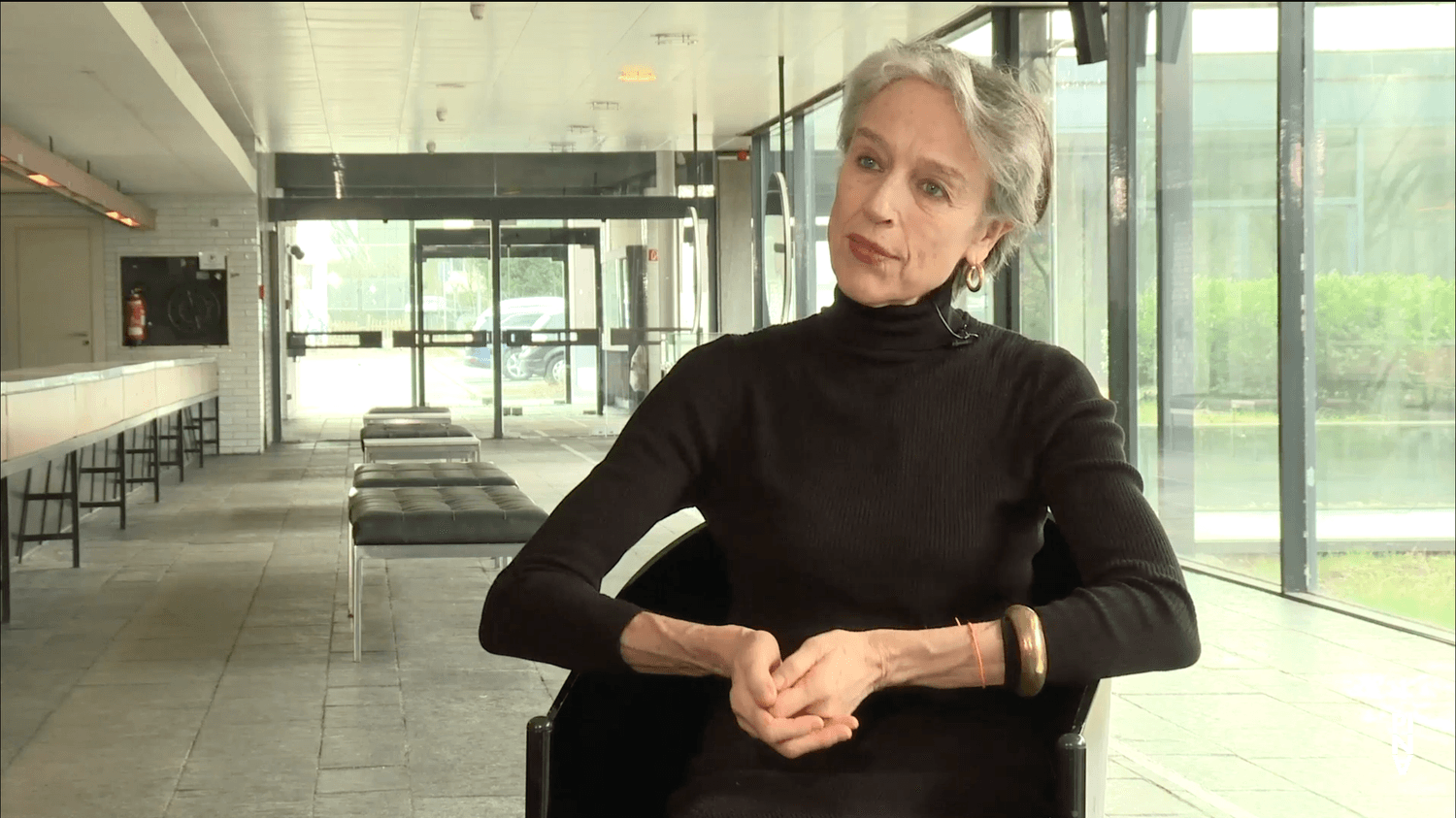

Interview with Jean Laurent Sasportes, 5/10/2018

‘My story might be quite an inspiration to young people who want to dance.’ This first statement of Jean Laurent Sasportes sets the pace of his biographical interview. In this Interview Jean Laurent Sasportes talks about his previous studies, finding dance only later in life. He gives an overview of his dance education in private dance schools. He describes meeting Pina Bausch and the process of becoming a member of the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch. He analyses and describes in detail the different nuances of the composition of the pieces. Focusing on Café Müller, he gives us an insight of how he approaches the part of Rolf Borzik. He also describes the artistic environment of Wuppertal in the 1980s in connection with the Free Jazz scene.

The interview was conducted in German and is available in English translation.

| Interviewee | Jean Laurent Sasportes |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Camera operator | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20181005_83_0001

Table of contents

Chapter 1.1

Finding danceRicardo Viviani:

Tell us about your dance career and how it led you to Pina.

