Interview with Fernando Suels Mendoza, 19/9/2018

Fernando Suels Mendoza’s background as a dancer in Venezuela reveals surprising connections to the legacy of Kurt Jooss. He was a dance student in a time when Pina Bausch was already an influence in the dance world. The topic of legacy is very strong in his interview. He describes how he was coached by Jean Cébron and the connections of this legacy to the work at the Tanztheater. Fernando Suels Mendoza danced in nearly all of the repertoire. He talks about the process of creation from the point of view of the constant search.

Interview conducted in English

| Interviewee | Fernando Suels Mendoza |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Camera operator | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20180919_83_0002

Table of contents

Chapter 1.1

Interest in and pursuing danceRicardo Viviani:

So we start at the beginning, it’s usually a good place to start. Studying dance, a native of Venezuela, how did you come to all of this.

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

I started in Venezuela in ‘87. That’s the year I started to dance. I was 19 when I started to dance. I was doing some theatre before I started to dance. I was dreaming of becoming an actor, and I saw some street performers from some theatre groups in Caracas, and I was really impressed by what I saw. I liked the box and how they were playing in this little box. I thought I’d like to do something like that, so I started to take some theatre lessons, and visited different groups, and workshops, and in one of those workshops I was in a production with some dancers, and I was very impressed by them. At the same time I saw again some street performers. That’s very common in Venezuela, people who have companies or groups, because they receive money from the state, they need to do performances on the street a couple of times in the year. So I saw some companies in the street. Ballet companies, more modern companies. I was very impressed and I thought maybe I would like to go to a dance class to see what would happen. And that was ‘87.

Chapter 1.2

Dancing in CaracasRicardo Viviani:

When we are talking about Venezuela, are we talking about Caracas, the capital of Venezuela? Then you went to a dance class, a ballet class?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, I was in Caracas. Actually a modern class, a Cunningham class. Actually it was very funny because this person I met, he was a classical dancer and he was also dressing as a classical dancer with the tights and everything. I thought it was incredible what they do, but I didn’t want to wear what he was wearing. And it was more about how he was dressed and he said he wanted to bring me to his ballet school. I said no, no, I don’t want ballet. I didn’t know exactly what was the difference, but I knew it. I saw some ballet, and I didn’t like the costume much. Then I saw some contemporary work. I remember one of the first pieces was a duo with two guys, and they were playing two drunk people. They had the bottles and everything; it was so funny. I liked also that they had street pants, normal pants. I thought, ‘I like that more. I don’t want to have these tights on my legs. I want to have the pants.’ He recommended me to go to this school where they teach modern dance. Some of the names: José Ledezma, the company was Taller de Danza de Caracas and Escuela de Danza de Caracas. I went there for the first time; it took me a week before I registered. I was studying journalism at that time. I was at the beginning of the studies. I remember, this friend brought me here one time, I said ‘thank you very much.’ And for a week I was going every day, but I was very shy. I couldn’t take the step to say, ‘I want to come and take class.’ I was going for a week, every day. I was looking around, and at the end of the session of the class I left and I didn’t tell anybody anything. I didn’t have the courage to say, ‘OK I want to come and register.’

Chapter 1.3

Institutional structureRicardo Viviani:

At some point you did. There was no audition, or entrance [exam]?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

No, it was a school, and the way they function is not like a year school. You are there you study and once you get there, you are there and you continue to study. It was non-stop. They work all year long. So after the week that I was looking I decided to step into the office and I said, ‘I would like to do something, take some classes.’ So I did the registration then I started to take classes. That was July ‘87. I remember from that time, I’ve never left, ever.

Ricardo Viviani:

So at that point they probably gave you many classes, with classical ballet as well as modern.

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, we had the modern, and one point the director – we called him, everybody called him El Negro Ledezma; that was his nickname – El Negro said to me, ‘yes it’s OK you’re doing modern, but you need also to get some of the basic, the real basic technique, so you must go to Lidija Franklin.’ She was the lady who was directing the ballet school, that was working with the company and school of José Ledezma, together as an institution. And he said, ‘You must go to her and start to take ballet classes.’ I was not so happy because I was afraid of the costume, but I went there.

Chapter 1.5

BalletRicardo Viviani:

Do you remember what kind of ballet that was? At that point you probably didn’t know, but looking back do you know what kind of ballet technique it was there?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes it was coming more from the Russian line of ballet, probably more from Vaganova.

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

We had some people coming from the States, most of them had connections with the Cunningham technique, but that was the technique that the school was teaching, basically. So we had some teachers that came and tought Cunningham.

Ricardo Viviani:

And did you have performance opportunities there where you could be on stage and gather experience as a performer?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, I started with El Negro, and then very quickly I think, in Venezuela, in the dance world, there was a lot of things happening in dance, at least at that time. I don’t know how the scene is right now. But I remember at that time there was a lot of different realities and different things. So there was also a group called Danza Hoy. It was quite an important group in the area, and they also had a school, and I decided to visit their school. Another place was the Instituto Superior de la Danza, and they also had classes in different styles. In Danza Hoy for instance they come from the Graham tradition, so I was taking Graham classes, and in the Instituto I was also taking improvisation and floor work, and Límon. Very quickly – because part of the reality, also in many other places, is there are many girls but not so many boys, and we have the chance if you're a boy and you are constant, you stay, you are present there – very quickly I had the possibility to work, to start to work, quickly, and experiences like participating in pieces that were put on stage. After two years dancing I started already to dance on stage.

