Interview with Ed Kortlandt, 23/5/2022

At the beginning of the Interview Ed Kortlandt talks about how he started dancing. When he was seven years old he saw a man and a woman dance the Polka and was fascinated by it. He continued to do Folk Dance as a hobby and later joined a new company in Amsterdam where they did Folk Dance professionally. He started taking ballet at 16 and continued to do it as a hobby during school and later during his studies. He then went on to study music and dance at the Amsterdam Conservatory.

| Interviewee | Ed Kortlandt |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Camera operator | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20220523_83_0001

Table of contents

Ed Kortlandt:

In the piece Nelken, I – like everyone else – tell a story about how I came to dance. I was seven years old when I saw a man and a woman polka dancing – it was like they were flying! That really moved me! My parents wanted to go on vacation without the kids, so my brother and I were sent to a camp for two weeks, in the woods with other teenagers. The camp master did folk dancing, he danced with his daughter and I thought it was wonderful! I wanted to do that too! So, I took folk dancing as a hobby for years. When I was sixteen, something new came up in Amsterdam: a new dance company was founded by people from the folk dancing scene. This company didn't paid, they had no money. They all had other jobs, but the goal was to make it professional. In the Netherlands, unlike in Germany where a theater has multiple stable companies, everything is separated: opera, concert music, plays - the theater is one thing and the company is another. With this group we did folk dancing here and there, like the ballet companies, we performed everywhere in the Netherlands. Our role model was the Moissejew Theater in Russia with Russian folklore, and also the Berjoska Ensemble, which is only made up of women. We had Russian, Yugoslavian, Scottish and Romanian and Bulgarian dances - a lot from the Balkans, a really varied program! I danced that with a lot of pleasure! Extra-curricular, at 16, I also started with ballet - because I wanted to do something different than the others. That also pleased me a lot, the physical aspect appealed to me very much. And so during school, and later during my studies I always had dance and ballet lessons as a hobby - and also music. I started with music very early on.

Chapter 1.2

Early years in AmsterdamEd Kortlandt:

I grew up in Amsterdam - that means, 20 years of freedom, the first love, school, and later university. After high school, I first studied medicine because I come from a family where dance as a profession was not an option. My mother was a doctor and my father was a professor at the university. That direction was set for me, but during the course of my studies, music and dance became increasingly important to me. I dropped out of medical school because I had to do military service. I was in the military for two years, even made a career there, I'm still a lieutenant, but I can't be drafted anymore with my 77 years. I was even offered to become a professional officer, but I wanted to dance! That didn't bother anyone in the army - one would expect to be looked at skeptically, but that was not the case at all! Everything was in order. After this time I started in the studio of Mascha ter Weeme - she was one of the founders of one of the largest ballet groups in the Netherlands, Ballett der Lage Landen, she was the director of it. She had a private ballet school. In addition I studied ballet at the Scapino Dance Academy, and at the same time I studied flute as a major, piano as a minor and the theoretical subjects at the Amsterdam Conservatory - so both: music and dance.

Ricardo Viviani:

Where did you learn ballet?

Chapter 1.3

Pina Bausch in RotterdamRicardo Viviani:

You eventually got a job at a Modern Dance Company in Rotterdam - how did that come about?

Ed Kortlandt:

I completed my music studies with an exam equivalent to today's Bachelor's degree. I stopped playing my main instrument and didn't finish my ballet training, instead I audittoned for a new, small modern dance company in Rotterdam. The director had studied with Martha Graham in New York and she gave modern dance lessons in her style. We also had ballet training, and we had guest choreographers: Pina Bausch was one of them. Ineke Sluiter, our director, had seen Pina Bausch in Cologne when she won the first prize in the choreographer competition and she asked her if she wanted to come as a guest to stage the piece with us. She agreed. It was called Im Wind der Zeit, and we learned it. Lucas Hoving, who also had contact with Pina and our director, also came as a guest choreographer and made a piece. It was a very interesting time: it was a very small group, but with well-known, top people!

Chapter 2.1

About Im Wind der ZeitRicardo Viviani:

And this modernity that Pina has brought to you: were you aware that it was going in a different direction and was something new? She had already received a prize for it - that was already an acknowledgment? Did it make an impression on you, could you identify with her work?

Ed Kortlandt:

The piece Im Wind der Zeit that Pina restaged with us was relatively traditional. There was music, and there was movement material derived from modern dance. You couldn't guess in which direction it would go later. It was an interesting time. I was in that company for three years. The problem was that there were also other choreographers, and these guest choreographers had ideas! With those ideas and with what they expected I thought: "well, as a hobby it was actually much nicer!" I could go two ways: either you follow your heart's desire - or you make it a profession, where you make money and do something else as a hobby. So I thought, that maybe the second model was better for me. So, I enrolled in dental medicine at the University of Utrecht - at that time, it was THE university for dentists. I had a place to study, everything was already settled: the end of career as a dancer. Then, I attended a summer course with my company in Cologne - almost as a conclusion to my career. Among the teachers were Hans van Manen and Mary Hinkson. Mary Hinkson came from the Martha Graham Dance Company and she was the director of it, because Martha was in the hospital, and she offered me a contract! You have to imagine that: a world-famous company, hundreds of dancers unemployed - and I want to quit! I thought, this is a gift from God! I can't just say: now I'm going to be a dentist! That threw all my plans overboard. They paid for my flight and the hotel - they wanted me so badly! Yes, my jaw dropped! I couldn't say anything but "Yes"! So off to America!

Chapter 2.2

In New YorkRicardo Viviani:

At the time, Martha Graham was already old, but she still worked for quite a long time, which one could not anticipate in those days. And in the meantime, Pina started her company in Wuppertal: did she make you an offer?

Ed Kortlandt:

No, wait a minute. Martha was certainly an extraordinary person! I can't stand up right now, but at a rehearsal there was a situation where a girl had to do something and fall back, and four men had to catch her and lift her up like that - and that didn't work out right. Then Martha came, all bent over, and did it, let herself fall! Nobody had expected that, they all got panicky - but did it and then she was up there like that! Then, they put her back down and she went back to her place. The director of the Amsterdam Conservatory, where I studied music, he had Parkinson's. When he gave a speech, he would put his hand in his pocket, so it wasn't so noticeable. He had been a wonderful pianist - I knew him well, I went to his house once, there were two Steinways side by side in one room and nothing else. He used to give concerts in the house, and when he sat down at the piano, he could still play! But when he stopped, he it started again. It was similar with Martha.

Chapter 2.3

Returning to EuropeEd Kortlandt:

I kept in touch with Pina, and when she wanted to start in Wuppertal, she wrote me a long letter, telling me that I should definitely come to Wuppertal! But it was too short-notice for me, and besides, I felt comfortable in New York. Coming from Amsterdam, where so many different people walk around and you're anonymous but still belong - it was the same in New York! It was like home. But working with Martha was such that you didn't get to see her that often. you worked with assistants, with videos of roles that other people had already created. So it was a bit museum-like. New York is breathtaking, but always the same somehow! I wanted to go back to Europe, where every 200 kilometers you enter a different country with different languages, different food, different people! This diversity! New York was a bit too limited if you only stayed in the dance and art world. So, first of all, I had a desire to go to Europe, secondly, Pina really wanted me, thirdly, my girlfriend Tjitske Broersma also came to Pina - and I wanted to give it another try! So then I went to Wuppertal!

Chapter 3.1

Tjitske Broersma in NachnullRicardo Viviani:

Before we talk about Wuppertal, Tjitske Broersma also learned another piece by Pina, Nachnull - did you see it back then?