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

I reckon my story might be quite an inspiration to young people who want to dance. I was at university and I’d been doing maths, physics and chemistry for two years. Then I thought, although I found maths and physics very interesting, I probably didn’t have the necessary depth of knowledge, and I needed concrete examples to really understand it. And these were the early days of the environmental movement, so I decided I’d like to be an oceanographer, to research the sea. I really admired Jacques Cousteau and all that work. Then I thought, if I want to be an oceanographer and ecologist, the best route is through natural sciences. That led me to study pharmacy – not to be a pharmacist, but because the modules in biochemistry and other subjects were much more intensive on that course. After that you only had to do a year of specialisation, then you were done. But after two years of pharmacy at university, I realised I couldn’t carry on. As always, the subject you’re studying is interesting, but the environment wasn’t really right for me. Then I decided to enrol at a polytechnic in Canada. I did all the paperwork, everything was ready for me to start at the polytechnic. Luckily I had excellent references from my former maths and physics teachers – not because I was all that good, but because they were so nice. A month before I had organised to travel, I met up with a friend in Montpelier who was in a small amateur dance company – Anne-Marie Porras, a modern dance teacher who still runs an important centre in Montpelier, Epsedanse. She was there with her dancers and she introduced me. She said, ‘you have to come and see what we’re doing. We rehearse tomorrow.’ The next day I went along to watch. My first encounter with dance – although I did like to dance a lot, to be moving. So I watched them rehearse for the first day, and the next day’s rehearsal, and so on for the whole week. I was a student; I had lots of time and could do what I wanted. After a week when I was there every day, the dancers said to me, ‘stand there and copy us.’ They were very simple movements really. I can still remember them. So I had a go and it was fun, and then they said, ‘We’re going on tour’, a short tour; it wasn’t a professional company. It was summer. ‘We’re performing in a few small towns. Do you want to come? You can join in on the choreography you’ve learned, carry on doing the training beforehand, help us with the sound and light.’ So I went along, and then I started thinking, what am I going to do next? I like this so much, what am I going to do? It really was a tough summer in the sense that I had to make a decision; in September I was going to have to decide whether I was really going to the polytechnic in Montreal, which my father was pretty pleased about, or, well… I wasn’t sure what. I wanted to dance. I had a few sleepless nights, I talked it over with a few people, and I decided to try and become a dancer. Then I told my father. I must say I admire my father. He was like any father, wanting what’s best for his child. But ‘what’s best’ does not mean having money problems; it means having security, respect from society, which I fully understand now I have a son. At the time I was 22 or 23, and I’d got quite far with my studies. I still had a few years till I was finished, but still. And then to say I was jacking it in to start dancing… At first he was very shocked, then my mother worked on him for ages – she was great. She thought, of course I want what’s best for my son, but what’s best is what my son likes to do. She was a great help, and then my father said something really amazing: ‘Look here, I’ll carry on giving you money for another year, as if you were still a student. After that year you’ll get half, and the year after half again, and after that you’ll have to manage on your own with your dancing, ok?’ So then I knew that if I got into trouble, he wouldn’t let me starve. So that’s how I started.

Chapter 1.2

Bejárt and LimónJean Laurent Sasportes:

Then I started training with that company – as much as possible, obviously. And then we met Jörg Lanner, a major contemporary dancer. Jörg Lanner had been one of the main dancers in the Maurice Bejárt company, there from the beginning. At the time he was still married to Lise Pinet, and the two of them were the famous Romeo and Juliet duo in Maurice’s choreography. They had just moved to Montpelier. They weren’t part of the company any more; they had opened up a dance school. Of course we went straight there, and it was there I did my first ballet classes and started to learn modern dance. I stayed with that company for two years, and started writing pieces too, synopses of pieces, till I decided to try my luck in the professional world and move to Paris and challenge myself on another level. I started giving dance lessons to beginners very early on. It was a good opportunity to recap what I had learned myself. And I could also earn a bit of money. And why Paris? We had started inviting other companies down to Montpelier, including Peter Goss’s company, and we became very good friends with them. I had my sights set on Peter Goss, not to become a dancer in his company, just because he was an amazing teacher – is an amazing teacher. I really wanted to take lessons from him, so I started at the Centre de la Danse, in Bertin Poirée, Paris. There you just paid for your classes, not like at the conservatoire, or the Folkwang School, where you audition for a place. It’s the same in New York; you have to pay for classes, then at some point you do auditions and if you’re lucky you will get into the industry. So I did all sorts of classes with Peter, three or four training sessions, as well as ballet. I started working in the school canteen so I didn’t have to pay for my classes. Later in the summer I started to stand in for the dance teachers when they were taking a break.

Chapter 2.1

Visiting WuppertalJean Laurent Sasportes:

Petit à petit, I managed to improve, and at some point I started doing auditions. One of the auditions took me to Munich. There was a choreographer called Birgitta Trommler, and I stayed there six months. At some point someone told me Pina was looking for men for her company. I didn’t know who Pina was, but this person, who knew me very well, said I would really fit in. A bit later I travelled all the way to Wuppertal, without knowing anything else. I stayed with this person, in Essen, and went from there to Wuppertal, to the Opera House. I didn’t know what Pina looked like. I asked the porter, ‘Where can I find Pina Bausch?’ ‘Go to the canteen. She’s probably there.’ I went in, asked at the counter where Pina was, and they gave me a strange look and said, ‘At that table there.’ There were four women sitting there: Pina, Marion Cito, Vivienne Newport, and Jo Ann Endicott. I didn’t know any of them. At the time I had hair down to here (points to shoulder) and boots up above my knees. I approached Marion Cito first, and said, ‘are you Pina Bausch?’ The other three laughed, then all four, very loudly. Pina looked at me and said, ‘I’m Pina.’ She just looked at me (laughs). I said, ‘I’ve heard you’re looking for men.’ They all laughed again. ‘Yeah, yeah, we’re looking for men.’ I introduced myself. She was very amused. ‘We have a dress rehearsal today, come and watch. Tomorrow I’m doing training with the company, after that maybe I can have a look at what you can do.’

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

It was the dress rehearsal for Arien. So I watched it. I had no idea what kind of work Pina did. And while I was watching it, I noted down somewhere, that I’d seen that Pina was howling, howling all the things I wanted to howl. It was exactly what I… this world… The next day I joined the company for training. They were all there, Dominique, Malou, such experienced people. There I came with my long hair and four years of dance at the most. They all tried to suppress their giggles. But I was on a cloud anyway. I didn’t notice much. Then I did the training, and afterwards Pina asked me to do a few things, a short audition. After that she said, ‘I’m going to Paris with the company’ – she was just about to do her first guest shows at the Theatre de la Ville, with Bluebeard I think – ‘and I’m going to hold auditions there. If I don’t find anyone there, let’s talk in three weeks’ time. When I’m back, we’ll see.’ I went back to Munich, and three weeks later I got in touch. Pina said, ‘No, I didn’t find anyone, so I’d like to meet you again and see what you can do.’ And I said, ‘I’m not sure where I can stay. I don’t know anyone in Wuppertal.’ She said to me, ‘Ok, then come and stay with us.’ (laughs)