Chapter 2.1

Connections to Kurt Jooss’ legacyRicardo Viviani:

There’s also a connection already to Germany with those people, can you tell us what that connection was, with Mr. Jooss?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

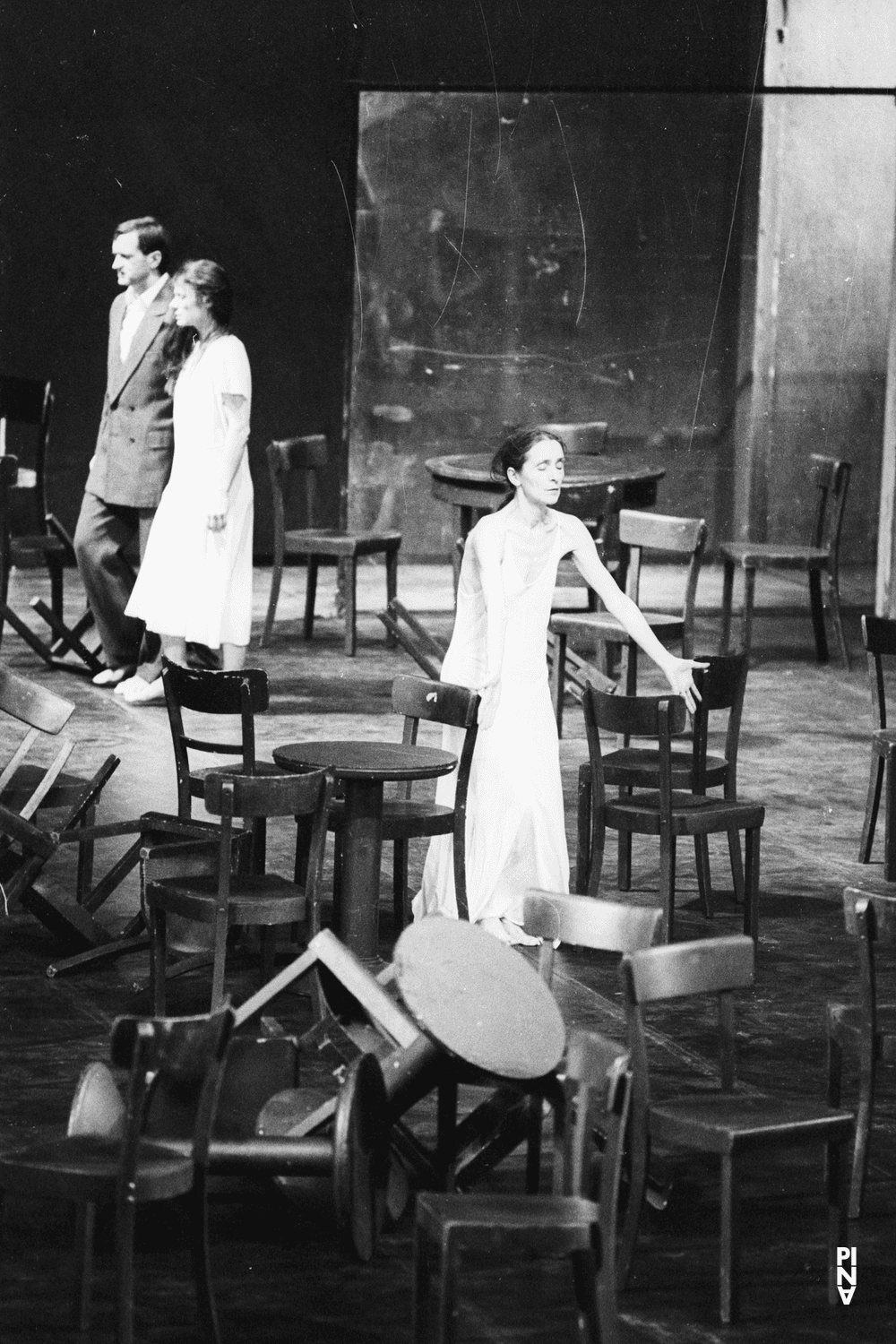

At the time I met a choreographer who was very influenced by his work, by the work of Pina, a choreographer named Luis Viana. I had the possibility to work with him in class, and after I was part of some of his performances, and from there I got the information of what was going on here in Germany. And the first video I saw, with some friends, was a video from Pina Bausch. I didn’t know who Pina Bausch was. We saw The Rite of Spring that night. It was a big shock to see that piece on video. And after – we were a small group of dancers – we were talking about our impressions. I could never imagine that one day I would be part of that. That was the first contact. Then some time later I saw Café Müller. It was not on television. Somebody had a video, and he brought the video, so there was just this person who had the video and me watching. I remember so strongly, I was crying after seeing the piece. It was so strong, the impression. There was something very sad about what I was looking at. What was the question? (laughs)

Chapter 2.2

From Jooss BalletsRicardo Viviani:

The people that were already connected with Mr. Jooss or Pina.

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

I was talking about this choreographer because he is somebody that introduced me to something that I didn’t know before. I didn’t know Pina Bausch. I didn’t know the work that was happening here in Germany and that was my first contact. I was sensitized to something that I didn’t know before. Then I met some people that I consider to be very important in my life, also for my later development as a dancer. I met Carlos Orta, who was at that time already in the States, working with the Limón Company, but he had his own company in Venezuela, Coreoarte. I met him in Venezuela, and I took classes with him. From his work – he was very influenced by Limón of course because of his work with the Lion Company. For me it was a new discovery, another aspect of dance, and I was very enthusiastic about the way he approached movement. I knew, after talking to him, that he was with Pina at the beginning of the company, and he talked about the school. He was a kind of mentor for me. He was trying to stimulate me, like, ‘Maybe you can go and do the experience, go to the school.’ Somehow, that started to work in my head. Also in the dance School, Escuela de Danza Caracas: Lidija Franklin, she was from Lithuania. She moved to Germany and worked with Ballett Jooss. At that time she met Alfredo Corvino, and she knew Züllig, Jean Cébron. When the Ballett Jooss did this big tour during the wartime, she ended in New York, and married a Venezuelan Diplomat. Then she came to Venezuela and started the school. So she knew it from the school, dancing with the Ballett Jooss. We had some conversations about her experience here in Germany. I was her student and somehow those talks with her were also very inspiring, the way she was talking about the school. And I was looking also for development and new possibilities. With her I also started to dream that maybe one day it would be possible to come and see the school.