Ed Kortlandt:

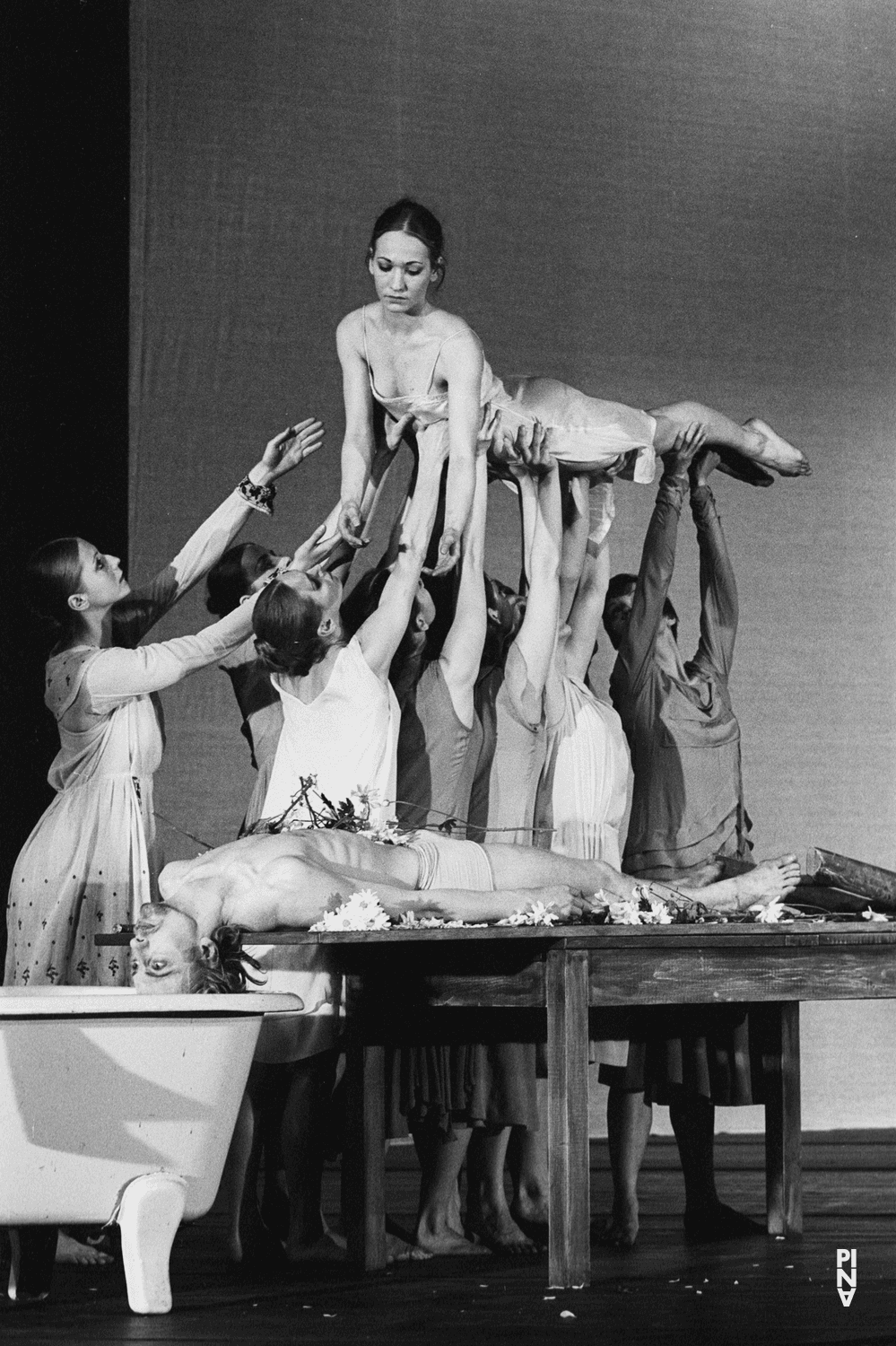

Yes. I saw Nachnull. The title refers to the zero hour, after the catastrophe. There was a movement where this arm - I can't do that anymore - goes from here to there! An interesting piece - also the piece Aktionen für Tänzer! Before her Wuppertal time, Pina had to make two test pieces. Mr. Arno Wüstenhöfer, the director, had discovered her. She came to Wuppertal and he gave her the task of making a choreography to a certain music, his house choreographer should also do it - so two choreographies were created to the same music! And that was the piece Aktionen für Tänzer that Pina made, which was wonderful! I saw it! And then there was Wagner's Tannhäuser, in the opera there is the Bacchanal at the beginning. Pina was asked to choreograph it, and she did it wonderfully! The ballet critic of the time, Horst Koegler from Cologne, saw it - that was in 1972, a year before the Tanztheater Wuppertal started - and he wrote: Yes, you can take the train from Cologne to see the beginning, and after the Bacchanal you can take the train back to Cologne! He never wrote such a review about Pina again because he was very conservative, in Pina's first pieces - Fritz, Iphigenie and Orpheus - he spoke of "kitchen stuffiness" and "bed sheets" and so on. But with Seven Deadly Sins and Songs, which had a lot of humor, he suddenly changed his mind and suddenly understood, and wrote positive articles about her! But he didn't have a good word to say about her first pieces. Pina meant that the man doesn't realise the damage he's doing.

Chapter 3.2

YvonneRicardo Viviani:

You came to Wuppertal and at first Pina still participated in some pieces herself. Yvonne, can you still remember that?

Ed Kortlandt:

At the very beginning with the company, Pina was asked to play the Burgundian Princess in Boris Blacher's opera Yvonne, a silent role. That was completely new for Pina - she hadn't even started in Wuppertal yet! That was very strange! The singers back then couldn't do much with the music either. It was all so (sings) and I think Pina had a good influence on those people who looked quite lost. Kurt Horres directed - wonderfully. I saw the performance twice. And there are two things: one is that Pina was even better the second time than the first! At the end she dies because she has a bone stuck in her throat - and how she did it, it gave me goosebumps! And the other thing is that Pina's later pieces always had some challenges for the dancers. In Sacre there was earth on the stage floor, in Blaubart it was leaves, then there was even water - all things that were quite hindering when dancing. That reminds me of Boris Blacher - there was a moment where marbles rolled across the stage, someone sang, "What are you doing?" and the other replied "I'm making it harder to walk!" - and that's exactly what happened in Pina's pieces: She made it harder to dance!

Chapter 3.3

First season and FritzRicardo Viviani:

The first premiere of the Wuppertal Tanztheater was a three-part evening - as many city theater companies do: Fritz by Pina Bausch, Rodeo and the Green Table. What role did you dance in the Green Table?

Ed Kortlandt:

Pina's first evening was with Fritz, Green Table and Rodeo by Agnes de Mille - and I had the role of one of the soldiers in Green Table...I don't remember exactly which one.

Ricardo Viviani:

Have you ever rehearsed directly under Kurt Jooss - do you have any memories of it?

Ed Kortlandt:

Kurt Jooss came after his daughter Anna Markard had rehearsed the piece - to refine it further. He was already older at the time, but he still showed us how to do it a bit and during one rehearsal he suddenly said, oh, I have a bit of muscle ache! We thought, man, who doesn't have that? He also told me that I should take off my glasses, it would interfere with the expression! Later under Pina, I danced Kontakthof with glasses on. I also spoke briefly with him about his decision to leave Nazi Germany. He gave me a lot of inspiration - rather than just correcting the foot positions, which was already done. The piece Rodeo by Agnes de Mille was also well rehearsed by her assistant Vernon Lusby. She came afterwards, she also inspired me more than choreographed me. For example, she spoke about the beginning of the piece: the vastness of the land, and as we stand there and we do something similar, she talked about how to imagine that. There was a different vision of it! And that is incredibly important: a vision when you dance! I have to add something else: Pina worked with different choreographers in America, and she once told me that there was a scene where a dancer was standing there and looking into the wings. The choreographer asked him: What do you see there? The reins, the stage manager? No, no - a tree! What kind of tree? And suddenly he stood completely different - he imagined this tree! And that is essential - that one has an image of what one is doing!