Then I arrived and Pina introduced me to Rolf Borzik. They lived in Fingscheid, and I was given the guest room. I’m not sure why, but I was so overexcited I got toothache – ghastly. I couldn’t do a thing. I stayed in the room for two days, and Pina and Rolf brought me tea. (laughs) When I emerged again, it was the end of the season. This meant Pina had some spare time, which was very rare, and we went to the Opera House. ‘Have a warm-up; I’ve got a few things to do at my desk, then we can see what you can show me.’ I warmed up, then she asked me to do some things. Later I realised what she was asking me to do were things from the repertoire, all kinds of things. After three days of this – I’d been there nearly a week – my nerves were completely shot. But we were having a lot of fun together. In the evenings we went to restaurants, and it was all very relaxed. After that we went to Cologne - after three days. There was a big dance festival there. Pina had been invited, and while I was sitting alongside Pina I met Alvin McDuffie, a modern dance teacher I knew previously. Pina knew him too, of course. Alvin turned in my direction greeting Pina, then saw me and said, ‘Oh Jean, what are you doing here?’ ‘I’ve come for an audition with Pina.’ Pina was the other side of me, and I added, totally naïvely, ‘but do give me your address in New York; I’m not sure it will work out.’ (laughs) Totally naïve. He gave me his address and we went back home. Then I said, ‘Ok Pina, it’s been great fun with you and Rolf. I like being friends with you. If you really don’t want to take me on, tell me, I’d understand. They’re two separate things.’ She said nothing. We had met two young dancers that night in Cologne who asked Pina if they could audition. Pina told them to come by next day. Then it wasn’t just me auditioning, the two boys were there too. And Pina said, ‘Jean, you know the movements from the start of Sacre, we’ve done it often enough. Please teach it to them.’ To be honest, by that point I was thinking, fine, I’m out of the picture now; she wants to watch those two and doesn’t want to see me perform at all any more. When we were finished, we met the boys in the canteen, they came up to Pina and she said, ‘I’m sorry, but I don’t think it’s going to work.’ They left, disappointed, of course. She looked at me and said, ‘You see, I can say no if I want to.’ (laughs) Then we went back home, she lit a cigarette, looked at me, and said, ‘Yep, I think we’ll give it a go.’ (laughs)

The day after I went back to Munich. At the station I felt like… Do you know the film Next Stop Greenwich Village? There’s an actor who gets a role, and he’s on the platform at the station and starts dancing on his own and the policeman in his helmet gives him a strange look. That’s how happy I was. And that’s how the whole thing began.

Chapter 3.1

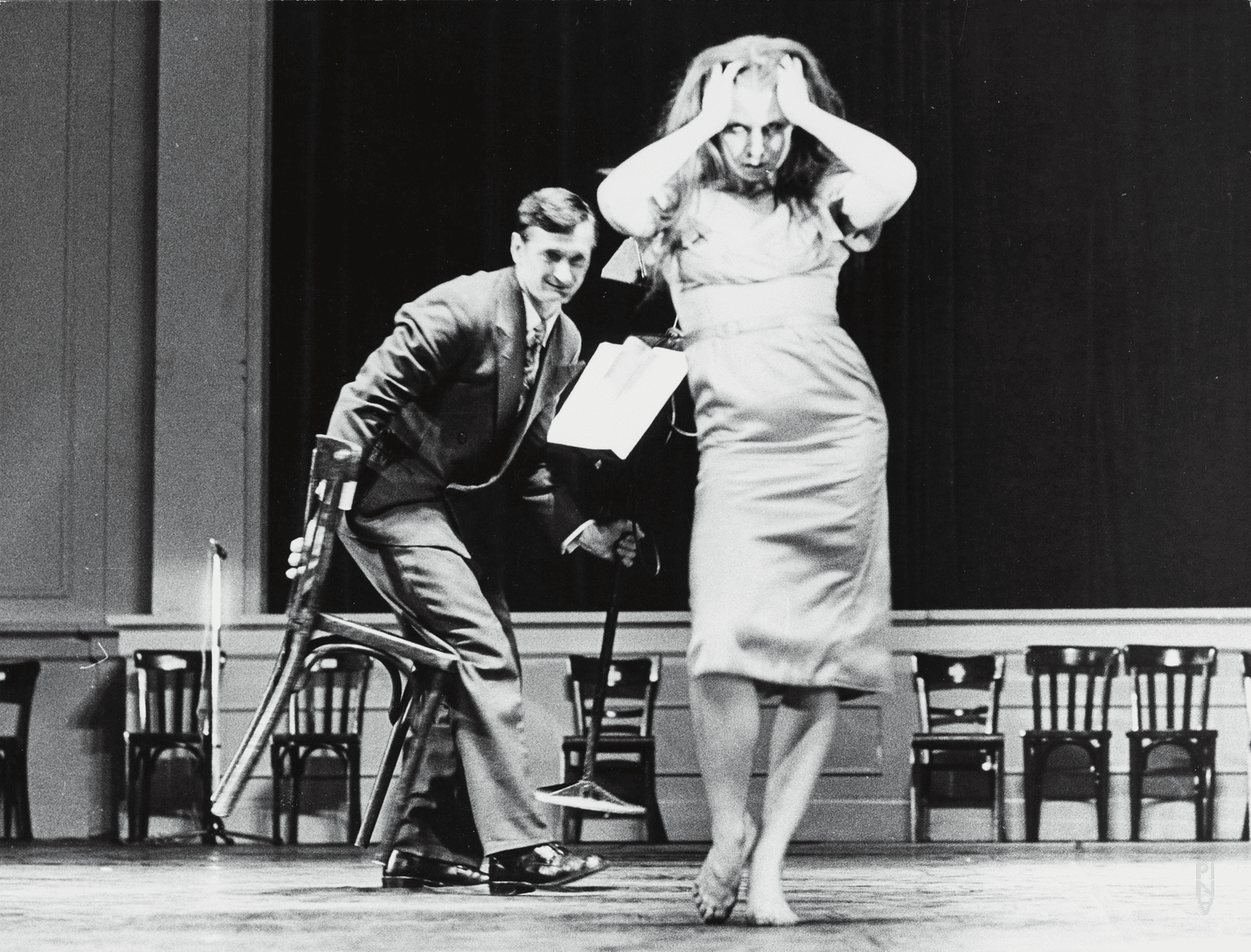

Performing Rolf Borzik’s roleJean Laurent Sasportes:

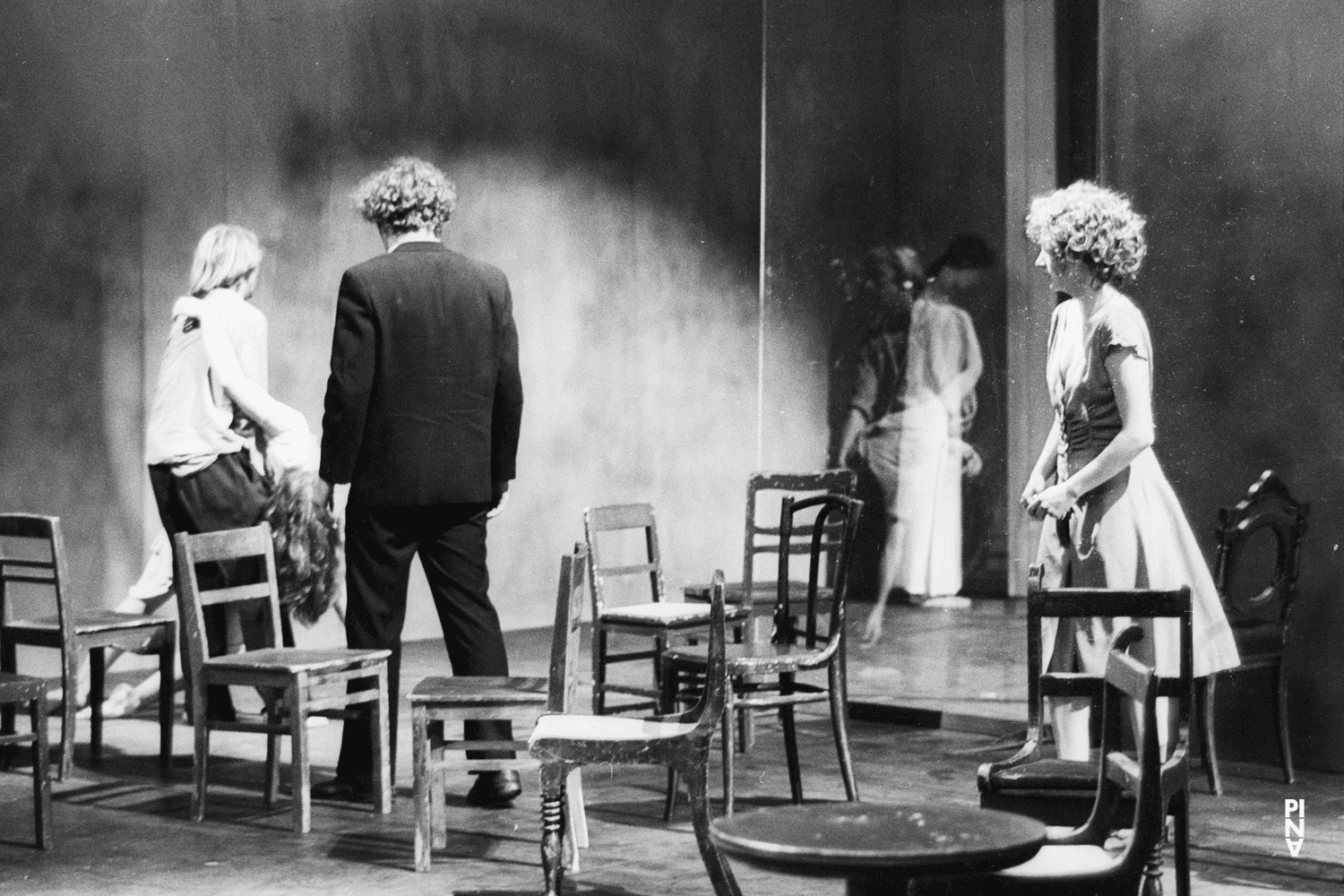

The first piece I had to get to grips with was Café Müller. Because – I’m not sure when exactly – we had to perform it in Nancy, and Rolf couldn’t perform any more. I had to learn it. I think that was my first show.

Chapter 3.2

Learning Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

Could you perhaps explain for us, how you learned the role, if you can remember it. At that time Café Müller had only been performed five times. Did you use video, or help from other people, Malou and Dominique? Were the tracks already determined, was it firmed up, how was it?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

At that time teaching was done using video, poor quality, black and white video, but you could still see. And of course Malou, Dominique, Pina and Jan really worked with me, especially Malou and Dominique. The tracks Malou and Dominique had taken in the choreography were pretty precise, but not so precise that everything was under control, not at all. Particularly then, because there were an awful lot of chairs, more than there were later. Malou and Dominique wanted it to stay as natural as possible, quite rightly. They are highly professional, when they help someone. Obviously they want to bring this person up to their level. I remember my first performance, in Nancy, was in an old café or something like that.

Chapter 3.3

Ancien Garage NancyRicardo Viviani:

It was in an old car salesroom, used during the festival, to the north of Nancy, almost on the edge of the city.

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

Exactly, and the audience were outside on the forecourt, looking in through the plate-glass windows.

Chapter 3.4

Restaging for NancyRicardo Viviani:

I’ve seen in photos, in documents, that this garage has windows on three sides. The audience watched through the windows. You can see it in the photos. But perhaps you can tell me how it felt to enter this space.

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

That’s what I remember – with the audience divided from us by the plate glass, and millions of chairs (laughs). Later I worked out there were 120 chairs, and an incredibly number of tables. And if you have no experiences of this piece, in this role you seriously think you have to be everywhere at once, you have to make space on all sides – which of course isn’t possible. So in the beginning, at first, you are in a panic, and you move lots more than you generally should. It’s not actually about seeing Jean moving the chairs around; it’s about Malou, Dominique, Pina – their dancing, their feelings. I just have to make sure they don’t injure themselves, and otherwise try to stay inconspicuous. Of course I did the opposite, but I think that’s what anyone would do. It was a nightmare when you moved the chairs out of the way too quickly, and then you had too many chairs, they piled up, and you had mountains of chairs. The dancers were perturbed at first, because they had to take detours. That was my first experience.