Chapter 3.1

Completed University degree in journalismRicardo Viviani:

The study of journalism stayed behind you at that point?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Not really. I was doing it at the same time. I started to dance – I’d already started journalism – and then it was a very crazy time in my life because I had almost no time to sleep. I also did other jobs to survive, to make money, and I was going to the dance classes, in different schools, and I started journalism, so practically no time to sleep. But somehow the wish was very strong not to drop the dance on one side, because there was this passion there, or the journalism – I liked it, but in Venezuela it’s another kind of reality. We always say when you’re dancing – especially when you’re a boy and you’re 19, everybody, and me, I also believed – that’s a hobby. I didn’t have any pretension to become a dancer or to make that the way I can live; we’ll always talk about: What’s your profession? What’s your hobby? And dance was always considered in my country, at that time, as a hobby. I said ‘OK, that’s your hobby, but what are you doing as a profession?’ So I thought I needed to finish that, to be able to work in something, then be able to practice my hobby. Only a hobby. So I decided to keep studying until the end, and I knew it was a difficult time, but everything took its place by itself. Dance was taking more and more space, and I was giving less and less space to the study of journalism. But everything I needed to do for the university I always related to dance. We have different specializations; you can do writing or publicity, or audio-visual, media, television, radio, and so on. So I needed to do a lot of work, radio work, and television. Any time I had to work on something I made something about dance. Do you know what I mean?

Chapter 3.2

Life methodsRicardo Viviani:

I actually wanted to ask you the other way around. Now, today, in retrospect, especially with the systematic work with Pina, do you see any connection with being systematic in journalism, looking into things or working on certain aspects, research, do you think that influenced you or helped you in a way?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, in a way. I think already I had some kind of structure in myself. But I think the studies somehow helped me in that I found a methodology, somehow, to work. I believe, I continued to apply all of the knowledge I got there, if we’re talking about methodology, to the work that I developed later, definitely.

Chapter 3.3

Carlos Orta and FolkwangRicardo Viviani:

We’ll talk about that a little later. At this point you were talking to Carlos Orta, and learning about Folkwang – I believe it was a Hochschule [college] at the point that you applied. How was that, how was the application, the process of getting into it? How did that happen?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

I was in Venezuela, dancing quite a lot, taking classes, already giving classes, and everything happened very quick. Still it is a small country, and at one point I had the feeling that I’d done all that I could do there. I started to teach a little bit, and it was all a bit too early. I had the feeling that I needed to learn more. I was hungry for where I could get more information, I started to get nervous – in a good way. I was waiting till my journalism course was finished, and then once it was finished, that year I started to look for possibilities. I was trained in the school with Cunningham technique; my teacher El Negro wanted me to go to New York, and I said, ‘No, I don't think I want to go to New York.’ I had this idea in my head from what I saw from videos, what I talked to Carlos about, with Lidija, and with Luis, that maybe there was something else that I would like to try. Anyway I went to NY, I saw classes there, I spent some time there in my journey. I had planned a trip to New York, then going to Germany, then going to London. The second stop was here in Germany, and then I came and did the audition at the school. Then the next stop was London, but I really liked it there. I did the audition at the school, and I don’t remember why, maybe there was not much money any more to continue the trip to London, but I was quite satisfied with the experience at the school. I was very happy. I went back to Venezuela, then a couple of months later, they sent a letter that I was accepted into the school and I could come.

Chapter 4.1

New discoveriesRicardo Viviani:

How different was that from what you had already seen, learned? What new things did you learn, did you experience?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Right from the beginning I was very happy at the school. I had a great time at the school. It was another approach completely from the work that I was doing before. I got the possibility somehow to experience something I had the feeling I wanted to experience before but I couldn’t. It was something about being abstract; we worked a lot with the company in Venezuela with this abstract approach to the technique and the choreography, and everything was very abstract, also the influence we got from him, the work that he did studying Cunningham technique, but everything was very abstract. For me to come to Folkwang was a big revolution. I could be emotional, like a person; I don’t need to be abstract anymore. It was quite impressive. The human part, I see that you can translate that into the everyday work, like it is a person moving; it is a person. The awareness that the everyday work had something to do with the fact that it’s you and there is a space for emotions. It’s very complicated to explain; it’s not coming there with some kind of emotion, but the emotion is part of the work. I don’t know if I explained right.

Chapter 4.2

Hans Züllig and Jean CébronRicardo Viviani:

At that time there was still Hans Züllig and Jean Cébron. How were their classes for people that never experienced dance [in that way]? Can you describe a little what they were teaching there?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

For me, like I said before it was a new discovery, a new world, a lot of things to learn – how to approach movement. It took me some time to translate that, to have a feeling that it became mine, somehow, like it was in my body. When I did the audition at the school Pina was there. She was director of the school at that time. She was in my audition, and I presented a little solo, part of a solo by a choreographer that I worked in Venezuela with. He introduced me to the videos of Pina: Luis Viana. I had this little solo and we talked about it, the day after the auditions, but I couldn’t speak any German, I couldn’t speak any English. I saw Pina, just by chance in the stairs of the school, and she talked to me. Somehow she spoke English. I didn’t speak any English at that time, but I understood what she said, and I remember she said, ‘Good,’ and I got the idea that would be good for me to work with Jean Cébron, to take that little solo and to work on it with him. I said, ‘yes great.’ So I don’t know. I wasn’t speaking English but I understood. Right from the beginning I started to work with Jean; Jean was my teacher. I came into the second year and he was my teacher. And we started to work on that solo; we took that piece I brought to the audition as material, not as a piece, but as material, something that I knew already. And we started to work from different angles with that piece. I asked the choreographer in Venezuela if he was good with it and he was very happy that Cébron could work with the piece. So we used it as a material because I knew it and he started to give indications, and I started to understand the work with him, through a piece that I did already. I was very open because it was a piece done onstage, but I was happy to have the possibility to look from different angles. That was our first contact; we worked on that piece. That was the beginning of my work with the master. I worked with him for many years. I was taking his class. Of course I was doing the regular programme in the school normally, but I started to work intensely with Jean because I did the second year and at one point, he invited me to come to all of the classes, and then when I was in the first year I was also doing the second year, to get the most information as possible. At one point I was also helping a little bit in the classes, for the people that didn’t have so much experience, because I knew maybe a little bit more because I was in another year – helping a little bit to show the movement. That was a moment when Jean was not showing so much and he was asking other people to show and help in the class, and we also had the possibility sometimes to go to workshops with him in other places outside the school and help him showing the material. That was the beginning with Jean.

