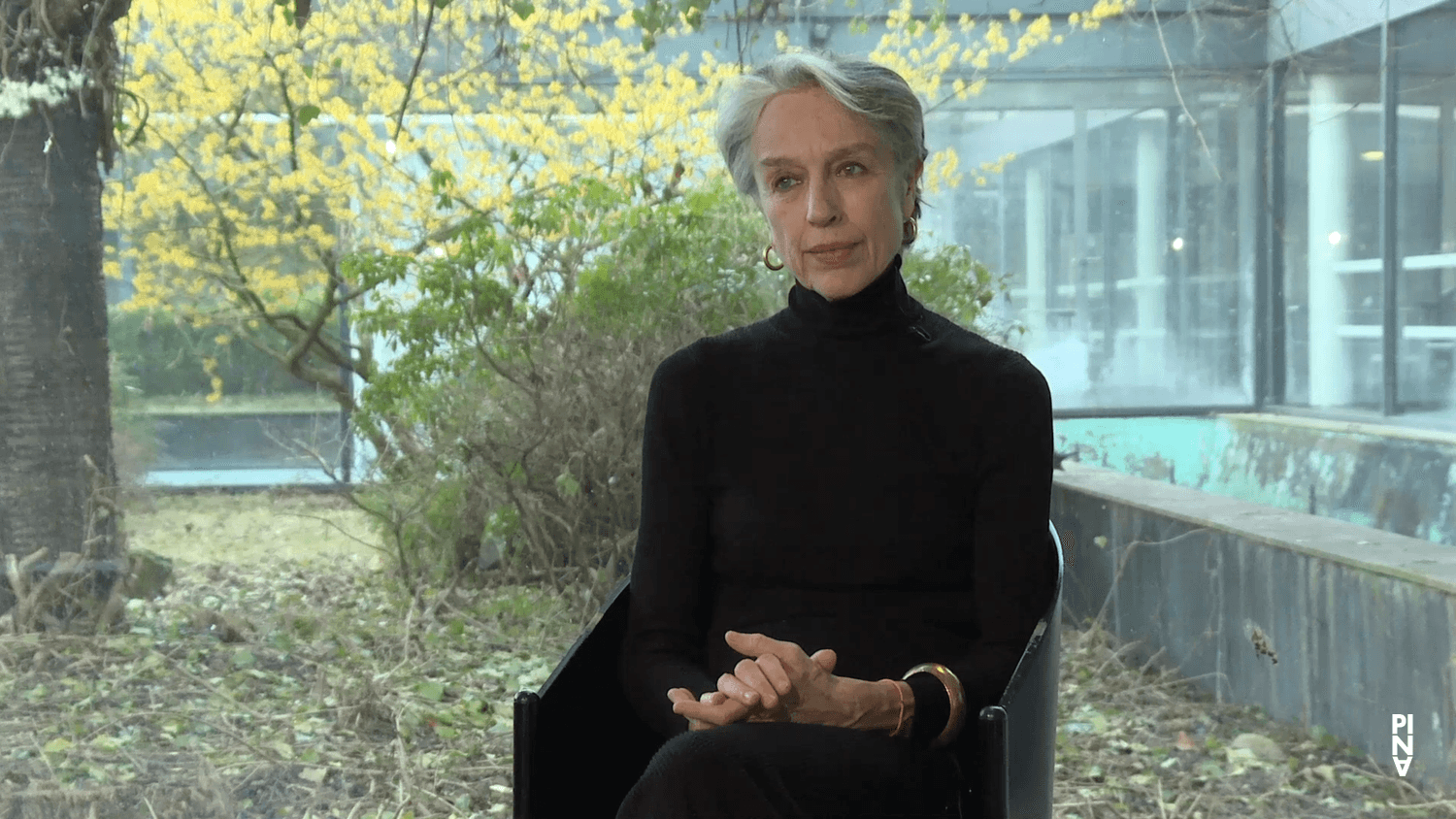

Interview with Pablo Aran Gimeno, 26/9/2018

In this interview, Pablo Aran Gimeno talks about his unique story of becoming a professional dancer, his studies at the Folkwang University of the Arts, and learning roles from the repertoire. With respect to creating new work with Pina Bausch, Pablo talks about his insights of the way the work was conducted. He makes a strong point of how dance legacy keeps being transmitted by the carriers of the flame: the bodies of the dancers that immersed themselves in the work.

Interview conducted in English

| Interviewee | Pablo Aran Gimeno |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Camera operator | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20180926_83_0001

Table of contents

Chapter 1.1

BeginningsRicardo Viviani:

The beginning is a good place to start. So maybe you can tell us about your coming to dance.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