Chapter 3.5

ChairsRicardo Viviani:

The chairs were very different then; you can see it in the photos. Did they break?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

The chairs were all different from each other, perfectly normal chairs. Obviously they broke more quickly than the prepared chairs used later. ‘Prepared’ just means that they had metal brackets screwed into them, that’s all. And the tables weren’t like the ones later. One good thing is that the tables were round on top, but not below. They didn’t roll away, like the next generation of tables, which is very good, because when you’re busy and you’ve got two or three tables rolling across the stage, it doesn’t make it any easier. Of course my second big experience of Café Müller… – because in Nancy it was only a couple of times, I think…

Chapter 3.6

From Nancy to touringRicardo Viviani:

Yes, a couple of performances, very late in the evening, and just Café Müller. It led straight to the next experience.

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

And the next experience was a big tour of South America. It was my first tour. There I had that role in Café Müller, and I was also a dancer in Sacre. Malou and Dominique too, they both danced in Café Müller as well as Sacre.

Chapter 3.7

Kontakthof – The most beautiful thingRicardo Viviani:

Kontakthof. Did you perform in Kontakthof?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

Yes, I did Kontakthof too. There were a lot of performances of that. The great advantage of that is that you can slowly build up experience, then build on that experience to improve, try not to be so conspicuous, but more efficient, with more feeling. Dominique and Malou were never satisfied, never. It sometimes went so far I started crying. We were actually talking about it yesterday; we went for a meal together. Malou said to Dominique, ‘Do you remember, we were brutal, we left him a wreck.’ (laughs) Obviously it wasn’t malicious, just because they demanded so much of you. The role really is wonderful. It’s the most beautiful thing I’ve had to do in this job. You aren’t concerned about the audience, or about presenting yourself, almost the opposite; you’re a person on the stage. You shouldn’t be a presence, but you have to be there throughout. That means you touch on things you engage with at a much deeper level than if you were presenting yourself to the audience. Nothing against that, I love to do that too, but I noticed that I learned a lot through Café Müller. We did an awful lot of shows in total; it was a huge tour. After that I was gradually able to work more intensively on the sensibility.

Chapter 3.8

Borzik’s fingerprintsRicardo Viviani:

Rolf Borzik created this role originally. Were you aware of this the whole time?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

He never got involved in the rehearsals really. I think he gave me some tips a few times, but Malou and Dominique, and Pina too, said 5000 times, ‘No, Rolf does it like this.’ I respected that, but the problem was I got the feeling I would never manage it. Later, when I knew Rolf better – partly through stories people told – I realised the role had to have been created by someone like Rolf and was best performed by him. At some point perhaps I may have got it right: someone genuinely presenting themselves as a person. If you’d said to him, ‘Rolf you’re going to be on stage with audience looking at you,’ he’d have said, ‘No, then I’m not doing it.’ And I think that the role really began with that attitude. That’s why it has a particularly good quality, very human...

Chapter 3.9

Special spacesRicardo Viviani:

Back to Nancy, and a few other locations which impose particular conditions on a piece like Café Müller, where you have to exit the stage on one side and come back on from the other – that wasn’t possible there. How did you get round it?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

Initially I wasn’t really aware of it, because I didn’t know what it was like on a normal stage. But if I remember the original video correctly, Rolf was often in one corner, a dark corner. He didn’t necessarily exit. He was a bit more present, I think. Actually that fits the scenario better – that this person is in fact in the room, in other words, making sure the customers, or people, in the café don’t hurt themselves. It makes sense for him to be in the room. That’s why I think for me that felt pretty natural. I just had to be in a corner, discreetly present, without really being there.

Chapter 4.1

Keuschheitslegende – Pina’s work processRicardo Viviani:

Perhaps we could go forward in time a bit. The next thing which happened was the creation of Keuschheitlegende. What was it like as a process? Was that a new experience for you too?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

Yes, of course. On the one hand I didn’t have much experience of professional companies, but what I was interested in was creativity. And then there was this process, where you get questions, and you search through your memories, your imagination, to find material to answer Pina’s questions. It suited me down to the ground. Later it was like being in a kindergarten and being able to do absolutely anything. The imagination knows no bounds. Pina’s questions weren’t things you necessarily understood and answered terribly directly. Quite the opposite. Sometimes the misunderstandings of the questions were even more interesting than if you tried to pander too much to what you thought she wanted to hear. That’s why it was so wonderful. In Keuschheitslegende I had enormous fun. In fact I must say I had enormous fun doing all the pieces which followed.

Chapter 4.2

1980 – doubt and reassuranceJean Laurent Sasportes:

1980 was the second piece I did using this process, and I know I had a little moment of doubt. I mean, we did this process, provided material, and at some point Pina was busy with the material trying to make a piece out of it. I know I did question that. I thought, is it like putting a load of stones in a bag then at some point pulling a few of them out and building a piece. I can remember the dress rehearsal for 1980. I think I was considering the difficulties Pina had. She was very affected by it emotionally. She told us a lot about what had gone on, to explain how it related to the questions. She didn't tell to explain it to us, she just told it to tell what happened. Then you could understand why this or that question was asked. And perhaps because she was trying to build the piece at the time, I began to wonder, and query it. I still remember that at the dress rehearsal I suddenly realised what kind of a genius was behind this. I can’t explain it, but while I was in the midst of this run-through, suddenly I didn’t challenge anything any more. I sensed the genius behind it, that it had been a procedure, not taking stones from a bag and sticking one after another. And then I never doubted anything again. Quite the opposite. I work in this processual way to this day, or remain very influenced by it. I think it’s a very intelligent way to work with other people’s creativity.