Ricardo Viviani:

Rodeo, Green Table - and then Pina's first big theater piece, Fritz! How was the process? Did she start with something else, researched...?

Ed Kortlandt:

It was all new to us, for me Fritz was just a very small part - and Pina just choreographed it. It was not yet so, that we had a big say in it. That only came later!

Ricardo Viviani:

Which role did you play?

Ed Kortlandt:

My own. Marlis had the role of young Fritz and I was a man-woman or something like that. That was my role, I believe.

Chapter 3.4

FliegenflittchenRicardo Viviani:

Fliegenflittchen was a piece they performed as part of the program with you and Heinz Samm...

Ed Kortlandt:

In the first year we weren't really a "Tanztheater Wuppertal" yet. We were the ballet of the opera. That's why we had to do other things too - operettas for example: Zigeunerbaron, Zwei Kravatten, a musical, and so on. Pina obviously didn't want to do that, so Hans Pop, her assistant at the time, choreographed it. And that was nice - also with the choir and the orchestra and so on - to get to know the other departments right away. Of course, the people who came later didn't have this chance! There was more distance then. But we felt integrated into the big picture of the opera house. We also had a canteen - and after the show we often had a glass there with the singers, things like that. That was very enriching! Besides these things, Pina also did small things - that includes Fliegenflittchen. That was a duet for Heinz Samm and me - and Heinz was the fly and I was the floozy! That was kind of a seductive banter, where we jumped onto a chair and back down and danced around together - you have to see it, I can't explain it! But it was quite inspiring, quite nice! We were also on a guest performance with it in Stuttgart.

Chapter 4.1

IphigenieRicardo Viviani:

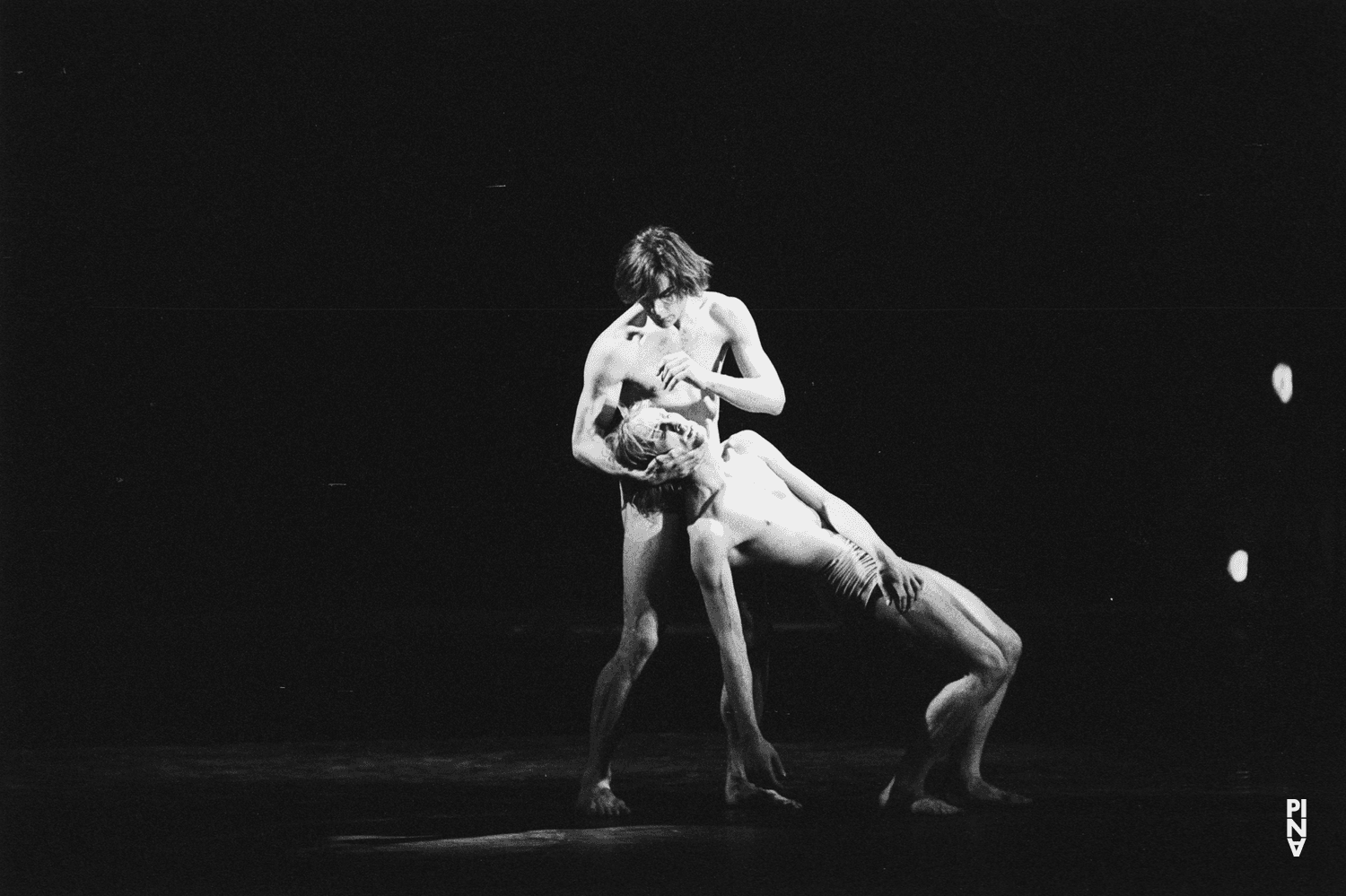

In the first season, a very important piece came - a master work from you: Iphigenie. How was it with Pina's movements and how did it influence the work of the other dancers?

Ed Kortlandt:

When we rehearsed Iphigenie, we worked on the solo roles very closely with Pina. There were many things that Dominique Mercy and I had together. And because we didn't always have access to the ballet studio, we worked on another rehearsal stage. It was a free exchange: Pina gave us movements to try and Dominique and I could always say, oh, let's do it this way instead. That was her choreography, her duet, but it couldn't be any other way, then when two people are supposed to do something together, they have to adapt to each other! Pina was inspired by us in Fritz - so that we should both do it. We have a scene together in Fritz - and Pina already said: Oh, this is really like in Iphigenie, the two men! She saw us in Fritz - because someone else was originally planned for the role, then took on. Someone else was originally planned - that was Heinz Samm! But at some point Heinz said, I don't feel like it anymore, and then he didn't come anymore. Then Dominique and I just kept going, Pina felt a little guilty - and Fliegenflittchen made for Heinz and me. That was the context!

Chapter 4.2

Restaging in the 90sRicardo Viviani:

Iphigenie was on the program for three consecutive seasons. It was a big production with orchestra and music, so it needed a lot of theater personnel. And then it wasn't played for many years! There was a time when you were away from the company for a while, but shortly before that Iphigenie was restaged.