I was born in a little town out of Barcelona, in the periphery, in the suburbs. My sister got a visit. She was 18 years old, working in a perfume shop. The owner of a dance academy came one day and asked her, ‘Among your costumers do you know someone, maybe a lady, that has a boy or a girl?’ This dance teacher was planning to open a course for ballroom dance initiation for children. So this dance academy teacher went to buy some perfume and asked my sister, ‘Do you know somebody that likes to dance or maybe has some children at home? I am looking for that in this little town.’ And my sister said, ‘Ok I will tell you, but I know already one person who will love that.’ And that was me (laughs). ‘My brother, he moves a lot and he likes to move and to make playbacks at home, with music.’ The dance teacher said to my sister, ‘Take him one day, we'll see.’ I was ten years old. When my sister came home, she asked my mother, and my mother said ‘Oh, but maybe it's too soon,’ because this dance academy was outside of this little town, where all of the factories and industrial complexes are, all industry and big halls. I said, ‘No, I can go mamma. I can go on my own.’ And then she said, ‘Ok let's go.’ It was on Friday from 6 till 7:30, one and a half hours, once a week. They allowed me to go and I went. That was my very first contact with dance, of something with music, and movement, and rhythm with a more educational side, not just at home having fun. I really had fun in this place too, but that was the very, very beginning. On top of that, of course I was growing up and at 11, 12, 13 years old some jazz classes came, maybe a little ballet, but just in this little town academy. But it was at a low level, just for fun. Also ballroom dance became very big for me. I stayed in this school for nine, ten years. When I was 19, 20 I was still in this place. I became a ballroom champion and did all the championships with my partner. I became a Spanish championship winner. I went really far with this thing. It was also the boom in Spain in the 90s, when ballroom dance got really, really… In the UK and Germany it was already very known, but it got very strong in the 90s in Spain. So the school I was learning at became very strong with a lot of people following that. So I became that: a ballroom dancer. That was my beginning.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Then what happened was – that was until 20, 21 maybe, and I had had two ballroom partners at the time. And then I thought; ‘Ok that’s not what I want. I want to dance. I want to see myself in a dance company, or I want to see the stages, and theatres. I don’t want just to do this very kitschy thing, very commercial thing, with the dresses and everything. It’s very fancy, but I think I need something deeper, something more introspective.’ So I got very interested in academic dance, classical ballet, contemporary dance, dance that was more individual or group, not with just one partner and showing off. So I went to Barcelona, I began to take ballet classes more frequently, also modern, jazz. I was there at 21. Then at the age of 22 I decided to continue in Madrid. So my first jump was from the village to the city, Barcelona, and then after one and a half years I decided to continue my education in Madrid, in the conservatory. I signed up for the ballet career, although I didn’t want to become a ballet dancer; I thought it would be nice to have real knowledge of it, just as information. I was also taking some contact improvisation classes, some contemporary classes, sometimes modern classes. It was a very fruitful stage in my education, after leaving Barcelona, these two more years in Madrid. Then I had the chance to escape one little week from the studies and I went to Paris. There was Le Cartucherie from Carolyn Carson; Malou Airaudo was giving a workshop. So I went to the workshop. Then when I did the workshop, she asked me, ‘What are you doing? Where are you?’ I said, ‘I am in Madrid. I am studying ballet, contact improvisation.’ She said, ‘Why don’t you come to Essen? Maybe you’d like the school and you can continue your studies over there. So you can pass by one week and see.’ That was in March. I went in May 2005.

Chapter 2.1

First Pina Bausch pieceRicardo Viviani:

Up to that point, had you seen any performances by Pina. What was your first?