Chapter 4.3

Cébron RepertoireRicardo Viviani:

Did you eventually learn any of his pieces? Which ones?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

We worked one year on one piece. It was Model for a Mobile. I mean, during the classes we had space to learn different pieces. We learned a little bit of the horse (Wild Horse), parts of duos, things like that. But then he chose that piece. He was the only one that ever did that piece; he had forgotten it himself. It was somewhere, and he wanted to reconstruct the piece, so we worked on the reconstruction. We worked together for one year then we presented in the Schülerabend.

Chapter 5.1

Folkwang and the TanztheaterRicardo Viviani:

Fascinating. So there was already contact with the company here, probably. Did you come to Wuppertal to see pieces, go to dress rehearsals? Was that already happening in the [school]?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

But before that, the first thing was... Of course I knew about the company, but it was a shock experience because I came and two days after I arrived – the whole thing: coming to Germany, moving here, starting the school. It was a big impact. I was in the school. I had just started… And I remember Lutz – he was a teacher at the school also –, he said to me two days after: ‘Tomorrow you don’t come to class, you go and do the experience of having an audition in Wuppertal.‘ I didn’t know there was an audition, but Lutz sent me there, to get the experience. He was right because it is a great experience to do an audition with the company. So that was my first contact with the company. I came to Wuppertal and had this all day audition, learning a lot of material from different pieces. It was a big shock. So that was the first contact, first time being with Pina in the Lichtburg. It was great, she knew there was a little group of people that came from the school. At the end we talked and she mentioned that, ‘I know that you are in the school and we will be in touch.’ And the next time we met again was when some of the students were invited to learn The Rite of Spring. It was the revival of Rite of Spring and we took one month to bring the piece back. Before that was a couple of years when the piece was not played. I think that was 1992 [1 April 1993] if I remember well. There was a gap in between, so we spent a month rehearsing, morning and evening. But I was studying in the school, had a full day activity.

Chapter 5.2

German experienceRicardo Viviani:

And living in Germany, making the transition… Did Pina Bausch come at all at this time to give master classes or anything like that?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

At the school, no. She was there for the audition, and then she came sometimes for some exams, for the end performance, the Schülerabend; one day she came to see the Schülerabend.

Chapter 5.3

Performing as a guestRicardo Viviani:

Being in Sacre with the company, did you travel before you were [permanently] in the company?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, I think we went to Portugal, and to Israel.

Chapter 5.4

Staying with Folkwang TanzstudioRicardo Viviani:

There’s usually also this, ‘going into the FTS or not.’ At one point you were asked to come to the company; how did that happen? Did you audition again?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

No, I didn’t do the audition again. I learned Sacre, and I performed Sacre with the company. I continued in the school, and then when I was at the fourth year Pina called me one day to Wuppertal and she wanted to talk to me. I was quite nervous. I remember it was just me in the Lichtburg with her, and after the rehearsal she took me to the room in the back and she asked if I was doing something in my spring break. We had a month off, after the first semester. We had two semester in the year; after the first part you have a month’s holiday, then the second part of the year starts. She asked me if I was doing something in that time. I said, ‘No, I’m not planning anything.’ She asked me simply if I would be interested in learning the role of Pylades, in Iphigenia. And I thought: ‘What?‘ I thought I didn’t understand right what she was saying. ‘Of course I want to!’ I was super happy that she came to that idea. I never understood it really. Oh wow! I had this month working with Ed, here in Wuppertal, sometimes in Essen, learning that part. It was fantastic!

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

I just learned. She didn’t say anything. Just said to learn. There’s so much of Pina’s way of moving, and quality, it was incredible; everything is there in this role. It was a beautiful experience. And then at the end of that experience – I think she never saw me do it or anything; it was just for learning – I remember she was asking what I was planning. ‘What are your plans? What are you planning to do after the four years are finished?’ I didn’t know exactly what to say because I knew that Jean Cébron had this idea I should do the extra year with him, a fifth year, the master. Afterwards when it was clear, I came to her and said ‘I have this offer from Jean.’ It was something I was very interested in, to go deeper into the work. I knew that for that year, Jean said, we just spend a year just with him. I was concentrated just on working with his approach to movement, dance, whatever. It was a year where we also worked on Mobile. And then I said to Pina, ‘I have this idea to work with Jean for one more year.’ And she said, ‘Ah, that’s good.’ She was happy that it was happening with Jean. Jean was her teacher, too. So I was very happy also.