Ed Kortlandt:

In 1990, Iphigenie was restaged and Malou, Dominique and I did it again - the same cast as years before: Carlos Orta who had played Thoas in the first premiere had passed away, Lutz Förster then took over the role. I had resigned, Pina was very clever, also business-wise. I had no experience with the hierarchies in German theaters. In the group in Rotterdam we were all equal. By Martha Graham not everyone earned the same, but there were no hierarchies in the sense of "Solo", "Solo with Group" - I didn't know about that. But in Wuppertal there was: in the ballet, in the opera there were the "group dancers", solo with group and so on. I had a group contract and Malou and Dominique had solo contracts. I said, well, it can't be like this! Then I got a solo contract - and stayed. Two years later I quit again because there was talk of guest choreographers coming. After my experience in Rotterdam, where I had almost stopped dancing, I said, no, not with me! Then I got an exclusive contract with Pina! Two years after I quit again, Pina asked, do you really want to go? I said, I have to get out of here! Because Pina's early pieces like Blaubart and so on - you tear your guts out of your body. I had to get away from there, then Pina gave me half a year off, with salary continuation, I only made the scheduled performances. After that I couldn't say anything anymore ... But then after 18 years with Pina, the call came from Rotterdam and Pina couldn't keep me anymore - I was gone!

Chapter 4.3

Second seasonRicardo Viviani:

In the second season there was the Fünf Lieder von Gustav Mahler and Ich bringe dich um die Ecke… with popular songs, together with Großstadt by Kurt Jooss. Recently I watched Adagio, the Mahler piece. You can see there - as in Fritz - so many elements that we know from Pina: the social relations, but always in motion. Can you remember Adagio?

Chapter 4.5

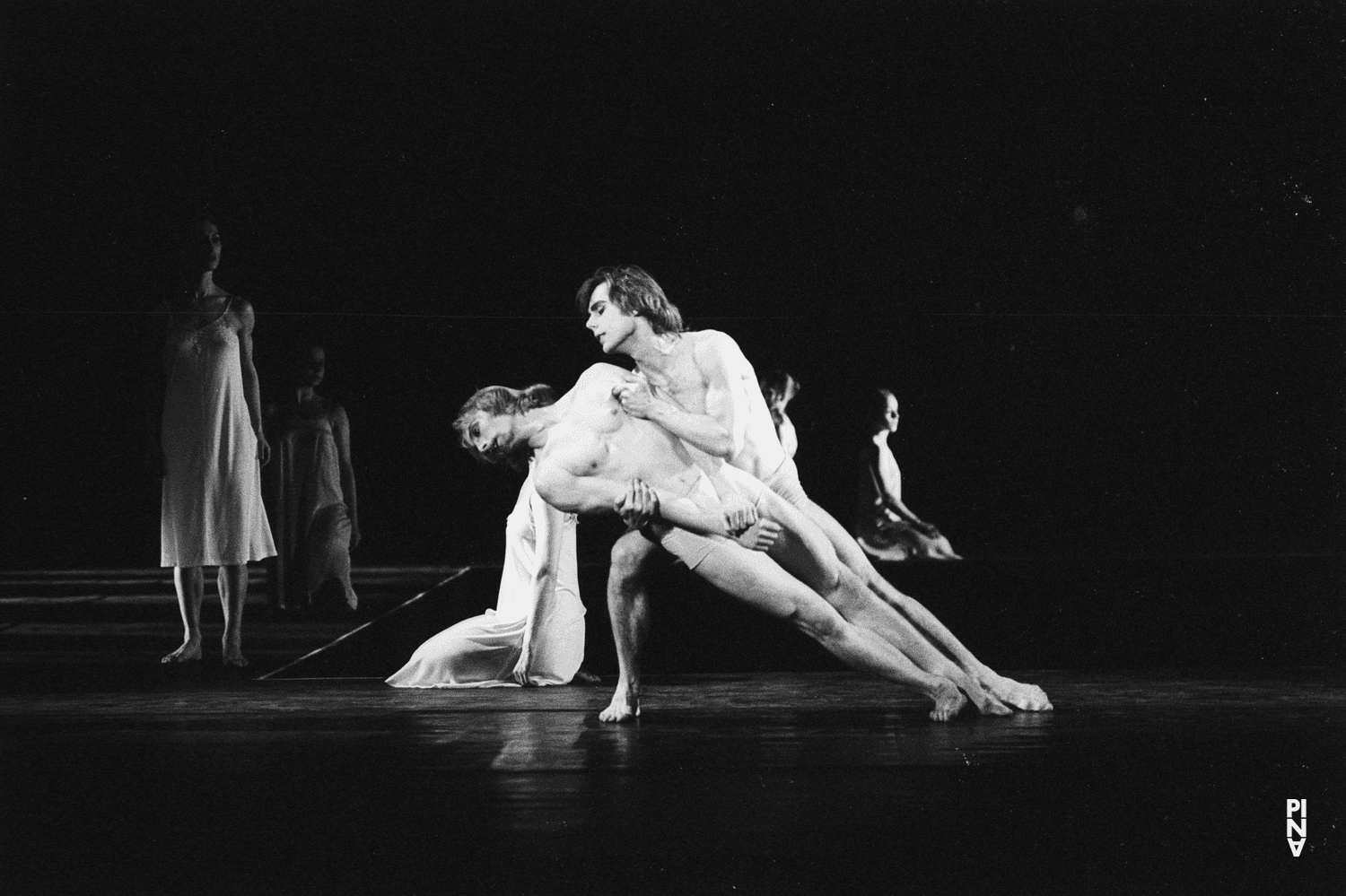

OrpheusEd Kortlandt:

But in the second season we started with Orpheus. Back then, people wondered if it could be similar to Iphigenie, but it turned out completely different. In Orpheus the two main roles - Orpheus and Eurydike - are double casted: a dancer and a singer. The choir was placed on the balconies - because there was no room for the singers in the orchestra pit. Orpheus was played by Dominique - and because he wanted to leave in the next season, she immediately thought we had to have a second cast, so Dominique and I created it together with Pina. Pina then announced two premieres: one with Dominique and Malou and one with Jo Ann Endicott and me. That was a very fruitful collaboration, where Pina also gave movements, and asked us to combine them with our own ideas. So we developed this together.

Chapter 5.1

Work environmentEd Kortlandt:

I was often asked, how did it work out with Dominique and me: it went excellently. Not only that: we were friends all these years until today, that's already 50 years that we have remained close friends. Just recently I visited him, we talked for two hours about this and that. So, what other people often suspected: were there any hostilities between us? No! And that's something that worked out very well between us. Eventually, Pina didn't want this division between solo and group anymore. She thought that all dancers had something of their own, and that's why she wanted to give everyone a solo contract. That expresses the respect Pina had for the individuals. Everyone has their own role and personality and everything they bring is never better than what the other one does. They're just completely different, and that has been one of Pina's best qualities - I wanted to stress it here. That kept the company together. Because it often happened that people came and went - like Dominique and Malou in the third season, Nazareth also left, Héléne also left - and she never said: Ah, if you go, you don't have to come back! She always said, I like the people, too bad they want to leave. But if you want to come back - please do! And I would like to highlight this positive quality of Pina's!

Ricardo Viviani:

In 1980, the different personalities really come to the fore - I saw 1980 back then. In the end, you have the feeling that you know each individual personally! That's amazing and very interesting!

Chapter 5.2

Calling by my nameEd Kortlandt:

In Walzer there is a scene where we all stand in a line to say something: a piece of advice our parents once gave us. We imagine ourselves as one of the parents, and speak to ourselves. Jean Sasportes said: Jean, do what you want – but don't get caught! And Janusz said: Janusz, sleep with socks! And I said: Eddie, my mother always called me Eddie, if you ever have a girlfriend, take a close look at her mother, because your girlfriend will be just like her one day! And that's how you get to know people, when they address themselves by their own name, that throws a little spotlight on someone. We never played roles with other names – we always played ourselves!