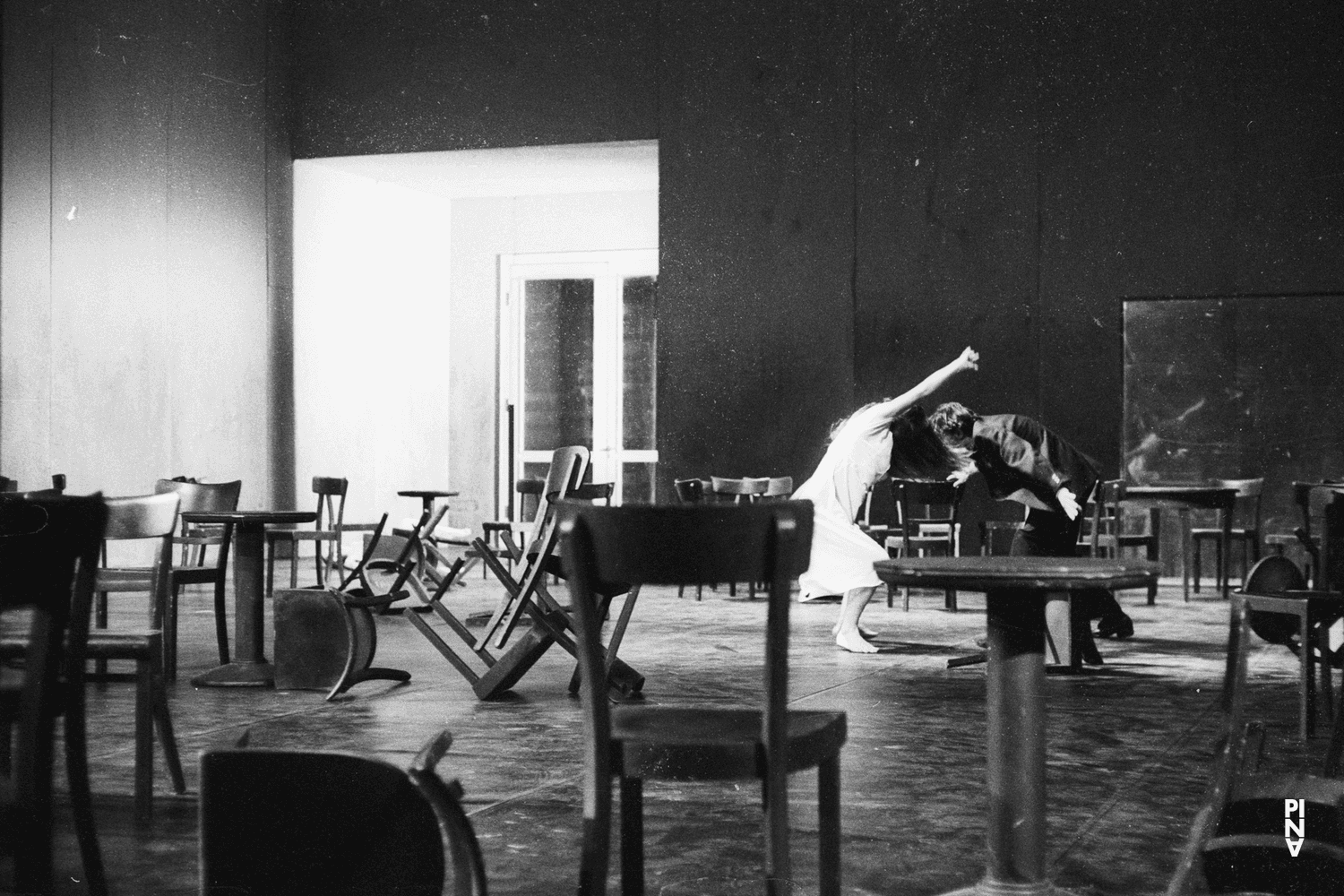

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

I saw Pina in 2004 and 2005, in Barcelona, Teatro Nacional. It was Fensterputzer and Für die Kinder von Gestern, Heute und Morgen. Also I knew things by Pina because one contemporary teacher in Barcelona, before Madrid, he showed us Café Müller, Blaubart and many things. I saw a documentary about Dominique. He was really in love with it. It became something interesting to me, especially when I went to Madrid. When I quit this Barcelona class and this teacher all that he said became bigger in Madrid, maybe because I had no daily conversations about it; it became kind of a myth, or something, what he told us about the company and how he knew about the work – although he never worked with the company, but he liked it. That information, and curiosity grew, then I went to this atelier with Malou in Paris, and it became clear, ‘I am going to try.’ I also liked Carolyn Carson, DV8, other things, but I thought, ‘I am gonna go. I am gonna try.’ Anyway I had to continue my education. I was willing to stay one or two more years in this vibration of education. I did so much ballroom dance between ten and 20, delivering constantly, giving classes, performing. It was a lot of showing-off. I wanted to re-nourish again, feed back. I thought, ‘You did one and a half years in Barcelona, two years in Madrid, one or two more years in Germany would not harm you.’

Chapter 2.2

Folkwang HochschulePablo Aran Gimeno:

Then Malou invited me to go for one week in May. I went to the school, I liked it, and I thought, ‘Ok I’ll go.’ The director of the conservatory in Madrid was super understanding, and she said ‘Go.’ She offered me the possibility of doing my last two years in Madrid at a distance; I had to come back to do my exam at the conservatory. So that May I came back and said to the conservatory, ‘I am leaving,’ and in August 2005 I was packing my things to go to Germany, to Essen. While I was on the highway – I had to do a little stop in Barcelona to go to Essen; one of my flatmates from Madrid was driving with all of my boxes from Madrid to Essen via Barcelona – I received a message from a close friend, she says, ‘You know that Pina Bausch is doing an audition? She is looking for two male dancers. You are going to the school but maybe you’re interested.’

I was like, ‘Wow, OK why not.’ So when I arrived, the audition was one week later. I had to be in Essen on September 8th or 5th; the audition was on the 12th. I thought, ‘Anyway I have to stay in Essen one or two years.’ They asked me to join the 3rd and 4th class out of four years of Bachelor. I thought, ‘I’ll do the audition, try my chance.’ And then Pina took me.

She knew I was trying to go to the school, so she said: 'I know you are in the school. You can keep learning The Rite of Spring with Ed Kortland and Malou,’ at the time, supervised by Lutz of course, ‘You can take the classes. You can come to the company and begin to learn some roles with Alexandre Castres and Fabien Prioville,' some from Alex and some from Fabien, because Alex and Fabien were leaving in that season. So I did. I was supposed to begin season 2006/2007, so I had the end of 2005 and the first 6, 7 months of 2006 to prepare myself. But in between already something got mixed up; Daphnis Kokkinos had a hernia operation and somebody had to replace him in Keuscheitslegende, the Legend of Chastity. So then she asked me to join this piece, which Bernd was doing at the time, before Daphnis. And before Bernd – I don’t want to make a mistake, but I think it was maybe Ed. I am not sure. Also she asked me to do a tour of The Rite of Spring in January, February and March in Brussels and Japan. Then came Legend of Chastity, premiere April/May maybe. May/June 2006 was Ten Chi already, also in that period Fensterputzer. I remember because it was all of a sudden, all this information: Rite of Spring, Keuschheitslegende, Fensterputzer and Ten Chi already for the next months. And I was learning Nefés for Alex.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Yes, it was very funny, because these pieces, Nefés and Ten Chi, I wasn’t in the creation, but when you look at the year that the creation was made and the amount of performances, the original role, Alex in this case, and after that, these thirteen years, the amount of performances I’ve done, it is not my original work but I feel it also belongs to me – it’s not mine, I don’t own anything.