Chapter 6.2

Connection points between these artistsRicardo Viviani:

Since you had a very intense connection with Jean, and a long time working with Pina, I’d like to talk a little more about Jean. You said he was also her teacher, or they were partners at some point – she was doing his pieces. How deep is the connection? How do you see this connection between the two of them, the qualities? Was there an interplay there, that she learned from Jean, they developed together? How do you see the connection between those two artists?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

I think it’s a very important point in the history because he was carrying a lot of things I presume he also learned from the time before in Folkwang, that luggage; he carried that. He was there; he was like, ‘you take that.’ (gestures) He was the person who was in charge of that tradition, of continuing, or call it the technique, or the way that we learned in the school. And of course Pina also had this experience. She also worked with Jean, in his classes, on his pieces. Little by little I started to understand, because it wasn’t easy to work with Jean, in the sense that he always said that young people want everything very quick, the results now. He was talking about how things need time. At the beginning I really didn’t get it, what he wanted, because sometimes his classes were very long, sometimes we wanted more excitement, like it should be quick. I understood many years later that this information that he gives, sometimes it was information that didn’t work at the moment, but it was information that I didn’t forget, and somehow was in the body, but it was like a seed, it was there, like putting seeds. And at one point when the conditions were there, something started to grow and I started to recognize things that I couldn’t see that Pina was talking about when we were in a process, or working on a piece, or working on a repertoire piece, and sometimes very practical things, talking really about some movement qualities, energy. And I could make the connections, something that I was already in contact with – this information – through Jean. And this was not something I was in connection with in Venezuela. I knew that Jean was the source. More and more I was making those connections, and very often Pina talked about Jean. It was a period when he was teaching here in the company and she was encouraging people to come to the class, saying how important it is to come to his class. It was a very special class. It was very complex. Sometimes it was more about the understanding of something that is just moving. There was also a lot of movement and moving, but it was not only about that. There was also the possibility to take time to understand something that would not come just right now. Pina was always talking about Jean. I knew that there were a lot of things that had been discussed between them, and he'd continue to talk. As I said, at the beginning, when I came to the school it was great that she said I should take that piece I was bringing from Venezuela and work with Jean. It was funny because it was a very dramatic piece, a lot of drama, and I knew some time after that Pina and Jean spoke about me and Jean said to Pina, ‘He’s a clown.’ (laughs) He didn’t know me, but that piece was a drama piece, more in the register of something dramatic. But he said that time to Pina, ‘He’s a clown.’ It was very funny because many years later when I came to the company, we had a little talk to Pina about that. Because in that drama he saw something funny about me. And it’s funny because afterwards, in many pieces by Pina I know I had the chance to [be funny]. Because I like to make fun. When people enjoy having fun... I became a little bit the clown. Somehow Pina also used this part of me.

Chapter 6.3

Growing the knowledgeRicardo Viviani:

Going on chronologically, there was this one year working with Jean, then after this year what happened?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

That was the moment of transition. I knew that Pina wanted to know what I was doing. Of course when somebody asks what you’re doing, you suppose that probably she would be interested. I guessed so. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. At that point I was also working with Susanne Linke in the school; we did a piece. Susa was starting the company in Bremen. It was a fantastic time with Susa. I liked working with her very much, and Susa was interested if I could come to Bremen. I talked to Jean and I said, ‘I have this situation. Pina is asking what I want to do next year.’ And I was floating with these possibilities. We had a couple of talks. Probably logically, Jean was recommending I go to Susa and have the experience, see if I like it, because he was thinking if I go to Pina, I will stay for a long time. That’s normal, to stay long. I thought, ‘So if you go to Susa, you will have the experience. Probably you can go later to Pina.’ At the end I think I followed what my heart said, and I was ready to invest time here, so I came to Wuppertal. That was ‘95.

Chapter 7.1

Learning repertoireRicardo Viviani:

So learning a lot of repertoire first: that year there was Sacre, we already knew, Todsünden [Deadly Sins], Kontakthof, 1980, Nelken, Viktor, Palermo. There was also Das Stück mit dem Schiff [The piece with the ship] that year, Danzon and Nur du. Did you do all of those pieces?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, right from the beginning I was in every piece. I remember the company was on tour, could be they were in Argentina? We were a big group of new people in the company: Michael Whaites, Stephan Brinkmann, Eddie Martinez, Chrystel Guillebeaud – Andrey was six months before me, but he was also in that group –, me… It was a bunch of new people in the company. So, while the company was on tour, we were here learning a lot of material, looking at videos, learning with Ed, with Beatrice, with different people, learning pieces, watching videos, making notes. That was a very intense preparation process. Of course, at the beginning we started to play those pieces, and in many of those pieces sometimes I was participating, not doing so much, maybe small parts, sometimes a little bit more, then starting to develop different parts in the pieces. But already from the beginning I was almost in every piece.

Chapter 7.2

First new pieceRicardo Viviani:

And the first creation with the company was the co-production in North America: Rena Shagan, different places. That was a new process for you. You had been at Folkwang, but there was some difference in the way Pina worked. How was that, coming to that task-oriented [enviroment], going into co-production? How was this experience?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

It was very intense, but at the same time I felt really relaxed. Already from the beginning I had this feeling with Pina that I can trust her: a kind of trust. I was feeling I can open myself and I had a feeling I was moving in a safe space. It was just trust. It’s very rare feeling that, because I know that there was a kind of opening, because you are giving something, from myself to somebody that is so important in the world, a big name. At the same time I felt free in that space. I was protected. I didn’t have pressure. There was always a big respect and admiration for Pina, but from the beginning I had the feeling I could be anything, I could be stupid, I could be open, I could be serious, and I always had the feeling she was just observing, she was not judging. And that was a great feeling, because this feeling, with the years, got stronger. We didn’t talk so much, as I guess you know. She didn’t talk so much during the process, during the pieces, but during the years I always had the feeling I had more and more space. And she created, somehow, the freedom that I could go a little bit in other corners where I was not before, trying to look for little things. I had a feeling she recognized that. And when somebody recognises that, you say, ‘oh she saw it.’ And then you try look [further]. It’s like you are looking for something, you bring it, ‘Look what I found,’ and she looks at it, and she appreciates it. Then you go and look again in another corner, you understand what I mean? And that was part of my process. It was an inspiration also for why I continued over the years. I think I was also bringing a lot of things from different corners. I had the feeling we had this communication; she was interested in what I was trying to look for and I had the feeling I had the space to bring all those things. Already from the beginning of the first piece – having been in the school you already have this kind of experience, working with teachers that worked with Pina, that influenced her, then working with Jean. Because we did it also, a little different, but we did improvisation work. It was an experience that allowed me to feel more comfortable when I came to Pina. I don’t know how it would have been if I’d come from another experience, like come directly from Venezuela to work with her. I had the experience already in the school, and it was a good school for that.