Chapter 5.3

Work process in the LichtburgEd Kortlandt:

The Lichtburg, our rehearsal room, was originally a cinema. So, there was no natural light, you didn't know if it was day or night, raining or the sun was shining outside. You couldn't do anything else but to focus on yourself. The way of working developed into Pina asking questions. We all stood in a row, still smoking at that time, and Pina asked a question. You thought about it, what comes to mind, then someone came forward, said or did something that had to do with Pina's question. The questions were always vague, actually they weren't even questions. Often one didn't understand it and the French said, Huh? Qu’est-ce qu‘il a dit? The first stage was confusion! For example, one question was "A Christmas dinner" - actually not a question, but you thought about something related to "Christmas dinner". And then something came to mind, they went forward, did something - and everyone was sitting there, watching. Then the next one came - and everyone wrote it down. And Pina's table was full of paper, she noted everything. Weeks later Pina would come and say, oh, you did this and that back then, let's do it again! Then you looked in your little book what and how you did it, and then you did it with someone else, suddenly a small scene arose. And then another scene, and it was put together, and it became bigger, a block. If something was missing, Pina asked further. Much of it was discarded, slowly it became a whole and until at the end it was all put together.

Ed Kortlandt:

In Bandoneon, it happened once that the part before and after the break were exchanged, and that after the dress rehearsal. It developed out of nothing, there was no story, no music and we made a piece out of it - unlike in the early pieces. There like were seeds that sprouts, or like a fog that rises and you suddenly see the landscape. Pina was always a surprised as well: she might want to make a cheerful piece, butthen another piece emerges out of it! It gets a life of its own, like with writers who write a book and suddenly the characters react differently as expected. The result was that when you saw the piece on stage, it always looked very real! This construct of Pina was brilliant! Very fast and slow, light and dark, quiet and loud, sometimes tranquil, sometimes fast scenes - it was a composition like a symphony, with sequences that carry you away, but all the things you saw were uncovered from the dancers! It was never like Pina ordering: do this and that. The scenes show very personal things from the dancers, they are not playing something - and that's what made Pina's pieces so believable!

Ricardo Viviani:

You have witnessed the development of these processes from the inside. There must have been some organic development - right? Did you ever recognise a turning point when the dancers were developing more and more of their own movements?

Chapter 5.4

Evolution not a revolutionEd Kortlandt:

It is said that Pina revolutionized the world of dance. Of course, this is not the case, she evolved it! She always kept her feet on the ground. The collaboration with the orchestra was initially ok, but at some point it didn't work anymore. When she wanted to do Blaubart, it didn't work, so she had to find something else. She came up the idea that the character Blaubart listens to the music and remembers it. He rewinds the music on stage, so he can revist it. What you see in the piece is the memory of Blaubart! It was actually planned with the orchestra, but it did not work. The next thing was that she was invited to Bochum to work with the actors there, of course she couldn't rehearse any movements with them, so she had to do something else. She asked tem: You are sad, how are you sad? Play "sad". And then the actors did something that was sad. Slowly it settled in: six times "waiting", six times "angry", six times this or that. There were different versions of how to greet each other, or be sad, or something like that. That was the core of their work. With us dancers, it gradually settled in with the questions. In practice, it happens that sometimes nothing comes to mind, on other days the ideas are bubbling. That also applies to impulses from the colleagues: someone comes forward, does something and you think, hm...Then you see something, and suddenly an idea comes to you that sprang out of it. Then you do it, and so you have an inner connection to the whole thing, all depending on the sensibility in that day.

Ricardo Viviani:

That was already special - to create this environment where people feel secure to dare to do silly things. Things that you may think to yourself: Oh, that's nothing...

Chapter 5.5

In the last minuteEd Kortlandt:

In this way of working, answering questions, one sometimes naturally comes up with the biggest nonsense. And the great thing about Pina was: You could do what you wanted! If you thought it wouldn't work, but you did it anyway - she never reacted directly! If it was something funny, she sometimes laughed. But that doesn't mean she liked it. And whether she liked it or not - she noted everything and then later it was also in the context with the others, whether something was good or not. And the music was also chosen like this. In this process you can't say from the beginning that the music should be like this and the stage like that. Rather, these are things that often arise at the last moment. Sometimes it doesn't fit - she wanted to use Elvis Presley's music, Only you, but unfortunately that didn't work in the piece, but it did in the next piece „Nur du“! And it was the same with the stage. And the stage designer Peter Pabst was always desperate - because he couldn't plan it in advance like it is in the movies or in the theater: The stage design is first planned, then a model is made and inspected, then it goes to the workshop and so on. No, it was done the same way - sometimes at the last moment, in the last two weeks, the whole stage design had to be made suddenly! This drove everyone crazy!

Ed Kortlandt:

Sometimes the stage wasn't ready: for example, in Keuschheitslegende there were supposed to be five crocodiles - but at the premiere there was only one! And after the premiere the workshop said, yes, the premiere is over! Finished! And Pina had to fight hard to get the other four crocodiles made, damn it! And when the first crocodile was ready on the stage, one had to crawl backwards into it and another had to hold its mouth open, which couldn't be done alone. And he had a walkie-talkie, which didn't work at first, and a small fan so he could get enough air - and he was in this small crocodile interior, crawling around the stage. And at the very first rehearsal, the guy was in there and one was backstage and we were in front because Pina was explaining something. And the animal wasn't quite dry yet, the smells of the paint had made him a bit dizzy and he got panic and tried to crawl out of there - which didn't work - and he had to go to the hospital! But the next day he went back in again.

Chapter 5.6

I am making DANCING difficultEd Kortlandt:

Then we had rehearsals for Palermo, Palermo. These pieces, collaborations with other countries, were always created by us spending a few weeks in the other country to be inspired and then make a piece about it. That was the case with Palermo. We were in Palermo for a few weeks and rehearsed in a small theater. One time during the rehearsal we were literally attacked: several men in black suits suddenly came through different doors and I thought, what is this? That was the mayor, Luca Orlando, who fought against the mafia and commissioned Pina with the piece because he was very culturally engaged. He also commissioned films against the mafia - a very interesting man who never announced when he was going anywhere because he was always in danger! He suddenly came by to see what we were doing and then he was gone again. And another time there was a huge crash on the backstage and we thought the whole house was going to collapse! That was Peter Pabst, who had tried out a stage design. He had taken stones with him - because in Palermo there were so many buildings that hadn't been finished, because the mafia was making money from it and so on. And then he got the idea to take crumbled stones and build a small wall of stones - and he had dropped it without warning us! That was like a raid! And that then came into the play. When you see Palermo, the curtain is only down - which is usually not the case in Pina's plays. And when the curtain goes up, the light goes on and you see this wall and think, what is this here? And gradually the wall collapses backwards and breaks into a thousand pieces with a loud noise! When we did this for the first time at a rehearsal, it damaged the floor so much that you had to support it with rods underneath. And then for the performances they always put an extra thick wooden floor on the theater floor to withstand the impact of the stones! And then it wasn't so easy to make it all run smoothly. If this is the stage and here is the audience and here is the wall, then of course the wall should fall in the right direction. But who can predict that it won't fall like that? So everything had to be secured and it was like this: there were four ropes made of a different material at the top and bottom and they were attached very precisely so that the wall would fall in the right direction! "I make walking and dancing difficult" – and how!