Chapter 3.2

Learning processRicardo Viviani:

That’s a very important, interesting point. Maybe we can stay there a little, and maybe talk about Nefés since it is a role that you identify yourself with – just putting it in other words. Did you first learn from him? How was this process? Did he talk about the questions?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

No, he showed me. Alex is a beautiful dancer and he was so generous. He was leaving the company but he was careful with me. I still appreciate that a lot today. He’s somebody I like a lot. He released his information to me; specially with him we did Ten Chi and Nefés. And the same goes for Fabien Prioville. He was teaching me and Damiano – we came into the company together, Damiano Bigi –, he was teaching us Masurca Fogo, Kinder and Fensterputzer, because he was doing the role of Michael Whaites. So in this case, in Nefés, Alex was showing me the movement, also transferring information about the movement – why that movement was maybe a certain gesture, inspired by some action, random daily action, or here you’ve got a rope and you pull it, or a gesture, or you hit someone with your head: information about the gesture, the movement. Also sometimes just lines and forms and shapes and where it’s coming from. The origin of the movement, also. I must say from my side it was with a lot of pleasure. I was very hungry.

Chapter 3.3

Video tape as sourceRicardo Viviani:

Did you work with video at that point? Do you have a sense of how the video was used?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

It was not so present, because they were there, they were showing me, and I was doing it and they were looking at me. Maybe later, at a middle stage or late stage, we’d look at the video maybe once or twice to see the dynamic, or some precise concrete detail about something that wasn’t working quite so well. For that the video was necessary. Later on, after so many years I had some moments when I had to learn something straight from the video because the person was not there, not able to come, and I had to prepare myself from the video. Then the person came and checked everything; so it was the other way around. With Alex and Fabien it was flesh. It was real.

Chapter 3.4

Integrating with the othersRicardo Viviani:

And the group dynamic, from learning the role to being in the group, did you have enough time? How was that integration into that sort of energy of the performance?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

I think I was very lucky. I felt I had time to prepare myself. I don’t know why. I don’t know what amount of responsibility I had with that. I like to repeat and repeat, and try and try. I am a crazy one. But also there was physical time. Also the original, or previous cast, was willing to help. The synergy between my hunger, their commitment and also the schedule provided enough time for the quality, even though I don’t think I was prepared for the first performances. It took me longer, and even today I feel that every time you have to understand that something new can be improved, but to feel that I’ve got something, much later than the first series of performances, second or the third. By the third maybe you feel, ‘Ok that move is mine now,’ – not mine, I don’t own it, but it is something I have to defend. And I do feel responsible for that.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

For me it was amazing! (laughs) I was really happy. Maybe I wasn’t in my best moment, because it was all this struggle of coming to Wuppertal and beginning this new process; it was not happy. But in another way, on another layer, of course, I was very motivated. I was highly motivated.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Maybe for other colleagues it was one more process, but for me it was the first time I did such a process with such a choreographer. I really enjoyed it.

Chapter 4.3

ChallengesRicardo Viviani:

Let me put it in another way: what was really challenging? What was the big challenge in this creation for you?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

To work with a group of people, in that way. To work with this amazing company, to find myself within it. It was like, wow, a lot of questions, on identity and who are you, where are you, why are you here, is this really happening? To update myself, and to understand and to make choices, how do I relate to this place, because it’s new. But not only because it’s new, because the place, what it is, is already an extra information. To understand, to keep it low, simple, humble, easy. To try to do my job, to get to know the people. To find my place in the company in the beginning was not easy. I know she liked me and I liked her. That’s ok. I don’t know how it would have been, maybe ten years later, if she were alive, maybe we would also have had these conversations you have with your director. There are sometimes… (gestures: confrontation) I didn’t have that. It was only four and a half years working together, so I had only the honeymoon thing, in a way. Also her age, my age, was another circumstance in comparison to the 70s or the 80s with other former dancers: very strong conflicts, or maybe not. I don’t know. In my case it was very easy. I was very motivated, but at the same time that created in me a lot of difficulties to find my place. I don’t know how to explain, but maybe to feel you are worth it for such a place, because it’s full of these strong personalities, and the work is so overwhelming, and the amount of work, the rhythm of work, of rehearsals, and the quality was very present all the time. It needs to be. So you’d better work, and you’d better get prepared for the group rehearsal. Of course, in the first rehearsals the people are also watching, ‘Who is this boy from Spain? Why Pina took him?’ because Pina was not used to taking ten people at once, at least in my time. Maybe two people came in, maybe later one person comes in, maybe two or three, then no-one, the next season one person. It was not like waves of people migrating to the company. So in a way you better work and deliver what you will be asked for. That’s maybe the thoughts of a 22/23-year-old dancer that wants to be good. It was challenging for me.