Chapter 7.3

How was your personal journey?Ricardo Viviani:

You say that you found space there, and you were always getting more space. If I look you’ve been in nearly every production that was created since that year. As you see your process within that – I know you already said that you were always looking for things – do you see a development there? Could you go deeper? It’s a little too much, because there is a depth, but maybe a growth? Did you grow into that, that’s the question?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

[From] when I started in the company to what we did last there is a journey. Many things happened in that time. I thought also that it is very important that we have the time, that I have the time to grow, to develop something. That was very important. Again, somehow I go back to Jean. He said, ‘Things they will come. It’s like a little plant, a little flower. If you have a flower and you want this flower to be open and beautiful, you cannot force it. You just need to wait for the flower to come by itself. You cannot force it.’ And Pina said many times, ‘My dancers are like flowers and we have different kinds of flowers. There are flowers that go one day, and then maybe they disappear, there are other flowers that need more time to bloom.’ And that’s a beautiful picture, not just a picture, it’s a motto for life. I knew sometimes there were things that I couldn’t do, for different reasons. I would like to do that, or that, but I couldn’t do it. This process I was not trying to force. I knew that sometimes I dreamt something – I can’t explain – but I knew that it was not now; it was somewhere. Then many years [later] something would come that I thought about years before, and maybe that would come into a form where she feels what I’m trying to say, and then it would be in the piece. That’s for me what I can call growing or development. There was space, and the time, to let things happen. It’s a process, because you are working every day. You wait. You’re working on what is possible right now. It was great that somebody like that also had the vision that they take you as you are here, and how you are in ten years. It’s actually fantastic.

Chapter 7.4

Iphigenie auf TaurisFernando Suels Mendoza:

Always a very special thing for me in my Tanztheater Wuppertal life. In those years after my entrance in the company, from time to time, Iphigenia came back. Dominique and Bernd were doing the piece. I became the understudy for Bernd, Ersatz [replacement] if something happened with him. And every time Pina was with me very clear: ‘Are you rehearsing? Do you know the part?’ She’d always ask. Sometimes I rehearsed when they were rehearsing, behind them, and she saw me. Sometimes she made little corrections. But somehow I wondered if that would happen, that I would be dancing that piece. From the moment I learned it to the moment that it did happen was 15 years, and that’s quite a long time. For me it was just a pleasure to go into the studio and do those movements, because they are really beautiful, pure Pina movements – the intentions, the quality – and during the years it was a process; you can make things better. And then I worked also with Bernd because he was doing the role for many years – I got all the points of view of the part – until the day that it happened. Now it was the moment to do it. After so many years, it was a big responsibility, but at the same time I thought: ‘It’s right.’ It was the right moment to go into it.

Chapter 8.1

Learning Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

That one piece you saw on video in Caracas, many years before even thinking about coming here. It’s a crazy question in this universe, but when did you start learning it?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Quite early when I came into the company, Pina asked me to look at Dominique’s part for Café Müller, so it was quite early, right after I came into the company. So I started to come into rehearsals and look with a different eye. I was just looking. It was nothing about – it’s a very particular piece because Pina was inside, and also the atmosphere of the rehearsals and the place was quite intimate, even for somebody who’s not in the piece, but is trying to learn, so how do you find space in a situation like that? It was not easy; I am not part of it, but I need to do what they ask me to do, to look. It was looking, but without looking; being there without being there, because you can disturb this kind of atmosphere. It was completely different from being in other rehearsals of the company – also because of what the piece is talking about and what the feelings are like. I did also Danzón. I learned it and I was in the rehearsals before I did it. But the atmosphere, from what the piece is talking about, is completely different. Café Müller and Danzón: Pina is in both of them. This is why I made the comparison. That was my first approach, then I started to look at videos. I looked at a lot of videos, but concentrated of course on the Dominique parts. I saw so many videos until I thought, ‘Now I have the information.’ I never really learned the movements as movements. I think I just experienced the feeling of the piece.

Chapter 8.2

Learn by quietly watchingRicardo Viviani:

I have to clarify that. That means that you didn’t even get up and do the glissade from Dominique into the floor?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

No, no, no. (laughs) I was just there, she said, ‘Look, look at Dominique.’ And I was looking at Dominique, and tried to get what I could get, being in the rehearsals and looking at the videos, but I never even thought to try a movement. I think it was not about that, but I had the experience to look as if eventually one day it could happen that I needed to be in the other part – so far. But that never happened. And I was doing Sacre, so I never really saw the show because we have the warming up for Sacre during the rehearsal [performance]; they have also different time of rehearsals. So I was missing a lot of rehearsals for Café Müller, but I thought it was ok because I’d concentrate on Café Müller. Until the moment that we were in Brazil. For personal reasons Jorge, who was the understudy for Jean Sasportes in Brazil, was not there, and there was a situation that Jean got hurt, his back. He couldn’t move. The day of the dress rehearsals he came down to the breakfast and said I think I cannot dance tonight. Jorge was not there, so they had a little meeting to decide who can do the part and they called me to start to work during the break, to do the dress rehearsal in the night and I did the four or three shows that we had in São Paulo. So I learned the same day, and I danced it that night. I couldn’t learn everything so quickly, because it’s quite a complicated part. In a way it’s very open, but at the same time not. It’s tricky, but I knew Jean was with me, even with his back pain, he was behind the stage telling me what I should do, from where I should come in. He’d say, ‘Move that chair, look at that here.’ He was giving me indications, so I was going on the stage, then coming back and he was waiting for me at another place. That was my week in Brazil. At the same time I was doing Sacre.