Chapter 4.3

Schauspielhaus WuppertalRicardo Viviani:

We are talking about this space. 1980 was premiered here [in the Schauspielhaus]. I think so. People talk about Pina seeing more, looking more closely. Two questions: firstly, when you said that at the dress rehearsal you saw that it all made sense, was that also a learning process in your work with Pina? To put it more precisely, what do you get when you ask questions, and get this input? What does it bring?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

I was in the dress rehearsal, yes. That sense came to me when I was on stage. I can’t pin down the moment. It was more like a feeling, something you feel, like when you are listening to a piece of music and sense the beautiful harmonies of the composition without analysing it, without explaining why you have this feeling. It was a very subconscious doubt anyway; it just slipped (gestures a fine line) from admiration to slight doubt, and then what I felt there on stage, what I understood, about why this scene comes after this scene…

Chapter 4.4

Open your heartJean Laurent Sasportes:

Thinking about it now, when I felt that, it was beyond admiration, more a huge sense of trust – in Pina, in what moved her, and what she wanted from us. It became clearer to me, without me needing to spell it out. Perhaps what I learned through this trust is a bit like what I later learned through improvisation, in that you learn to trust something which cannot be explained, something which is about nature, something organic, something you have within you. Basically you open the door to your heart; you learn to open the door to your heart. And that is what I learned in a big way with Pina. In as far as you can learn that. It’s a journey. You can never say you’ve finished learning; you’re always learning.

Chapter 4.5

Special peopleJean Laurent Sasportes:

There’ve been many people who’ve changed my life and three of them are particularly special: one is Pina, another is Kazuo Ohno – we met him in person too, and saw a lot of his work, in Japan too – and the third is Masamichi Noro, the founder of Kinomichi; I worked with him for 25 years. Kinomichi is something I still teach. These three masters – they knew each other too – had one thing in common; they all had hearts with great big open doors, and what they teach you is that that’s a good path to take.

Chapter 4.6

Compositions, not improvisationsRicardo Viviani:

Pina asked questions, you improvised, and then she’d say, ‘No, we’re not improvising.’ Can you tell us something about the working processes?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

At some point it was claimed that we improvise. That’s not the case at all. It was never the case. Pina asked us questions. These questions didn’t come from nowhere, of course; they were closely related to what she wanted to say with the piece. That was never really explained to us. We didn’t have a talk or anything at the start to find out what the piece was about. I think Pina had a massive distrust of anything too cerebral, too intellectual. Quite rightly – it can be disruptive and dangerous. The intellect can have too much power, and destroy creativity and sensitivity. She asked questions which were sometimes very personal to her, as in 1980. The piece 1980 was about Rolf and his death. It was a lot about Rolf and her experience with him. That’s not something which can be understood from the piece – that’s not what it is about – but it is about the emotions she was having then, emotions which any human being could feel, each in their own way. To the average audience member the piece isn’t saying anything about Rolf, but it describes particular emotions which are very human, very deep. It was a personal piece. There are pieces that are less personal. Palermo Palermo is very much about the city of Palermo, although obviously seen from a very interpersonal, sensitive viewpoint.

Chapter 4.7

Examples of Pina’s questionsJean Laurent Sasportes:

So you’d get a question, for instance, like, ‘What were you afraid of when you were a child?’ That’s a question where you can draw on your own experience and memories, and effectively tell a story, through movements, anecdotes, or scenes, about what you were frightened of as a child. Everyone has been afraid as a child. When that comes in a piece, although it’s not connected to a story intellectually, it still speaks to certain sides of a person’s sensibility. Then you’d have to consider whether to use memory or imagination; there are some questions which can only be answered with imagination. Then throughout the short scene you might play a character which wasn’t necessarily yourself; you performed something else. The possibilities were incredibly wide. I often said to Pina, ‘Sorry, I’m going to do something very stupid, but I want to get it out of my system.’ She understood, of course. Who knows, sometimes she might actually use it later in another context.

Chapter 5.1

Compositions can be repeatedJean Laurent Sasportes:

You gave it some thought, practiced, rehearsed, and then when you showed your response to Pina you were very clear what you were doing. That’s not improvisation; I call it composition. If you had been improvising, you needed to be very, very good, because Pina would ask us a month later, ‘You remember that thing you did three weeks ago? Can you please do it again exactly the same?’ And if anyone who improvised something three months ago can perform it again precisely… Well I wouldn’t manage that. It was not about improvising.

Chapter 5.2

ImprovisationRicardo Viviani:

Later you did work with improvisation. How was that? Could you describe it?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

That’s something else again, yes. It’s worth saying first of all that in the 1960s, Wuppertal was the European centre for free jazz. To be more precise, here the musicians who had become famous in the free jazz field developed an important movement for musical improvisation further; later it liberated itself from free jazz, because in the 1960s free jazz had been more of a reaction – it became free improvisation. Then I met Peter Kowald. Peter became a very good friend and I gained my first dance-improvisation experiences with him. I think it was in 1994 I did my first performance with him and some other musicians. Then I got to know more and more musicians and did more and more improvisation performances. I also created a piece that was more like structured improvisation, Short Pieces. And I still do it. That really was something very different from the work with Pina, even as a choreographer.

Chapter 5.3

Still needs researchJean Laurent Sasportes:

I’m coming at this late in life, but an angle I’d like to research is developing a dance theatre piece using structured improvisation. I think a kind of improvisation somewhere between non-improvised choreography, where everything is determined, what, when, where and how, and complete improvisation, where everything is open, could open up an awful lot of possibilities. And what I call structured improvisation is really that you determine certain things, agree which material you are using, or when, etc., and leave the other options open. That’s something I’d love to have investigated – to have the quality of a pre-scripted dance theatre piece but also the spontaneity and liveliness of improvisation as well.

Chapter 5.4

Freedom of the performer in Pina’s piecesRicardo Viviani:

What’s the relationship between structure and freedom, or decisions the performer is responsible for in the moment, in Pina’s work?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

Essentially it’s all predetermined. Pina didn’t like it at all when you allowed yourself to do something different from what was really planned, because it was all scripted – but I always felt very free as a performer, as a dancer in my work on stage. Somehow you have a lot of freedom within these restrictions. The timing is fixed: when you do what. You have particular cues, very precise. That’s understandable, because it’s very complex. You get the impression we’re improvising on the stage, because it’s very complex. It’s a polyphony, which can only really maintain its quality from one event to another when this polyphony is very precisely composed, because otherwise you’d have nights which went very well and others which were catastrophes. If that polyphony disintegrates it becomes free jazz. But I still wonder where this sense of freedom came from. I still don’t know.