Chapter 4.4

IdentityRicardo Viviani:

Learning repertoire you are placing yourself in the place of some other performer that was there before, and during a new creation, as you say trying to find your place in the company, does that mean for you, also as a performer or as a person, finding your stage identity? In the sense: what do you have to add to this mix? What did you find out?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Absolutely. Femininity. Very funny: femininity. Very strong. I am not talking about movements; I am talking about a way of working. A feminine way of working.

Chapter 4.5

Discovering a way of workRicardo Viviani:

Can you maybe describe that? Or give an example?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

The way to say things. Maybe I am making a statement that for some gender theory or queer activists is confusing, but I think it is something that has to do with femininity, regardless of gender, and I found the way of talking to people very interesting. It’s very surprising when someone is working with you for 30 years, but every time this persons addresses you, speaks to you, talks to you in a way that looks like it is the very first time this person met you. That I think is something very German also, all this oil between the years in terms of social behaviour, very north European, very polite also. Keeping a distance, which you appreciate, because it can make daily life easier, but also you could feel the choice of every person, those dancers, was not a choice you should take for granted; this lady wants this person to be there forever. That’s why this person was chosen as a dancer. So the way to speak was with a high amount of respect and love. Of course [among] the thousand stories of all the people they could have had issues and problems and again I could imagine I could also have had issues with Pina and the work, maybe later on; that was not my case. What was just my experience, what was impressive, is, ‘Oh wow!’ you couldn’t see the whole story between these two people, you could think they’ve known each other since one month, or one week. The way of addressing, asking for the movement, so really focussing on the movement, focussing on the work, trying to keep aside many stories and things, with maybe a silence, a look... Of course this is also maybe a flair or something, but for me it was very impressive as a way of working, certainly a freedom. Freedom plus respect plus care for relationships, that is something I relate to femininity. That’s also something a male gender could have. It’s not about that.

Chapter 4.6

Gender and BallroomRicardo Viviani:

That’s interesting. We are talking about something that is more than ten years ago, and these are things that today are very much in the foreground, the fluidity of gender – of course in Pina’s work it was always there. In ballroom dancing these roles are set – or not? Maybe you can educate me.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Yes, it’s a stereotype, absolute cliché, a stereotype of the man and the woman, the way we have been educated about it.

Chapter 4.7

Personal journeyRicardo Viviani:

Does that mean, and now comes a question, that Pina was able to be a catalyst in this discovery, or in this journey?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Yes and strangely without being so active. She was not maybe the New York or Berlin choreographer, shaved head going for that ‘Let’s talk about that. Let’s talk now about what is going on in our society.’ But in a way she was contributing through her work, and she was also talking about gender, and male and female, and men and women. But in a way I just remember me wearing a dress, of course inspired by all of the times in the pieces of Pina that men are wearing them like Two Cigarettes in the Dark. I thought, ‘I am going to do something,’ and she asked me for a keyword: ‘Beauty.’ Then I created a phrase with movements, and it was like writing the word but inspired by movements of my colleagues, my new colleagues: Nazareth, Azusa, Ditta, Helena, Aida, Julie Shanahan, all the people. I was very inspired. And I did that phrase with a dress, and she liked that, and she asked: can you develop this and make it longer, and it became a solo, but she said, ‘just with weibliche Bewegungen', with feminine movement, and so I did. But at the same time in another day in that creation I went and I did just a stupid thing and I say at the end, I said ‘I would like to be a man. A real man. One day I will be a real man.’ And she said to me, ‘Du bist doch ein echter Mann,’ – she said, ‘you are a real man already, what do you mean?’ She was, in a way, very naïve, or maybe not interested in being a super transgressive artist. I had the sensation it was naïve, but not because she didn’t know anything, but in the sense that she was coming back from all that. She found it selbstverständlich [self-evident]: ‘of course you are a man and of course you are feminine also.’ She didn’t have any reaction about it in a way.

Chapter 4.8

Growth in differencesPablo Aran Gimeno:

I don’t know. I myself, in my education from my parents, I never had problems with my sexuality or with my artistic practice, or my choice to become a dancer. This, in my country, in Spain, can still be very difficult for some people. South European countries specially, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece. But it was good to get that also not only from family or friends, or teachers, but also from her, and give all these issues an artistic shape, a movement.

Chapter 5.1

Iphigenia in TaurisRicardo Viviani:

…a role that became actually also very important in Iphigenia – can you tell me about how you came into that role and how the whole process was?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

That was in 2008. She asked me to learn Iphigenia. It was premiering April 2009, if I’m not wrong. Maybe I’m wrong; it was a little earlier, but it wasn’t in the very beginning. It was one and a half years after my arriving. And she said, ‘I am thinking about remaking this piece again, because Dominique is not going to do it and I asked him, and he and Malou, and we thought you could learn it.’ So I began to work with Dominique, and that was very interesting also, because I knew Dominique as a student a little bit, but also as a member of the company, but I hadn’t worked with him so closely. And it was a very nice experience. We began to work together.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