Chapter 8.3

Casting questionRicardo Viviani:

Did you start alternating [the role] with Jean Laurent?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

No, that was in Brazil; he couldn’t do the show. I did the show, and the dress rehearsal. I was just working with him behind the stage. Then we went back to normal Café Müller. He did it for another couple of years, until the point, I thought, they decided he was not doing it anymore, they started to think of a new cast, and I came into the piece.

It’s funny because normally when you are learning a role, you know that you are learning. Then you have the time to look at the videos, to prepare yourself, to get all the information, then little by little you get into the piece. But with Café Müller it’s funny because I did it like a shock: you have the dress rehearsal in the night; I was doing Sacre, super tired, of course because Sacre pulls you into a special state of body and mind. I knew I had to do Café Müller tonight, and I had just a break to learn what to do in the performance. Sometimes in this kind of emergency situation a lot of things happen that are right. And it was an emergency situation. I did Café Müller and it was a big shock, but after it happened, some years, they decided I should do Café Müller for Jean, so I started again from the beginning, looking at the videos, getting the information. It was crazy because it was so much information that I didn’t know before, but I did the show. It was a new experience.

Chapter 8.4

Carefully revisit the roleRicardo Viviani:

The first time that you did it, was this quick [learning process], then you went back and started learning again. And you say there was new information that you didn't have before. Can you maybe say precisely what kind of information that was? That was being added.

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Of course when I started to learn the piece to perform it again, I went through a lot of videos. I started to look at the videos with Rolf, then I started to look at videos with Jean, in different years, and of course I started to see the different approaches to the work: what it is to move the chairs, how Rolf took care of that and how Sasportes did that and how I did that, because I also did it and had the experience already; it was something already registered in the body, from what I did. I knew I had to do the performance and had this time, and I needed to have this information. And there are a lot of different approaches. There are things that belong to the role, but you also see differences in how they approach it. And it is something that we spoke about during the process, because Malou and Dominique were in the piece originally, and also with Rolf, and afterwards with Jean. There are a lot of technical things, when to be slow, when to be quiet, when to be excited, when to run, when to take care that the chair won’t fall into the audience. Already in the video you see that Rolf is coming from the right, then Jean is coming from the left. In which moment has that changed? So I got a lot of information with Jean; of course he did it even longer than Rolf did. He had more experience, in time, more performances; there are more videos to watch than Rolf. So that was the work: how can I integrate, because there are so many sources; there are the videos, [there is] what I found in the book, what is written, what I saw from Rolf, what I saw from Jean, what Jean told me, what I experienced before and what Dominique and Malou said. These are the different things. And at the end you need to be on the stage. How can you use this information to deliver what you need to deliver on the night. It is a complex part, also between the people on stage, there’s a lot of negotiation. When they did the piece at first, or before, everything was more unorganized. Of course, many things started to be more codified with time. I think it’s normal, and happened in many pieces. It happened to me. When I did it the first time in Brazil, I was not organized, but it happened. And then many years after, I was in the same situation, but I already had all of the tools to deal with the material. It’s a lot of negotiation with all the people who are on the stage because of the characters and all of the chairs, and you are the one moving the chairs, so the other actors have different actions and approaches to the chairs. When you change the person who changes the chairs, the chairs are changing, so you need to be in contact with the other people to see, where are the needs? And then I say, ‘Ah but I saw that and he did it like that, and she told me that’ It’s a lot of… You need to be very open, and negotiate all that information, to make that universe work.

Chapter 8.5

Where did that boy Fernando fit now?Ricardo Viviani:

And within all of that complexity, do you remember that boy that saw Café Müller when he was 19 in Caracas, and now does that still move you in that way?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, I think so. I remember in Brazil, when I needed to do it, there was something so strong, that had nothing to do with me as a dancer, or what I needed to do that night, moving the chairs; it was something more about a place, a kind of sacred place, where Pina was involved. And because of the fact she was not there anymore, and I was entering that space, I didn’t think it was the right space for me to be. It was very funny, I felt like a stranger, and I knew I had to do that because it was a practical thing. Jean was sick, I needed to replace him. But already to enter this place, the energy that the piece creates, being now inside, is so strong – because I had the experience before, when I was learning for Dominique; I felt that strong energy and how that space is private, intimate. It was difficult to be there, even as the understudy; it was also difficult to be there, even though that is your role. At the moment it was difficult to be there. And it was difficult to enter this space in such short time, and I think that memory of the strength of the piece came very strong in that moment. It is a space that I have a lot of respect for. Something about that (gestures) intimate space. The space itself has its own force. Being around that space is already strong.

Chapter 8.6

ChairsRicardo Viviani:

Fact checking. I take it that by the time you came into the piece, there was already a set number of chairs. There was no variation. Is that correct?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes and No. We can have another complete interview if we talk about chair numbers. I mean, it is a conversation point because before there were much less chairs than after. Then at one point the number of chairs changed. What I understood was, Pina wanted more chairs, but it had also to do with different stages; sometimes when the set is different, when it’s not the glass version, when it’s the other version, the number of chairs also changes. There is not a precise number of chairs that need to be on stage. I just have references, and then, because maybe I am a little bit precise, I start to work with numbers, how many chairs we have here, and count them in little pictures. And I tried to find the middle, where I can have... One time I mentioned the number of chairs, and somebody said, ‘We never count the chairs.’ There is no information on how many chairs are going to be on stage; you need to negotiate that. I got that information from the picture, but maybe it is not a good idea to mention it right now. Because in the end, you are responsible for the chairs. Jean took care of how he placed the chairs onstage. From my experience, Rolf didn’t do it. It was more free, in a way. And it got, with time, more codified. There is some kind of order. So Jean was the one who knew it, how he organized the chairs. If you need to negotiate with somebody, because somebody has a special need at one moment, it is good to negotiate with that person how to deal with this situation. But they don’t need to know how you work with the chairs because that is my business. I am the one who is taking the chairs apart. So now I know more or less, and if somebody says less chairs, then we put less chairs, because we also have rehearsal directors; they look from outside of course, and they have the feeling there are too many chair, so we will take some chairs out. Then I need to reorganize myself, because I am organized and I know, ‘Ok I have…’ And I also do pictures from the different performances. I have it in my notes. I know what I did here, what I did there. After, when they come and say, ‘Oh here is something missing,’ before they do that – because I always have a look with Dominique, with Bénédicte, before the show, to see if it looks natural, and there are enough chairs, there are no holes; maybe one chair doesn’t look so good and we change it. So we change the chairs. But before all that I spend one and a half hours working on the constellation, how I place those chairs, so they look the way they should be. It is not like the technician puts out the chairs and that’s it. I don’t know how it was before. But in the different videos, really in the beginning they were very different, the chairs, from one performance to the other. Afterwards, with Jean, you can see there is more or less the same constellation – in the same series of performances in one place. So. (laughs)