Chapter 5.5

Example Arien – Paths of the sequencesRicardo Viviani:

A piece like Arien, for instance. It portrays a very free situation, where these people… like Sacre, where the music plays and there are all these people on the stage; everything has to work, otherwise they collide…

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

In Arien too. It’s all very precise, just like in Sacre, in other words this happens at a precise moment. In Sacre it’s the music. The music is the timeline: when this note comes, or after so many beats, you change from this movement to this movement. It’s very fixed, and very ordered. From the auditorium you see a group of dancers doing the same movement in unison, or sometimes doing solos, and I think it’s just that the composition is very ordered. The composition of Arien is not quite as ordered, in the sense of whether I put my hands here, or here (makes alternative gestures); there are certain scenes in Arien where it doesn’t matter, as long as it happens. All the same, what happens, when, and where is dictated precisely, but it’s not based on the music, more on the sequence of scenes: not one scene after another, but, for instance, I know I have to come on, run around, talk on my own as if in a trance. I only do that when he (points) sits down. How long I do that for, is not dictated so precisely. I really do have to do it till I’m exhausted. But I still can’t run around there for half an hour.

Chapter 6.1

The group in KontakthofRicardo Viviani:

There are pieces where the whole co-operative, collective thing is very strong, particularly in relation to the complexity of interdependence, of the energy on stage, in Kontakthof, for instance.

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

I was just thinking, Kontakthof is really a dance theatre piece, compared to Sacre, which you could say was more of a danced piece – but the composition is just as clear as in Sacre: the groups, sometimes a little solo… But in terms of the structure it remains really just as ordered, or you might say, that this order is easier to see, to feel. In pieces like Arien – that’s a very good example, because it’s extreme – there really is a sense of chaos, but it isn’t chaos. The composition is concrete and fixed, and learnt; it’s just that the feeling it generates is one of panic and chaos. This is deliberate, of course, because that’s what the piece is trying to say.

Chapter 6.2

Achieving truthJean Laurent Sasportes:

The stylistic difference, in other words, there are pieces which are firmly structured, one extreme is Sacre, and some are highly structured, such as Kontatkhof. To me, Kontakthof is a very firmly structured piece, in the sense that even when we weren’t quite at our best, the piece remained strong. A piece like Arien is very sensitive, because if we’re not as profoundly involved, the evening isn’t as profound. I think that’s because that style is more sensitive. What it lacks in terms of a clear structure, it demands in the authenticity of what we are expressing there. That does not mean that in Kontakthof or Sacre that nothing comes from within, but the structure of the piece helps hold the piece together better. In Arien, if too many people aren’t really invested or authentic, the piece falls apart.

Chapter 7.1

PrioritiesRicardo Viviani:

The question is, when we’re thinking about teaching the pieces, how do you achieve that quality? Is it about form or representation, which may or may not be the same thing? Altogether, for the person teaching it… Let me try to formulate a question: To teach the pieces, do you have to identify the priorities?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

That’s a very delicate question, of course, how you can teach this. I experienced it myself initially. There were several pieces I learnt, which I hadn’t been part of from the start: Kontakthof, Arien, all pieces created before my time. But I was very lucky; Pina was there and the people from the creative phase where there, always around. That meant I always had first-hand information on the role. I think that’s very important. As you say, there is this formal side. You watch the video to see what you have to do – I’m talking more about a dance-theatre piece. A danced piece like Sacre is easier in a way, except perhaps for the person who plays the victim.

In a dance theatre piece you come in, walk over, take a chair, sit down… Let’s take an example from 1980 – you come on and shout, ‘Fire! Fire! Fire!’ Why? Because there’s a fire and you want people to come. It’s a different matter when you know where it came from, why you have to say that or what was originally behind the question. What was behind this cry, ‘Fire! Fire! Fire!’? At the time it might have been things like: you have someone there who wants to hurt themselves and you don’t want to leave them on their own, don’t want to leave the room. You’re afraid this person will hurt themselves, but you want to call someone. What do you do? That was the question. Important, very important, because then your imagination can get to work. At the time, Pina was there, Jan, Malou, Dominique… For me it was ideal, of course and there was much more time. We didn’t have such a huge repertoire; it was more normal. Today there is much more pressure. Or is that just how it feels to me? I don’t know. Today, of course, many years later, not all of these people are still available to tell the original story.

Chapter 7.2

Sensing and expressingJean Laurent Sasportes:

It’s certainly true that the trust Pina had in me at the time, and my awareness of that trust, really helped me. Because Pina never said, ‘You have to do it just like he did.’ She said to me, ‘here you feel that, and that, and that, and you have to express it.’ And then you understand you yourself have to express it, and not necessarily like the man you can see in the video. As long as the result is authentic and fits, then it’s right. Naturally it’s easier for me to take that approach than to try copying it precisely. This is not to criticise the way it was done later; if you are left on your own to learn something, it’s safer to copy it precisely.

Chapter 7.3

Teaching Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

You played this role in Café Müller for a very long time, then eventually someone else learnt it. How was that – the handover?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

I taught it twice, once with Fernando and later in Rotterdam, Gent and Antwerp, with the Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui company, yes.

With Fernando I did my best, but equally I wasn’t asked the whole time, because, I think, Dominique and Malou wanted to preserve Fernando’s authenticity. He wasn’t to be given too much information from me and then play the role too cerebrally – which I totally understand. I hadn’t been given too much either, because the people who taught me, Dominique and Malou, weren’t people who had performed it themselves. In other words, they didn’t have a trick for how to do it. I can understand that, but naturally it made it hard for Fernando in the sense that he faced the same difficulties I faced. That means that to be truly satisfied in this role, with what you’ve done, you have to do a lot of performances. I don’t know how many performances I needed to reassure myself, and till Dominique and Malou started to trust me. At any rate, you don’t manage that in two weeks of rehearsal. You have to build up the experience. So the handover was as good as possible, but it’s a bit like in life: you can help someone, but you also have to tell them, ‘you’ll have to experience it for yourself.’ I would help up to a point, but not too much. It’s understandable if someone says ‘No, don’t help too much otherwise it won’t be authentic any more.’