One person to the other, maybe in the very beginning there was also Ruth coming for some things, and also Bernd was coming to help me. Also there was Aleš Čuček learning – he is not in the company anymore –, a dancer from Slovenia. Then he got out of the process, and we focused with Dominique, and there were a lot of sessions, one to one. Sometimes there was Fernando Suels coming, because he was replacing Bernd. But many, many times it was one to one. Actually for me it became something beyond the piece itself. It became learning some principles and some basics about the work. Dominique said, ‘We need to work on some things that are not only for that moment in the piece, that step; you will apply this in all the movements we are about to discover. We are learning the piece, maybe we are now in the first act, but this is not only for this act; we need to focus and go deeper. Don’t worry if we don’t get to the fourth act next week, because then it will be much faster. First we will focus on the second act. We work and go for the qualities, and maybe later the third and fourth act will be very fast. It’s only steps. By then you will already have the qualities you need to apply later.’ And actually that is still here today. (gestures: points to the back of the head) It’s very strong.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

How to work with my shoulder blades, how to work with my wrists, with my fingers, with my hands, how to breathe, how to use the chest up, the chest bone, inside the high arch, the second isolation, the high contraction, how to work with the pelvis, how to work with the knees when opening a second position, how to use the weight, how to go into gesture and the sensitivity, the amount of intention in everything, especially if it’s recitative in some pieces, especially Iphigenia, where there’s a lot of talking in the piece, not only singing, or singing and it’s a lot of recitative. So almost no movement, minimal. How to be in this place. Technically, but also, as a performer. All of these examples. (laughs) That was very strong, not only for that piece, but also I worked with Dominique on other pieces. But in general it is something that goes beyond the pieces, beyond Wiesenland, Agua, Two Cigarettes, Iphigenia, all these pieces, Masurca Fogo; it goes beyond that, because that stays with me. So I am not owning any of the material, not from Pina, not from Dominique, I am just a channel. I am very aware of it. But at the same time the rewarding thing is, I am getting this information for my own practice: the way of working. It’s very interesting. I really like a lot – and this I relate to the work that Pina liked that comes from, of course, Züllig, Jean Cébron, Kurt Jooss, the Folkwang, all of this heritage... I always make this comparison, when I see Bernd, when I see Rainer, or I see Ruth, they have this very strongly, of course, many people from the school, from Essen, this big strong period between the late 80s and 90s. So strong, so clear, so beautiful. So of course Dominique has that, of course. There’s is a whole language about that. This is what I take through these overtaking roles with Dominique, or whoever – especially with Dominique. With Aleš and Fabien it was more like, ‘OK, I am discovering myself. I am able to do a flip. I am able to go on the floor that way.’ Also you learn a lot with Kenji. Kenji is like a mixture between this experience I am talking about, Fabien and Aleš, and the Dominique experience, because I can also discover through Kenji new qualities like Fabien or Aleš. ‘Oh, I can do that also.’ It’s another way of learning another language. But at the same time Kenji also has very strong basic principles about the work of the Folkwang – you can see; I can see that. He has a very strong understanding for that. Then it’s also a way of learning, ‘OK this is the right amount of energy I have to give for that movement,’ or, ‘that can also be possible,’ I don’t know.

Chapter 5.4

Meeting the mastersRicardo Viviani:

Did you ever meet these other masters, Jean Cébron or...

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Not yet – well not yet! (laughs) Cébron, he’s still alive. Herr Züllig I never met, nor Alfredo Corvino. When I came to Wuppertal, he died, that same year I came: 2004 or 2005/2006 he passed away. Pity. But anyway I feel like then for my generation Cébron, Züllig and Corvino would now be Lutz, Dominique, Malou, these people, this generation, if they are willing, that would be where I would look for this knowledge. I would go to them, of course. Also Jean and Nazareth. Nazareth for instance, she's very strong also in this language, very strong. I remember because I also took a workshop with Nazareth, but because Malou already taught me that thing… Nazareth was actually back then. When I was talking in this interview about my atelier in Paris with Malou, that was spring 2005; maybe it was March or April. In the same period I took another one, a little earlier, before Malou in Paris, and it was Nazareth in Spain. But then I didn’t dare to ask anything and also she didn’t say anything. I just enjoyed it. And you can see, when you see Nazareth working, you see this language also.

Chapter 5.5

A flow of informationRicardo Viviani:

Before we go into Café Müller, is there anything you would like to add to those early experiences, or in general?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Not really, because there are so many things I would say. I feel I am full of information that doesn’t belong to me. I am full of information just by the fact of being 13 years in this place, so if we speak about things, I just deliver. It is kind of flowing out. (laughs)

Chapter 6.1

Tanztheater in BarcelonaRicardo Viviani:

Café Müller. So you were already familiar with the video, and then in your first years in the company there were some performances, also Pina’s last performances in Barcelona. Do you remember that one performance? Was there anything unusual about going back to Barcelona, and living through that experience now in Barcelona?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

I wasn’t performing in Café Müller that time. I was doing The Rite of Spring and then we came back in 2010 with Iphigenia. But 2008 with The Rite of Spring, of course, was the first time – after Madrid with Nefés –, Barcelona was the first time I came to dance this piece in Barcelona. It was really nice. For me it was more special in 2010, with Iphigenia, because there it was really ‘from me to you’. Rite of Spring is a big group. Of course it was important, but it was more, like, a group. But then Iphigenia was one piece in one evening programme, and it was me doing the role of Dominique; it was a kind of zoom in. So I could then feel more engaged and related to the city and the fact of me coming back to the city.