Ed Kortlandt:

Something similar happened with Sacre du Printemps. The idea was that it should be played on peat. And at the first rehearsal it was dusty and we were all coughing - so it had to be made wet. But then we all slipped and fell! Then there were also dancers who said, this doesn't work, I won't do it! But there was a rehearsal where it was decided, we do it - or not. And - what a coincidence: Nobody had to cough, the moisture was such that it held and nothing was dusty! Afterwards it was not always good, but then we found out how to do it: There was this big container, as big as a garbage can, the peat went in there, then the day before a certain amount of water was poured in. And then we eventually found out how much water was needed for the peat to have the right consistency!

Ed Kortlandt:

Of course! We were friends - through photography too. And he was Dutch, so we always spoke Dutch! And I knew him very well. We both photographed as a hobby. And I was also allowed to use his darkroom. And Rolf and Pina, Tjitske and I, Malou and Dominique were even closer friends. And we also went on vacation together - we were at Malou's parents' house, in their big house near Marseille. So we also went on vacation together, drank Pastis! It was a close affair - both professionally and privately!

Ricardo Viviani:

Rolf has been making interior rooms from the beginning and introducing everyday clothes as costumes! Already in Iphigenie there were these special rooms - do you remember?

Chapter 6.2

"We've never done that"Ed Kortlandt:

At the beginning, Pina had different stage designers. Actually, Hanna Jordan was planned for it, who was a stage designer in Wuppertal and worked with Horres and guests - a very renowned stage and costume designer. And she also had lively conversations with Pina - but somehow it didn't work out with the two of them! And Rolf Borzik had actually studied graphics at the Essen Folkwang University - that's where the two of them got to know each other. And he always had a great influence on her and at some point Pina said that he should take a look at stage design. And that was difficult for him in a way, because as a stage designer you not only have to draw the stage designs and have ideas, but also have to make sure that they work in practice! And for that, craftsmanship is also very important! And even if you can do it in principle, there are also theater craftsmen who have their own ideas and visions - and when a newcomer comes, that is always difficult! Pina experienced this herself - she wanted this and that and then it was said, ah, that's not possible, we've never done that before! We heard such sentences often! When Pina wanted to make Arien and flood the entire stage, it was also said: Ah, that's not possible at all! Iphigenie was then the first play she made with Rolf. And afterwards Orpheus. And he worked himself in very well and Pina and he also fertilized each other! Rolf then drew the costumes and then of course there were experts in the costume department who could then implement what the two could not. That worked out well!

Chapter 6.3

The Seven Deadly SinsRicardo Viviani:

He did a lot of research. For example, for Todsünden he has an imprint of a street...?

Ed Kortlandt:

Rolf Borzik and Pina were very detail-oriented and wanted it to be exactly as they wanted and no other way! And Todsünde is a piece that takes place in the gutter! And he wanted to have the gutter on the stage! And the wooden or linoleum floor that you have in the theater obviously doesn't work there! And he then actually went with people from the theater to a street – and he put that floor on the stage! And we men had to dance around on that stuff in the second half of Todsünde as women in high heels! I made the dancing difficult – that could be said outloud here! But that was of course really somehow and with Todsünde, which takes place in the gutter, Rolf also thought about the lighting! And so the stage was eventually immersed in cold neon light – that also belonged to the atmosphere of a gutter.

Chapter 6.4

HOW they move and WHYEd Kortlandt:

Pina was very detail-oriented. And I would like to briefly correct something that is sometimes incorrectly quoted: Pina Bausch was not interested in how people move, but in what moves them! I first read that from Jochen Schmidt back then. And Anne Linsel also used it in her book later, you often hear that. And it's all wrong from front to back! Pina was someone who could spend two hours tinkering with the first ten minutes of Sacre – and work on the same spot again in the evening! If you want to express something and you express it through dance, through movements – of course she was interested in what moves people, her entire body of work shows that – but if you want to show something, it must be precise! And if you want to express something through movements, you are interested in how people move! So one could say: She was interested in how people move – but above all: What moves them! That would be the right quote here!

Chapter 7.1

When the title comes, it is readyRicardo Viviani:

The Tanztheater has a long tradition of restaging and maintaining the pieces. And the roles are sometimes distributed. Here, the form also plays an important role.

Ed Kortlandt:

Sometimes the new pieces were not yet finished for the premiere - then they were called Dance Evening I or Dance Evening II, there was no real title yet. Also, because they were still working on the process! And sometimes something was changed after the premiere - but then the title came on top and then it was finished and no longer changed! And if we now take up an old piece again after decades, we look at the old pictures - all pieces were filmed! And then we look at the old films and that is then just like a painting - you don't change anything there either! You don't say, this Rembrandt is not modern enough, we have to change something! And that is also our main concern with Pina's pieces, to make it exactly as it was back then - like a painting, finished! Once there was a major change - that was with the piece Carnations, which was actually planned with a break. And there were so many scenes, it was a bit too long! She had found Kontakthof too long as well, but didn't know where to cut it. But with Nelken she found a way and made a version without a break - and that's how the play is still performed today!

Chapter 7.2

Focus: Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

Café Müller - it was a crazy season back then, when they made three pieces: two in Wuppertal and one in Bochum. And that's when the concept of Café Müller with four choreographers was created! Pina plus three more. Gerhard Bohner, Gigi Caciuléanu, Hans Pop - and Pina Bausch. And they all had a concept - can you still remember the genesis of developing the same parameters?

Ed Kortlandt:

It should have been the same room and be called Café Müller. And they did very different things - and it was an exception for Pina that she only did something short and then let three others do it. She never did that again later. And I don't know if that was such a good idea. But maybe she also needed a break and wanted to do something small. The Strawinsky evening originally consisted of Cantata [Wind from West] and Der zweite Frühling - that was a tango by Strawinsky - and Sacre du printemps. And later the first two pieces were taken out and then we only played Café Müller and Sacre and combined them. But the pieces of the other three choreographers were not shown after the season.

Chapter 7.3

The piece 1980Ricardo Viviani:

In 1980, Rolf passed away and then the piece 1980 was created - do you still have memories of this time?

Ed Kortlandt:

In 1979, Rolf became ill and his last stage design was for the last piece Keuschheitslegende. After he passed away, Pina created the piece 1980. Pina said she had to make it, because she could not just stay in mourning and do nothing. When you watch the piece, there are many things that have to do with the beginning and the end of life - certain rituals that exist in life: birthdays, etc. It also has a sad element to it, but it is more hidden. It depends on the audience if they even notice it. For example, when 1980 was shown in Los Angeles - people there are used to being entertained. There is a scene where someone says: “I had a little party - just I, myself and me” and then they tell “The cake came to me and she ate all the pie and served the tea to me” - so it is actually a very onely affair! Someone drinking tea alone and celebrating their birthday! And the Americans were laughing so hard - that's funny! They didn't understand that! And Pina's pieces are so versatile: What you see, you know from your own experience! Some things are also hidden, you don't see them directly. There was once a scene in a piece - I don't remember which one it was: Marion and Pina were sitting together and Marion said to Pina: But the little thing there, people don't even see that! And Pina said: That's for the initiated! And if you see a piece again and again - depending also on your own experiences and your own mood - you always discover new things!

Chapter 7.4

Restaging Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

Shortly after the 1980 premiere, "Café Müller" was revived and performed in Nancy. Then came the South America tour: Did you play in "Café Müller" - or did you play there at all?

