) And I went back to where I was staying and I looked at the videos and I thought, ‘No, that’s not for me.’ (laughs) Because it was so text-based and this was a company… They are a terrific company, but they do a lot of work in physical theatre, but they work from text and they move out into physicality. So I thought, ‘No, no, actually I don’t want to work with another company.’ So by the time I was thinking about really leaving Pina, in ‘93, ‘94 – well I left in ‘94 –, I thought, ‘I really don’t want to go and work with someone else, why would I want to?’ There wasn’t really anybody any better – well we know that. In many ways, I’d say I used to think, ‘Well if Pina was working somewhere else…’ I think I got a little tired of Germany, more than... I certainly didn’t get tired of Pina, but I got a little tired of Germany, to be honest. I wanted a different kind of experience, and I did miss home. I was homesick. I wanted to go back to my own country. And that was one thing I discovered talking to colleagues. I remember one time in the Kneipe [pub] and it transpired, sitting around the table, there were maybe six of us, and we were all homesick, we admitted. So people who’d been away for a long time still had this sort of yearning at some level to connect to home, which is interesting.

I decided that if I was going to go back to Ireland, which I wanted to do I really needed a different way – I’d been gone for 17 years –, I needed a different way to connect and to meet people. Someone suggested that I go back to college and I thought, ‘Great, why not.’ Then once I started to study, at post-graduate level, Theaterwissenschaft [theatre studies], and I liked that also. I didn’t want to study dance. There is no opportunity to study dance in universities in Ireland – there wasn’t then – but I didn’t want to go to London to start, or to the University in the UK and start to learn about dance there as a theoretical subject. So I am still very grateful that I didn’t do that and that I went and studied theatre, because in fact there’s lots of correlations, and it is a kind of an interesting way to come into Pina’s work anyway, through theatre rather than dance.

Finola Cronin:

No, I continued to guest until 2001 – occasionally – with Pina. Since then, then I made some of my own work in Ireland in the early 2000s. // Which pieces? // I did a work-in-progress which I showed. Then I made a piece called The Murder Ballads with a lot of live music, again from Nick Cave and so on. That sort of murderous ideas. (laughs) Then I started to work with the Arts Council of Ireland, so in fact I couldn't apply for money because I was actually working for the body that donates money to the arts, so that put me in my place as sort of an administrator and specialist in dance. Then I started to work more in the University and did my Doktorarbeit [PhD], so really I kind of ran out of time. Later Raimund Hoghe asked me to do a piece with him in 2012, so I worked with him for a number of years. He made a piece called Cantatas, which we performed mainly in France, and also in Düsseldorf. I am currently working with an Irish choreographer, a woman called Liz Roche. We're making a piece connected with Goethe and W. B. Yeats, and so on, which goes on in September. So, I’m desperately trying to find my body. (laughs)

Chapter 6.3

Guest in WuppertalRicardo Viviani:

Which pieces did you guest here in the company? [Ismaël Dia:] How was it to come back as a guest?

Finola Cronin:

I came back for Viktor, and for 1980, and for Bandoneon.

How was it to come back as a guest? I came back the first time for Bandoneon; that was for the Argentinian tour. But I’d barely left. So it felt like I was still part of the company. Then I came back for Viktor and I was pregnant, so that was kind of fun, because I couldn’t do my whole role. It was really fun. All of my dresses had to be sort of changed. Then I came back for 1980, and it wasn’t the best for me. It wasn’t the best experience, because I came for rehearsals, probably in about June, then I came to perform. And I kind of felt a little ‘not quite here’. It was somewhere where I thought I needed more performances; we only had two performances and I thought… I think Pina might have said It would have been better if I’d had about four, to really get back in. So I didn’t feel I was quite on my game – put it like that – so it was a little challenging.

Chapter 7.1

Challenging creationRicardo Viviani:

But still in the chronology we have things like Palermo; Madrid we talked about.

Finola Cronin:

Palermo was probably not… I don’t know if anyone else of my colleagues would concur with me, but it was quite a challenging piece. We began it, then we left it, and went on tour and Pina was finishing with Klage, finishing the editing. So it was a rather protracted rehearsal process. My sense was that those breaks were challenging for it to come together. I personally was… maybe I wasn’t in a good place in my own head at the time, I don’t know, but I kind of didn’t have a lot of faith in the work and what I was doing, also a lot of my material had been cut out. So I was a little bit (makes sound suggesting she was miffed). And then of course there was this extraordinary moment with the Mauer, with the wall, and we had just been in East Germany, and been in Leipzig where all the Monday evening protests had taken place, so we were in the middle of history here in Germany, and the piece then had this extraordinary power and energy, of course. It is a magnificent piece, in so far as the energy and the way in which the Mauer as obstacle then is dealt with when it actually falls. So there is the practicality of that as a dancer, but then of course there is the symbolism of all of this, for the Zuschauer [audience]. It is an extraordinary work – and we felt that. We absolutely felt that. The sense of… the ecological message also, with the Müll [rubbish], with the dirt, with the dust, that sense of decay, of compostable rubbish and so on, and man’s behaviour in nature and so on, and the German thing and the wall. It just had… She pulled together such an extraordinary amount of end-of-century concerns for human kind. That is just phenomenal really. And I think that became clear, but I’m not sure that we were – I say we; I suppose me and close colleagues of mine –, we weren’t – I certainly wasn’t sure about it as it was being made, and didn’t feel particularly happy in it, but that didn’t deter from my view of it as just an extraordinary piece of work. Extraordinary.

Suggested

Legal notice

All contents of this website are protected by copyright. Any use without the prior written consent of the respective copyright holder is not permitted and may be subject to legal prosecution. Please use our contact form for usage requests.

If, despite extensive research, a copyright holder of the source material used here has not been identified and permission for publication has not been requested, please inform us in writing.