Chapter 6.2

Memories of Café Müller performancesPablo Aran Gimeno:

But I remember of course Café Müller in Barcelona and I remember Café Müller in London, because she had a little issue with her health and she did not dance one evening, or more than one evening, and I remember it was strange. I also remember Café Müller when she danced in Lisbon, Lisboa; they danced in Teatro São Luiz, very small theatre, and there I went to watch. And that was the first time I saw Pina dancing Café Müller.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

After all I explained to you? It was no wonder; it wasn’t so surprising because I had already experienced working together, and I was inside; I had a very strong connection with her, in a way. It was, ‘Ah, oh, of course, I know she can dance.’ But that’s the same as seeing her directing a rehearsal, or being at the theatre giving notes. It’s also a performance. It’s like a show.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Not so long ago, just last year. They asked me, one year ago maybe, one and a half years ago, but then at first they weren’t sure. They didn’t have the need to replace. It was just learning and watching, but then one year ago we went to New York in September, The Rite of Spring and Café Müller, and Fernando Suels was replacing Jean, but he could not come. So I had to do the performances and that was my very first time doing Café Müller. They asked me to learn Rolf’s part – Jean –, doing the chairs.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Very funny. I was coming with my bike, and I thought this question, how did I learn it? Nobody taught me. (laughs) I knew the patterns, the ways; Fernando gave me the paths on an A4 paper, and then I saw him doing it, but then because they had a lot of changes in casting – first it was Dominique, Lutz and Malou working, but then once Lutz went away, there was Dominique directing, Malou also watching. Last time it was Dominique, and he said, ‘You know the paths, and you just try to sneak in and do it. We will see, we will work later.’ We never worked. (laughs) It’s just me kind of knowing the ways, and trying to adapt to what is needed to put myself at the service of what is needed in this moment. They were focussing on Malou’s role, which is Ophelia or Azusa, and Dominique worked with Jonathan and Scott. Of course Blanca and Nazareth, Michael and Michael, all these things had to be connected, and then there is Pau, with this A4 paper, knowing the paths, because Fernando told me, because Jean told Fernando, Dominique supervising, but at the same time everybody asking me, ‘maybe that’s the way,’ so I learned thanks to the colleagues, Dominique and the colleagues, because they were asking me what they needed, maybe watching a little bit some video, some detail – very strange, in a very organic way that you don’t realise but you are doing it. It’s like, ‘Ok, so now it’s a run through.’ ‘Ok, let’s do a run through.’

Chapter 6.6

About caring for the people on stagePablo Aran Gimeno:

Because this role is very practical and human. It’s not about dancing movement. It’s not about that. It’s about taking care of the space and the people, holding the space for them, in a way. And that I like a lot. Because also again it opens up a door that since many years I have been willing to open, this door of being on the stage, being in the performing space, but in a less performative way – a more realistic way.

Chapter 6.7

Floor patterns notationRicardo Viviani:

We’ll come back to that soon, but I’d like to dwell a little on this A4 paper. What was that?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Yes. (laughs) Of course, they tell you enter this way, and then you have to do that diagonal, and then you go here, you go here and you go out: (gestures: showing lines in the air) first entrance. Second entrance: there’s a cue, you go with Scott – which is Dominique – and then you run – or Jonathan – then you need to take care of that table, and then he makes this, then he runs and you go. So just the structure. But the reality is, then GO.

Chapter 6.8

NotationRicardo Viviani:

Were, like, lines drawn into this paper? And those cues? Is that what was there? My question is about notation.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Yes, also, but it’s your personal interpretation of it. When they explain to you, maybe you write down with your writing: ‘cue number one, tat tat ta,’ then you make a little map, with a little puppet, you put yourself how you need, how you want. From their end was more verbal transmission. It was not like they were giving me a paper, with something that was in the Regiebuch, the direction book.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

I got the information, and I did the A4 paper. Fernando, what he did for instance was also his own notes. He just explained to me and I took my own notes.

Chapter 6.10

Genesis of the pieceRicardo Viviani:

Do you know about the genesis of this piece? Tell me what you know.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

What I know is that this piece was made in a very small amount of time. What I know is that project was not only for the company. There was other people involved, other companies or groups involved, and they all had to present a piece based on the same idea. Also, involved in this idea, frame of an idea, there was a red wig, chairs, and maybe one or two more things I don’t remember. And they did their proposition, and that proposition became what it is. That’s what I know.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

Yes, I remember. Who told me that? Malou or Dominique? Yes. I think they told me that it was so empty, that then they thought, ‘Ok we will put some chairs.’ But then they were complaining, some issues with the chairs of course, then Rolf said, ‘OK I'm going to take care of the chairs, don’t worry. You guys do what you need. I am going to take care so you can continue this thing. I will take care of the chairs,’ in a very kind of, to me, it sounds like a random, spontaneous way. ‘OK, so you have an issue? I am going to solve the issue.’ I don’t know if that is true. You know sometimes information, through years and through people, it changes. I don’t know. That’s what I think I know from this piece. I don’t know that much about this piece.