Ed Kortlandt:

Café Müller was originally made with Pina herself, Malou and Dominique, Jan Minarik and Meryl Tankard. And there was Rolf Borzik who cleared away the chairs scattered around for the protagonists to act! And when Rolf died, that changed - Jean Sasportes took over the role. And Pina, Malou and Meryl...Meryl's role was later taken over by Nazareth. And at some point I took over Jan's part. But I think that was because Jan had some health problems. So I actually stepped in for him, but then I danced it more often. But I think Jan danced it again too. But I don't remember if it was in South America.

Chapter 8.1

The world of a dancerRicardo Viviani:

In the pieces of dance theater there are always references to classical dance: sometimes a "plié", sometimes a "tendu", sometimes a big "manège" or an "entrechat-six". Where does this come from? Does it come from the world of dancers, what they bring into the pieces - or is it intended as a comment on dancing...?

Ed Kortlandt:

If Pina made a piece, as I described it - if people had to go forward to do something - then they often also did something they had learned in ballet class! And you could also distort it or do something completely different with it. But that it keeps coming up again and again belongs to the dancers life - you can't get around it!

Chapter 8.2

What is dancingRicardo Viviani:

At Dominique's, these "entrechat-six" were interpreted in Carnations as a comment on the dance that Pina did not do. But of course that has been transferred to the viewer...

Ed Kortlandt:

One has to think about what dancing actually is! And when someone moves, you can already see that there might be something dance-like in it. And in a tango hardly any dancing is actually done! And one can already say, depending on how it is done, if something was danced or not. And there was a time when Pina used little dance. For example, there is the piece Walzer, a long piece - I believe her longest piece, four hours long! And the premiere was in Amsterdam in the "Theater Carré". And the Theater Carré was originally a circus, with an arena and a steeply rising audience area. That's why Pina also tried to do things lying on the ground - so that you could see it well from above. And in Walzer very little is danced! But at some point the audience wanted to see dancing and someone shouted loudly "Dance, Dance!" - as a demand. And it just happened to be at the scene where Beatrice stands up and just does a little something with her shoulder and counts "Jeté" ... - so all these dance terms. And she does something with her shoulder but only internally, without actually doing it! And that fit perfectly after this comment from the audience!

Chapter 8.3

Viktor victoryEd Kortlandt:

Then we made the piece called Viktor: It can be the name of someone, it can also mean overcoming and "winning" or something like that - doing something impossible! And this was the first piece we made in collaboration with another country - in this case Italy. We went to Rome and what came out of it was that the piece takes place in a grave! In Rome we visited the catacombs and that's where the macabre in the piece came from. And we picked it up in the set design, which consists of a large grave. And there is someone up there, Jan Minarik, who keeps shoveling more and more dirt. It would surely take years to fill it! And the piece starts with a scene in which something happens that is actually impossible. And that came from the fact that we had a pre-dance in New York. Someone came to pre-dance who had no arms! That was a ... (Contergan-victim) a young man who had no arms but was dressed in bright colors. He was able to "chassé" and do other things perfectly with his legs! This inspired Pina in the play "Viktor": Anne Martin comes forward in a red dress, very elegant - and without arms! She stands there confidently without arms and smiles at the audience. Then Dominique comes with a fur coat and hangs it over her, so you can't see her lack of arms anymore and she walks off elegantly and Dominique follows politely - that was the scene. This was all inspired by the young man who had danced in New York! And the play continues: The people no longer live in the grave - but they dance!

Chapter 8.4

Auf dem Gebirge hat man ein Geschrei gehörtRicardo Viviani:

Do you still remember Gebirge...?

Ed Kortlandt:

There are a few pieces of Pina's that really challenge the audience when they see them. Especially in the early days with the company, the local audience really liked the beautiful classical ballet! And then Pina came with Agnes de Mille's Rodeo and The Green Table, then Iphigenie and Orpheus - those were pieces...the third act of Orpheus is actually like classical ballet! You can also look at Swan Lake - and Pina's Orpheus is still better, I'd say: The most beautiful thing she ever did to music! But the other pieces of Pina were a bit tricky - Bluebeard and Mountains for example. And that was the time when the audience had a lot of trouble with this new form of dance. There were also aggressive outbursts in the audience, the spectators partly booed and ran out of the room slamming the doors. That was difficult! Macbeth was also such a transitional piece, which the audience reacted very strongly to in the premiere!

Ed Kortlandt:

Gebirge was such a piece: It starts totally absurdly with Jan Minarik wearing a red slip, with a boxer's nose - red glasses and a red cap - practically naked running across a raked landscape of black earth. The stage is slightly tilted. And then there is a grand piano - and the whole thing looks very surrealistic, unreal! And there are some wonderful scenes in it - for example a scene with Lutz and Dominique, in which Lutz looks completely lost and has to hold on to something. And then he stands there - and when he lets go to go somewhere else, Dominique tries to accompany him and help him. And you don't know what it means, but you have to hold on, take a deep breath - and then it goes on! But if you let go, you're lost! And it was a piece with a twenty-minute break - and Beatrice stands on the stage the whole time during the break, stands there and eventually has to really cry! The things with Pina are real, they're not just playing it! And that's all very touching - also with this music: It comes from Heinrich Schütz from the time of the Thirty Years War. Then you have these associations right away! The title of the music is Auf dem Gebirge hat man ein Geschrei gehöret - that's the Thirty Years War! But if you see such a piece after a busy day, after you wanted to relax and you expected a beautiful classical ballet where the fairies are all jumping around and turning pirouettes, you can understand that it was a bit difficult for some people! Absolutely! These are my memories of Gebirge, because it was also one of Pina's harder pieces, I would say.

Chapter 9.1

Back in RotterdamRicardo Viviani:

Then you went to Rotterdam for a little while, away from the company: How long did that last?

Ed Kortlandt:

I was eventually called by the music conservatory in Rotterdam - which is for music and theater and dance was part of the theater department. And this is an institute that was founded before the war by Corrie Hartong. After the war it was linked to the conservatory and later it became the university for music and dance. And Corrie Hartong wanted to make dance known in the Netherlands and therefore offered training so that people could learn to dance and also teach dancing. This was the basis of this academy. And then others came who led it - among others Lucas Hoving. He was also in the time when I was in the small company, director of the dance academy. And at the time when I was called after 18 years in Pinas Dance Theater, an interim director had been appointed - someone who was not from the dance world. That's why they were looking for someone new who came from the dance world. And the founder, Corrie Hartong, mentioned my name - and so this man and his wife came to Wuppertal to meet me. It was in winter and he came alone at first to talk to me and then he said, yes, my wife is outside. In the cold?, I said. Bring her in! Then I served them spaghetti and red wine, then they drove away and shortly afterwards I was invited to Rotterdam for an interview. I had to travel to Rotterdam twice - also to talk to the supervisory board and representatives from the academy. This had to remain secret because other people were also applying for the position. And then I finally became director of the Dance Academy in Rotterdam - the first and oldest training center for aspiring professional dancers in the Netherlands! And at the time I wanted to change something, because when I came, dancing was already known everywhere - you didn't have to train someone to teach it, it was already known through the media, there were already several large and small dance companies. And I wanted to change something: Less pedagogy and more depth in dance training. There were 50 full-time teachers and 20 musicians there and about 600 students and students - so a big institute. And I got so much resistance from the people who wanted everything to continue as before - and I couldn't prevail in the end. So I said: Then do what you want, bye - and then I left again. Then Pina heard that I was free again and in the meantime I had taught everywhere - also in Lausanne with Béjart or in Bogotá, Paris and Amsterdam - and then Pina asked me if I wanted to be her assistant. That was in the spring of 1994 and from then on I was responsible for the training, had to lead rehearsals, hold hands - all that belongs to it- I had to be there earlier than Pina of course, and leave after Pina, which wasn't easy because she was there all the time! And if I gave training at 10am and she only came at 12pm, I was already a bit tired, then there were rehearsals, meetings in the afternoon and in the evening we have rehearsals again. And around 10.30pm when I had pushed everyone out of the Lichtburg and waited with Pina for a taxi and made a joke - then the day was over. And then the next day came! That was of course a pretty exhausting time for me - but not unsatisfying!