Chapter 8.7

Being Rolf BorzikRicardo Viviani:

Very good. In a sense you became Rolf here, the set designer.

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

I mean I really started to enjoy the moment when I am alone on the stage, because I arrive most of the time before the dancers. It’s like my little ritual. I start to move with the chairs, and already imagine what will happen, what are the needs of the piece. And it is actually very beautiful. At the beginning that made me really nervous because I was thinking, ‘Oh I can hurt somebody. It’s not the right thing.’ But afterwards I started to drop those things. So now when I go into the piece, I just enjoy creating those paths between the chairs. It’s actually fun.

Chapter 8.8

Special performance spacesRicardo Viviani:

Unusual set-ups, such as plexiglass and live music: can you tell me about some of your experiences, how that influences, how does that affect the piece?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

I think I did it once. That was in Nîmes. It was the only time I did it with live music. It’s beautiful. Also with Sacre, because it is a feeling that… When we have the music on tape, it is beautiful music, but once it’s live you hear the music differently because there are other things. And certainly the music becomes like another person onstage because it goes everywhere. Sometimes you hear things that you never heard properly on the tape. Then it is going in different directions. So we have this interaction with the music, that’s completely new and that’s beautiful. I am looking forward to performing the piece now in November [2018] with live music again.

Chapter 8.9

Performing both piecesRicardo Viviani:

Two more things: one is performing Café and afterwards Sacre; it’s a change of pace, how is that for you?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Yes, before, when I was not doing Café Müller, I had class [training] while Café Müller was running, I never wanted to see Café Müller because I knew I needed to be in the warm-up. I didn’t want to miss the warm-up for Sacre, so I was preparing a lot for Sacre before. I thought that it was the right thing to do. I was very concentrated for Sacre. So I was a little bit nervous the moment I started to do Café Müller because I thought, ‘How are you going to deal with the fact that it’s two different physicalities?’ I needed to prepare myself differently to how I prepared myself for Café Müller because I needed to run, I needed the attack. For Sacre I needed more elasticity; I’m stretching more. And I practiced the piece – piece by piece from Sacre – before when they are doing Café Müller. And I was saying, ‘How am I going to do that? I know I am very used to those rituals.’ I knew I always did my preparation for Sacre in a special way and I was really... Funnily, I discovered it was easier, because I just rehearsed less, and I didn’t have the time to think so much. So I was preparing for Café Müller, quite well. I didn’t do anything for Sacre, and at the break I just only had time to change the costume I have from Café Müller, and put on [the Sacre costume], and I am sweating and I come sometimes onstage, and I didn’t do the ritual I did before, and I started to realize very quickly, it was better for me. Less thinking and something was more... I don’t know. It took me many years to drop that. I dropped it, and it was going well, actually. I thought it would not work, but that was probably in the head. It was even better. I was somehow more ready, even if it was the fact of being onstage, I don’t know. The way I moved there somehow made it easier to do Sacre.

Chapter 8.10

Chair falling in the Orchestra pitRicardo Viviani:

Before I ask you the very last question, sort of a standard thing: is there anything else from Café that I didn’t touch on that you would like, you think could be added at this point? We can always do more.

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Maybe an anecdote.

We always need to take care of where the end of the stage is. There is a lot of taking care of people; it is the role where you need to take care. I take care of the people so they don’t get hurt on the stage, make the space in a way they can do what they need to do. All those obstacles, but it’s a reality that we cannot hurt the people in the audience. It is a very complicated situation, because sometimes, what’s the priority here? Sometimes one chair takes the other one. I remember in Nîmes, we had live music and the instruments for Sacre were already there. Café Müller has a little orchestra, but for Sacre they have this big round Timpani. Once, in the dress rehearsal, one of the chairs fell onto the instrument. Such a big noise. It was a big shock.

And somebody said, ‘They have insurance.’ ‘OK they have insurance.’ They tried it afterwards and everything was ok. Nothing happened. The sound I still have in my head. It was from the chair.

Chapter 9.1

‘All part of one large construct’Ricardo Viviani:

What is Tanztheater [dance theatre]?

Fernando Suels Mendoza:

Maybe small and big. Pina said one time – maybe somebody was not very happy about what he was doing in the piece, or she was doing in the piece, because it was like that (gestures ‘small’) –, she said, ‘That’s what we are, sometimes just like that and sometimes like that (gestures ‘big’), and if I am not ready to accept that, we would not exist.’ Something like that. It is so important; that is super important, as important as that, and as that. (gestures ‘small’, ‘medium’ and ‘large’) It is not about, ‘I’m doing more,’ or, ‘I’m doing less.’ You see something in the work, it’s also very similar to that reflection towards someone who was not happy with what he was doing in the piece. We do tiny little movements, and they are as precious as when you do very big and virtuoso [moves].

Suggested

Legal notice

All contents of this website are protected by copyright. Any use without the prior written consent of the respective copyright holder is not permitted and may be subject to legal prosecution. Please use our contact form for usage requests.

If, despite extensive research, a copyright holder of the source material used here has not been identified and permission for publication has not been requested, please inform us in writing.