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

There the rehearsals were more… I’d had the experience already and so I passed on many more aspects: how the chairs and tables go, for instance. I had gradually organised that tighter and tighter. Not to make my job easier, but when you did a show, at some point Dominique or Malou or Pina would say, ‘There are too many chairs there. I can’t do this movement.’ Then you try somehow to have a few less chairs, to understand why they have piled up – because the choreography is fixed – and then you begin to understand. So after that you organise it so that it can continue to stay spontaneous – but you avoid situations which could be difficult for the others later. That means that if you let the stage hands install the tables and chairs and don’t get involved – assuming they don’t know what to do with the chairs – when you do the show you end up in a situation where the choreography is too badly disrupted. Of course you want to avoid that, for Dominique, for Malou, for Pina, for…, for the audience – you have to ensure the audience don’t end up with chairs falling on their heads. The tendency is always to slide the chairs towards the front, through the choreography. But you have to be careful, because after twenty shows you notice that you always end up with a bit of a wall, which for one thing stops the audience seeing anything, and also… All these things, little bits of information you collect, solutions you find… which of course make it more thought-through, but you just have to make sure this doesn’t damage the authenticity and spontaneity. But if they aren’t in place, you get into difficulty from the start. A new person would have these problems and then it would be a problem for the dancers too.

Ricardo Viviani:

Did you evolve your own particular ritual in this space before the show?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

Yes, not so rigid, but of course, after 300, 400 times. (laughs) It never got routine; it’s crazy, but I never ever felt with any piece by Pina – I performed some of the other pieces 200, 250 times –, I never felt it was routine, otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to do it at all. Malou, Dominique… they aren’t the kind of people either who would accept the feeling it was routine. But the pieces are made so that you never have that feeling, even less so with Café Müller. You slowly set up, when you arrive. At a certain point you arrange the chairs. Dominique is there, in the spot he always warms up in. A little ritual establishes itself on its own, but it isn’t a ritual which is absolutely essential for me. It’s true that Pina always had a particular time when she worked on her movements. And even the same request, ‘Don’t move the chairs over here’. Even after 300 times it comes! (laughs) ‘Yeah, yeah, no problem!’ (makes a reassuring gesture) It was a family piece.

Chapter 8.1

CorrectionsRicardo Viviani:

Given that Pina danced in the piece herself, with her eyes closed, how were the corrections given?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

As I said, Café Müller was a special piece. We corrected each other, on timing aspects. Pina and the others didn’t need to open their eyes to notice what was right and what wasn’t. But also, everyone knew themselves what corrections they needed. At some point later we, or Pina, asked for an extra set of eyes. But the corrections we were given were things we already knew. With such experienced people – from other pieces as well – you knew, you had felt it, sensed it: ‘there I was too far forward, or there I was too late.’ It’s very good to have someone to give corrections – it’s very important – but for a piece like Café Müller you could also manage without.

Chapter 8.2

Pina’s partRicardo Viviani:

On the few occasions when Pina didn’t perform, was it a completely different world?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

Not completely. Firstly because the person who stood in for Pina, such as Héléne Pikon or Anne Martin… Pina didn’t choose them by accident. Pina certainly had something very special, but I would never have thought of comparing; it’s just a good opportunity to notice what was special about Pina.

In Café Müller there’s a moment when I’m behind the door waiting for my next entrance. Then I always watched Pina, walking from her position against the wall diagonally to the front, like this (gestures with hands down), and then at some point her arms were stretched out. I saw this sight a hundred times and the moment was always magical. The older she got, the more magical. You really had the feeling she had no contact with the ground, that she was like a ghost moving through the room, and you had the sense she was about to float up into the air. I have never made comparisons, and never considered it when someone else was doing it, but this ethereal feeling was something Pina conveyed in particular.

Chapter 8.3

Pina Bausch watching Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

On one of these occasions, when Héléna Pikon was playing Pina’s role, Pina saw it from the outside and made a few changes, especially to the lighting. Did you notice consciously how it changed?

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

No, not consciously really. I can imagine what it was like when Pina saw it, because it’s very difficult, in my experience, a piece where you’re the choreographer and you’re in it yourself. Because really you can’t be in both positions. I was so busy with what I had to do.

Jean Laurent Sasportes:

This dance theatre, Pina’s:

My experience of it was as a big family. It’s changed a lot. Of course now Pina isn’t with us you don’t get that sense like in the early days. I had the great fortune to arrive as this family was really starting to establish itself. The company began in 1974 and I arrived in 1979, five years later. It already existed, and had made some wonderful pieces. It was already a family. But it wasn’t too late for me to get the feeling I couldn’t join the family. And we had a different kind of lifestyle. After rehearsals we always went on to the restaurant and talked for ages about the work, the piece, the rehearsals. These conversations have carried on. When I see Malou or Dominique, when I come into the office, as I did a few months ago, it’s as if I was returning to my old family. There are several families like this in the history of performing arts who have shaped that history. Naturally it was because the head of the family was a very special person and the family also became very special. I’m thinking of Tadeusz Kantor for instance, also Fellini and his team, Pasolini and his team. This was an exceptional time in the development of dance and theatre. Of course lots of other people had tried to bring dance and theatre together before. Some of the attempts succeeded, others didn’t. But I think with her sensibility Pina succeeded in making both mutually complementary. The term dance theatre, within which I operate as a choreographer, particularly when I’m making my own pieces – I do a lot of choreography for theatre, and it’s not the same. Choreography for theatre and choreography for dance theatre are two different worlds. – There’s huge freedom in it as to where you can get material from. There are so many different means of expression: speaking, singing, movement, abstract movement too… There’s a huge range between Café Müller and Bandoneon. You see that today too. There is a lot of freedom.

Suggested

Legal notice

All contents of this website are protected by copyright. Any use without the prior written consent of the respective copyright holder is not permitted and may be subject to legal prosecution. Please use our contact form for usage requests.

If, despite extensive research, a copyright holder of the source material used here has not been identified and permission for publication has not been requested, please inform us in writing.