Ricardo Viviani:

How does your lesson look like? Do you do modern, and ballet sometimes - what is it like?

Chapter 9.2

Preparing the dancers to danceEd Kortlandt:

I have a classical training, based also on folklore, without a degree. And with Martha I did Graham. And in Wuppertal I then learned the Folkwang technique. There was Hans Züllig, one of Pina's teachers. And Hans Züllig made a mix -unlike Martha, where everything is new, on the ground,, but standing, on the barre, like in classical ballet, with similar exercises too, but much with the upper body and arms. Much more flexible than classical ballet, which is actually quite static from the body. And we were in Paris - I already had my contract for Rotterdam - we were there for a guest performance in Paris. And Hans Züllig gave the morning training there, in the afternoon I drove with him somewhere else, where he also gave training. And then I wrote down everything in shorthand that he did and said. After that I worked out everything in my hotel room, so that I was able to read all of this correctly and in the evening I danced my interpretations. Intensely, for two weeks. After the two weeks I was with Hans Züllig for a few hours in the dome, in Theatre la Ville - there I showed him again for safety everything I had written down, his movements and remarks etc. And he approved it. And that was the basis of my training! But over time exercises were added, which I had thought up myself and elements from Pina's pieces, which I then also used. But at the barre I do a mix of classical and modern at the beginning: one exercise is classical, the next modern. And in the center I only do modern technique, which of course can also be done both ways . And my training is focused on dancing - unlike Hans Züllig or the people whose classes I once observed. There was actually no one who did it like me. I think you have to come to dance! When I prepare it in my head, I have a certain combination that I want to make at the end - and the preparation starts at the bar! I do exercises that later flow into the final exercise I make. And in between I do a little phase with this and that exercise and, wonder of wonders, in the end all exercises are elements in the final exercise! So the dancers have the feeling that they already know everything - and are free to dance and go away satisfied and come back the next day! That's how I did it!

Chapter 10.1

New York inspirationsRicardo Viviani:

Pina made various friendships during her time in New York when she was a student, with people who were very important to her. Later, her company performed again and again in New York. Arien and the water shortage - can you remember the first performance in 1984 in New York?

Ed Kortlandt:

When we played Arien in New York, we had the problem that the water wasn't warm enough. That was always the problem in Arien - because the water is only about 4 centimeters high in the pool where the hippopotamus goes in later. And this 4 centimeters of water at the beginning have to be very hot so that it is still reasonably warm after half an hour or an hour! But in New York it was already too cold at the beginning! And we - also Pina - said: That won't do. And then they fiddled around with the heating, probably an hour and a half or so. And Andy Warhol was at the performance, sat there in the first row, waited patiently - while many others were walking around and talking. But he sat there and waited. And the director of the theater got his hands dirty in the basement to change something in the pipes so that the water got hotter. And that took some time. He had his tuxedo on for the premiere - and was tinkering around! And then Urs Kaufmann recorded it in a scene in Viktor! In the play there is a scene where you can see the stage from the audience on the left - he set up an electric saw and a wooden board there. And then - dressed very smartly in black, with fine manners - he sawed the board! The combination of the craftsmanship and this fine outfit goes back to the director of the New York theater - Harvey Lichtenstein.

Chapter 10.2

Arien and the hippoEd Kortlandt:

While we're talking about Arien: At the premiere, there was this hippo. And it was like with the crocodiles - people had to crawl in backwards. And the back person then climbed into the back legs, the front one into the front legs. And then they were in this thing and could sit down, stand up and go. But that was a pretty heavy thing! And the idea was that the hippo would stomp around in the water and also dive deep into the pool to bathe! And at the beginning you couldn't get out of it anymore! And through the heat the material became limp. And if you imagine the two people in it and the back part gets more and more limp and they can't get out of the water anymore... And even at the premiere Hans Pop had to pull on the animal to get it out of the water at all! But that was only later - because at the time of the premiere the hippo was not yet finished. This means that our dancer Hans-Dieter Knebel, who was an outstanding interpreter, took on the role of the hippopotamus. And it was planned that the hippopotamus would move very slowly and stand there at the end, and the protagonist would be his lover, and they would go here and there and also into the water and out again - and I thought we never had a better hippopotamus! He did it so excellently - the charisma of the man is really incredible! But with the hippopotamus there was this difficulty with the heat, the limpness and not being able to get out of the water. And this is still the case today during performances: I also instructed the people as an assistant with the walkie-talkie - "now to the right, now straight ahead, stop! Sit down!" (mimics). And when I said "Stand up! This means that our dancer Hans-Dieter Knebel, who was an outstanding interpreter, took on the role of the hippopotamus. And it was planned that the hippopotamus would move very slowly and stand there at the end, and the protagonist would be the hippopotamus, it was almost her lover, and they would go here and there and also into the water and out again - and I thought we never had a better hippopotamus! He did it so excellently - the charisma of the man is really incredible! But with the hippopotamus there was this difficulty with the heat, the limpness and not being able to get out of the water. And this is still the case today during performances: I also instructed the people as an assistant with the walkie-talkie - "now to the right, now straight ahead, stop! Sit down!" (mimics). And when I said "Stand up! Now turn left up front!"...that was so funny! And as long as the walkie-talkie worked, it worked - but when it ever failed...oh no!

Chapter 10.3

Pina Bausch dancingRicardo Viviani:

Then let's talk about the two pieces in which Pina dances herself. How do you remember her dancing in Café Müller and Danzón?

Ed Kortlandt:

Pina once told me something very interesting about Café Müller: She has her eyes closed when she walks around and bumps into the wall. She said that one time something wasn't quite right, but she couldn't explain what it was. Eventually she figured out that it makes a difference if you look with your eyes closed down or straight ahead when walking.Because she had looked down with her eyes closed instead of forward, something was off for her. That shows how much depends on these tiny little things! And in Danzón, where she also dances - I don't know if it meant anything - but at the end she goes away and waves to the audience. It was almost like a goodbye!

Chapter 11.1

Tanztheater in your lifeRicardo Viviani:

What is Tanztheater? How important is it in your life - or for the world?

Ed Kortlandt:

After 50 years of dance theater, it has become a very big part of my life - and still is! At the same time, it is almost over for me. I am part of Pina Bausch's legacy - and what follows will be shaped the next generation. That is their life now! I belong to a past, I am now the dinosaur in the company - and that is okay too. I don't make big thoughts about how it goes on. That is now in other hands!

I must say, however, that if you look at Pina's work, it has a lot to do with integration: with many nationalities, many possibilities in life, many cultures! And that is the opposite of deportations! And it is important to point this out in these times - because there are many people who believe that they can save themselves through deportations, but that is not the case! Pina's work is to emphasize the humanity - and integration is totally important! I find many cultures manifesting in her work and many nationalities in her company - and that is the opposite of isolation, which is, unfortunately, what one sees today in different nations!

Suggested

Legal notice

All contents of this website are protected by copyright. Any use without the prior written consent of the respective copyright holder is not permitted and may be subject to legal prosecution. Please use our contact form for usage requests.

If, despite extensive research, a copyright holder of the source material used here has not been identified and permission for publication has not been requested, please inform us in writing.