Chapter 6.12

ApproachRicardo Viviani:

What is useful to you, when you go there and you start dealing with this issues of the chairs, of dancers, in the piece? How do you approach it? It can be very simple…

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

How do I approach? You said it, you named it. Trying to be simple. Like entering the space, as humble as possible, as honest as possible, deconstructing all of what I know. Being there as a human being. That’s all.

Chapter 6.13

ChairsRicardo Viviani:

And how do you relate to those chairs? Are those chairs, sort of, your room, or is that a room you find? Do you check the chairs before, do you know where they are?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

When we did it one year ago in the US, I had a big problem with putting the chairs in a certain way, in the very beginning. So at the end I decided to let Dominique and Bénédicte do that, also the technicians, because I thought they might know better than me. Not because I was lazy, because I thought, ‘You don’t know this piece that much, so let them do it, because they know what it needs to look like.’ Also the technicians they knew better. So I did that. Normally, I am supposed to do that in the very beginning. However I don’t take the space as my space. I just focus on the dancers. I focus on them. I really don’t want them to be in trouble or hurt. That’s not only because they told me to do so; it’s because I really feel that. To stare and to project the gaze, to look, and to be with them, to take the space, also. Yes, space holder.

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

No. It’s a very pleasant thing to do.

Chapter 6.15

Further performancesRicardo Viviani:

Do you know if there’s more coming to you? If you’re performing it again, do you know that?

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

I will perform it now. In October/November. I have to share the role with Fernando. So he does half and I do half. I am open. I am willing to continue. It’s a very nice – moment.

Chapter 7.1

Final thoughts about legacyRicardo Viviani:

I’ll bring it to a closing now. What is Tanztheater? [dance theatre]

Pablo Aran Gimeno:

For me: for me it’s a very strong departure point, that I feel like that’s my artistic family. That’s home. And as always, as every home, you can have beautiful moments, you can have terrible moments, you need to make a process of going away and detaching yourself from your parents and your brothers and sisters, and do your life, but at the same the time, every time you come back you can have a nice time. Also you can sometimes have a difficult Christmas. It’s like that. Highs and lows. But it’s like an artistic family. It’s a place I come back to regardless of everything, despite of everything what happens, everything that is happening, everything that will happen. Thirteen years of my life, I don’t take them for granted. It’s a very strong influence in my practice. Sometimes I go to places and work with other people, or give classes, or dance for other choreographers, and they ask, ‘Oh wow, the way you are, the way you do!’ and of course it’s the way I do, the way I am, but this is also the way my parents, my friends, my history, and the people from the Tanztheater, the company of Pina, influenced me. So it’s not my own achievement. So Tanztheater is a very strong part for me as an artist, in my artistic practice, but also as a human being, because I learned many things, from these people, so for me Tanztheater Wuppertal is a very strong leg as an artist but also as a person, and it will stay so whether I like it or not, whether time goes by. What will remain is a huge amount of time, the last thirteen years, being in this little town and finding yourself alone, with a lot of dilemmas, conflicts, personal, private and also beruflich – working life, professionally speaking. A lot of experiences, a lot of things, so everything is like a hotpot of memories. So the moment you take the flight, and you roam, it’s like you carry a little bag with your memories or like your little flag. So you belong to this lineage, and to feel proud of it, to feel powerful, and to say, ‘Yes, [there are] many other ways of moving, many other ways, many other people, many other directors, choreographers’ – how many languages do we have in dance, in this planet? So many. ‘But this one, I try to take care.’ If not in a practical way one day, at least in what remains in my heart and in my memories. That’s the company for me. Also strangely feeling people that I did not know, but were related to the company as artistic ancestors, like Jo Ann Endicott. I barely worked with Jo Ann Endicott, maybe when she came for a certain period, again: Pina asked her. So we did Komm tanz mit mir, we did The Seven Deadly Sins, in Kontakthof she was also engaged, and so on. Now she came back also for Arien, but I was not there, I mean of course I have a direct relationship with Jo Ann Endicott. The other day I was watching the video of Walzer online, because I wanted to show something to someone, and she was there in this TV screen, and they were like, ‘oh beautiful!’ ‘Yes this is from the 70s and the 80s and all of these people are so meaningful to me and to the history of dance.’ I am so proud I met her, I could work with her, and even if I don’t see her, she remains in my dance DNA and I have so much to thank about, but also her and of course Dominique, Nazareth, Jean, Malou, all of this generation to me is like – same thing for Jan Minařík and Beatrice. I don’t really know them, but I have seen them in videos, and I’ve been in this place, that they also built up with Pina. In a way those are my ancestors, at least so far. Maybe today I will change my language and I will go for another thing, and maybe ten years later, I can speak differently about the new place. But so far, this has been everything I got. Inside and outside.

Suggested

Legal notice

All contents of this website are protected by copyright. Any use without the prior written consent of the respective copyright holder is not permitted and may be subject to legal prosecution. Please use our contact form for usage requests.

If, despite extensive research, a copyright holder of the source material used here has not been identified and permission for publication has not been requested, please inform us in writing.